Former mayor Rusdy Mastura remains lost in thought about the great loss of human lives — 2,000 deaths and 5,000 missing souls — in the wake of the Sept. 28 quake in Central Sulawesi that devastated what was his area of jurisdiction, Palu.

By: Ruslan Sangadji

The Jakarta Post/Palu

His biggest lament was that local authorities did not take seriously a contingency plan his administration created in 2012 in anticipation of a major earthquake that could have struck Palu at any time, knowing that the beach-front city of 367,500 people sits on an active 500-kilometer fault line stretching from Palu Bay in the north to Bone Bay in the south.

Called “Skenario 2012”, the document details what the city should do if a magnitude-7.4 quake shakes the robust town. The scenario is about a massive tsunami able to destroy the city’s iconic Yellow Bridge, hotels and shopping malls close to the beach and advises what the town should do when the disaster comes.

“Our scenario matches what happened on the evening of Sept. 28, except that the quake occurred at 6 p.m. instead of 2 a.m. as we imagined in the contingency plan,” says Rusdy, who was in office from 2005 to 2010.

“The government ignored the contingency plan we made and when the disaster did strike, they didn’t know what to do.” The local administration was paralyzed for a week in the wake of the tragedy that destroyed local infrastructure, including telecommunications.

Major quakes in Central Sulawesi have been well documented. Dutch scientists recorded a magnitude-7 earthquake in 1909 that destroyed whole villages. On Dec. 1, 1927, an earthquake measuring 6.5 on the Richter scale triggered a 15-meter high tsunami in Palu Bay, wrecking destruction in Palu and neighboring Sigi.

Among the largest quakes was a magnitude 7.6 in Parigi that sparked a 4-m tsunami in Palu Bay in 1938. A 10-m tsunami swept the coast of Donggala following a magnitude-6 earthquake off Tambu that claimed 200 lives in 1968.

Had the incumbent Palu Mayor Hidayat and Central Sulawesi Governor Longki Djanggola followed the contingency plans as part of their mitigation measures, the loss of life could have been less. The Jakarta Post also found that top local government officials had disregarded the findings about the menace of the Palu-Koro fault line that a team of geolo-gists presented to them in July.

Longki has acknowledged he had received similar warnings from previous studies, but as “nothing happened” in Palu he regarded the latest scientific report as merely routine. So did Hidayat, who famously said that because the Meteorology, Climatology and Geophysics Agency (BMKG) was no God, people did not have to heed it when it advised that the public stay away from the beaches in the event of an earthquake.

The sandy Talise beaches are a highly popular hangout area where commercial buildings of all sorts fight for space.

Liquefaction

The disaster, which invoked international sympathy, has awakened local government authorities from their ignorance about the need for taking scientific advice into account when building residences and vital installations. They are consulting the Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI) and the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) over reconstruction.

Preliminary studies have found that the latest quake has reshaped Palu geomorphologically. Some residential areas have become swamps again and many of the sandy beaches have sunk because of liquefaction. In Kampung Muara village in Donggala, 38 houses sank into the sea.

Forty-one were killed and 12 missing, presumably dead.

Surface ruptures along a 40-km road connecting Palu in the north and Sigi in the south that has destroyed houses and buildings on both sides mark the dreaded Palu- Koro fault line underneath. Researchers from the Center for National Earthquake Studies (Pusgen), Mudrik Rahmawan Daryono and Danny Hilman Natawidjaja, found surface ruptures elsewhere that spanned 70 km combined. Besides, the quake also set off 80 km of seabed ruptures.

“This lateral rupture marks the active fault line. When another quake happens, the same areas will be destroyed again,” Danny says.

Scientists also found landslides on the hills around Palu Bay, land sinking into the sea and traces of massive seabed subsidence they think triggered the tsunami in the bay area.

LIPI scientists counted seven sites of undersea subsidence. A seaside village, Kampung Muara, which was built on reclaimed land in Donggala, went down to the bottom of the bay along with a swathe of land in its neighborhood.

At the famed Talise Beach, erosion by the tsunami exposed what appears to be the remains of a port from the Dutch colonial era. The abandoned port was reclaimed as a road in the 1980s. Iron beams protrude from the sea at the end of the cut-off street.

In the general area, LIPI researchers found evidence that suggests the September tsunami was at least the fifth to have swept Palu.

“It’s possible that deeper excavations would lead to more evidence about other tsunami that had occurred before the five we know,” says Purna S. Putra, a LIPI researcher on geology and paleotsunami.

As for liquefaction, little scientific evidence is available to prove if the natural phenomena had happened in the distant past, but in their folklore the indigenous Kaili people tell of land sinking into black mud, which may refer to liquefaction, the kind of disaster people witnessed in horror in September.

It struck the densely populated villages of Balaroa and Petobo the worst. Official records give chilling accounts of liquefaction. In Balaroa, liquefaction swallowed 1,375 buildings in a 40-hectare area. In Petobo, 2,050 buildings on 180 ha sank into the ground. In Jono Oge and Sibalaya, the specter destroyed 600 buildings and turned 250 ha of residential areas into swamps.

Referring to Dutch ethnographer and missionary Albertus Christiaan Kruyt who researched the area in 1919, scientists figured out the liquefactions happened in former river basins, many of which had been unsuspectingly developed as residential areas since the 1970s as Palu transformed from a backwater town into a bustling modern city.

“[Until the 1970s] people would avoid the [river basin] areas because they knew the land was dangerous [to build on],” says Alimuddin Rauf, a community elder in Palu.

New Palu

The natural disaster has dealt a hard blow to the local economy, too. While the local administration with the help of international community is readying for a multi-million-dollar reconstruction effort, it is still counting the cost.

The Provincial Development Planning Agency (Bappeda) reckons the economy would need at least three years to return to normal. The quake has exacerbated poverty with another 18,400 people becoming poor, making the number of people living under the poverty line in the province 439,000.

Currently, 79,000 earthquake survivors live in shelters. The construction of temporary, more decent houses is about to start for the first 1,200 families. The government intends to share the financial burden with the private sector and state-owned enterprises.

State construction companies Bina Marga and Cipta Karya have pledged assistance worth Rp 1.2 trillion (US$83.90 million) and Rp 1.6 trillion respectively.

Public Works and Housing Minister Basuki Hadimuljono estimates the reconstruction projects would need up to Rp 6 trillion. The final calculation is expected to come by the end of the year along with the master plan.

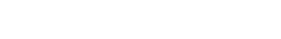

On scientists’ advice, the central government is mulling over a plan to relocate people from disaster-prone areas, mostly those close to the coastlines, which suffered the most because of the September quake. Building in places affected by tsunami and liquefaction is strictly forbidden.

State land in Palu’s eastern outskirt of Duyu, Tondo in the south and Pambewe in the Sigi regency have been designated as most viable substitute residential sites, dubbed New Palu. The blueprint is being finalized by the National Development Planning Board (Bappenas) and the BMKG, with assistance from geologists.

The projects will commence next year and be completed by the end of 2020. Until then, survivors will have to make do with rudimentary shelters.

In Donggala, a tale

of a sunken kampung

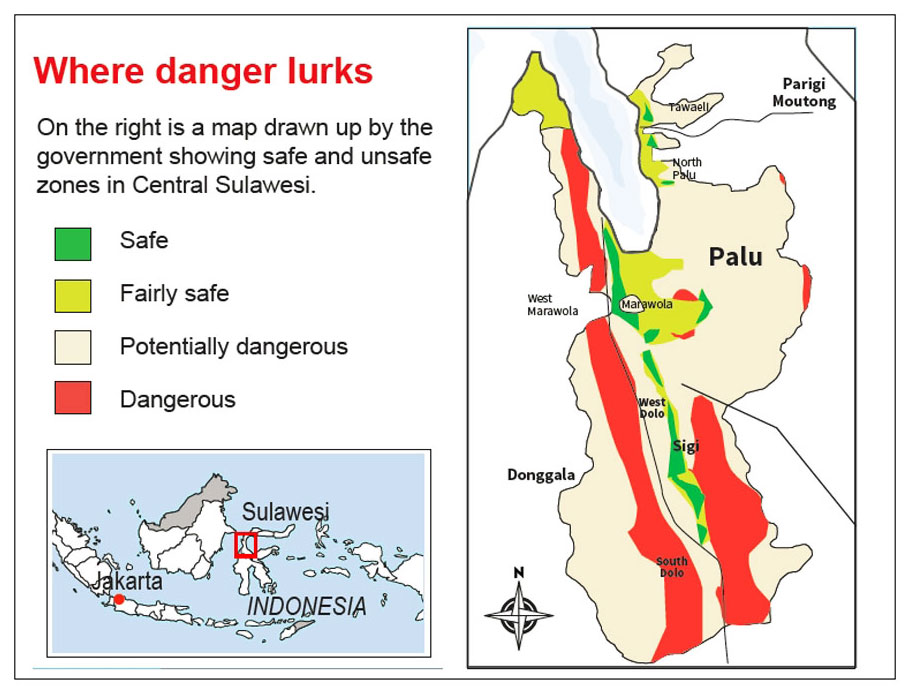

Not forgotten: A temporary memorial stands on the shore of Kampung Muara in Banawa, Donggala. The inscription is a list of the 41 people killed and 12 missing when most of the hamlet sank into the sea on Sept. 28. (JP/Ruslan Sangaji)

Not forgotten: A temporary memorial stands on the shore of Kampung Muara in Banawa, Donggala. The inscription is a list of the 41 people killed and 12 missing when most of the hamlet sank into the sea on Sept. 28. (JP/Ruslan Sangaji)

Mohammad Rafli, along with his fellow fishermen, was away at sea between Sulawesi and Kalimantan when a flurry of earthquakes shook the area at dusk on Sept. 28. They felt the jolt too but they thought their boat had hit coral and none had an inkling of what had hap-pened on land.

“I didn’t know there was a tsunami until we reached the land later that night,” the 40-year-old said during my visit to the fisherfolks’ new seafront home in Banawa district, Donggala regency, an hour’s drive north of Palu, last week.

Upon reaching the shore, they were shocked to find their village, Kampung Muara, was nowhere to be seen. The first thing that crossed their minds, Rafli said, was fear for the fates of their loved ones.

When eventually reunited with his surviving relatives, Rafli was told the quake — not the tsunami — sent the family’s house along with the 37 other houses in the village to the bottom of the sea. According to accounts, 41 people were found dead and 12 were still missing.

Others were lucky enough to escape. Others like Rafli were away at sea when the magnitude 7.4 quake struck. Now survivors stay at a shelter farther inland at Gunung Bale, still in Banawa district.

During low tide when the water is clear, the village ruins are visible from the surface. In remembrance of the victims, survivors erected a triplex “memorial” at the beach with a list of the dead and missing.

Kampung Muara was one of the best known fishing villages in Central Sulawesi. It began as a fish market and, as folk tales tell, it was officially named Kampung Muara, or estuary village, after its location.

Residents recall the village as a shopping center in Donggala. A resident, Lebba Mamobausat, says Kampung Muara boasted a movie theater when the provincial capital of Palu was without one.

They would proudly tell visitors that the kampung was the birthplace of Sigit Purnomo, aka Pasha Ungu, a pop singer-turned politician who is now Palu’s deputy mayor. His grandfather, Passamalangi, who lived in a two-story wooden house with his wives, narrowly escaped the disaster. The one house behind his was among those that sank into the sea.

Lebba says his father, Petta Mahmud, was the one who founded the village on the sandy beach in the 1960s. Petta’s success story drew more people from his kampung of origin in South Sulawesi. They are Bugenese, a Sulawesi ethnic group famous as seafarers. In the course of time, Kampung Muara attracted more people from other ethnic groups, who would regard Lebba as their revered leader and fishing guru.

The Donggala regency, which has a population of 302,000, suffered severe damage from the earthquake, with 171 deaths. Worst affected were residential areas along the coasts of the Donggala Peninsula.

Lende Ntovea village, some 100 kilometers north of Palu, was the closest to the epicenter. It was devastated. The whole village was leveled to the ground. No building was left standing. Land subsidence shrank hills, making them so small they appear as mounds, and main roads along the coast were destroyed.

Villagers say a dozen houses had crumbled when the first quake measuring 5.8 on the Richter scale shook the ground at about 3 p.m. When the bigger one followed, no building could withstand it.

“The first deaths had already been reported in the wake of the first quake,” says Ahyar Mahmud, a community leader.

Survivors left homeless have been accommodated on hilly ground away from the coastline and are awaiting substitute houses the government is building.

Devastated: Residents flock to what was the site of their homes destroyed or swallowed by the earth in the liquefaction

Devastated: Residents flock to what was the site of their homes destroyed or swallowed by the earth in the liquefaction

that followed the Sept. 28 quake in Petobo, Palu, Central Sulawesi.(JP/Ruslan Sangaji)

| Writer | : | Ruslan Sangaji |

| Photographer | : | Ruslan Sangaji |

| Managing Editor | : | Primastuti Handayani |

| Desk Editors | : | Pandaya, Imanuddin Razak |

| Art & Graphic Design Head | : | Budhi Button |

| Technology | : | Mustopa, Sandy Riady Hasan, Adri Putranto |

| Multimedia | : | Bayu Widhiatmoko |