Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsJakarta's 'sad clowns': Boon for costume businesses

The sudden increase in people hitting the streets in costumes has been a boon for the costume industry, but some point to the bigger issues of unskilled labor and an inadequate social safety net.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Part 2: Thriving costume business

It isn't all tragedy, however. On the supply side of the informal badut jalanan (street clown) sector, costume retail and rental businesses have actually been thriving during the health crisis.

Facebook Groups selling new and secondhand costumes see thousands of users looking to buy or sell costumes. One such group is Jual Beli Aksesoris Badut Se Indonesia (buy/sell clown accessories in Indonesia), which has at least 1,700 members.

Costume producers and suppliers are ready to ship their products across the archipelago, and the choices are endless. Looking for Marvel superhero costumes? Check. Want a bespoke costume? Check.

Prices range from Rp 500,000 to Rp 3 million, depending on the complexity and quality of the costume. Secondhand costumes come for much cheaper, so are a more affordable option for people turning to performing as badut jalanan to make ends meet.

For example, one Facebook user posted on a discussion board that they had a budget of Rp 400,000 for a badut jalanan costume, which prompted comments from about two dozen vendors.

For others, the strong demand has meant an opportunity to start a costume rental business.

One such entrepreneur is Paiman, who has declined to provide his full name. The 45-year-old Yogyakarta resident lost his job as a tourist bus driver after the COVID-19 outbreak hit the transportation sector. One day, a neighbor, an unemployed widow in her 50s, approached him to ask if he could help her find a rental costume.

“I asked her why she wanted to become a [street] clown,” he said. “She said it paid quite well. So I bought a costume for her to rent.”

That first costume cost Rp 2 million, which Paiman bought in May 2020 from a costume maker in Bandung, West Java, and rents it out for Rp 50,000 a day. He now has two costumes: one is the iconic Japanese cartoon character Doraemon, and the other is a cat costume.

Nine months later, and he says he has broken even.

Paiman usually offers his costume rentals on Facebook Groups, and he says he’s often flooded by inquiries from potential customers.

“I get so many texts and calls from people who want to rent my costumes. Most are people who lost their main income [source],” Paiman told me by phone. He added that he had to turn down the majority, since he had only two costumes to rent out.

“It’s not a good, sustainable business yet, but still enough to [get by],” he said. “If I had more money, I would buy more costumes. There is a demand for this.”

For Beth Febriansyah, a 24-year-old costume maker in Bandung, the badut jalanan phenomenon has been a boon for his business.

Beth (pronounced “bet” in Indonesian), established his costume-making workshop five years ago after apprenticing at a relative’s workshop. His workshop soon became the go-to place for companies looking to bring their branding to life in custom-designed costumes. But as the coronavirus continued to ravage the country, he found himself busy making costumes for a different type of clientele.

“We have fewer orders from companies due to the pandemic, but we have seen an increase in orders from people who just lost their jobs and want to make some extra cash to survive,” Beth told me by phone.

Before the pandemic, Beth produced around 50 costumes per month, mainly to fill orders from companies. He says he currently receives around 30 orders each month, still enough to retain his six employees.

His costumes range between Rp 1.2 million and Rp 3.5 million, and are shipped to Sumatra and Kalimantan in addition to his primary market of Java.

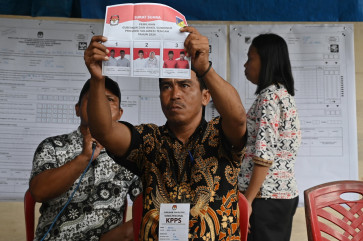

Prayitno, who heads the social rehabilitation division at the Jakarta Social Affairs Agency, said it had noticed an increase in costumed street performers in recent months, although he did not elaborate on the actual figure.

As for legal enforcement, Prayitno said the agency did not have the authority: “That’s the task of Satpol PP, to enforce the law if [street performers] are caught disturbing the peace.”

Read also: Jakarta’s ‘sad clowns’: Resilience and fortitude during COVID-19

He said the agency only provided social rehabilitation services for gepeng.

The term is the shortened form of “gelandangan dan pengemis” (vagrants and beggars), an official category that includes unskilled or jobless people asking for handouts.

“Once they have been rounded up, they are sent to our shelter for evaluation before [they are] sent to our rehabilitation center for skills training, such as in screen printing or as auto mechanics,” said Prayitno. He declined to comment when asked how many badut jalanan had received rehabilitation services.

Separately, the South Jakarta Satpol PP did not immediately respond to an interview request.

Anthropologist Yopie Septiadi at the University of Indonesia said the increase in badut jalanan laid bare the high number of unskilled workers and that the government had failed to provide essential training and jobs. The health emergency had only exacerbated the situation.

“Those costumes are just camouflage to cover up that they are actually unskilled labor,” Yopie told the Post. “It is no different than begging, because some of them do not even perform. In costume, most people look as if they are performing, which I doubt [they are actually doing].”

Badut sedih (sad clown), the vernacular for street clowns, does have some negative associations. This is particularly so because of the visible proliferation of street performers with their costume head removed, their sweaty heads hanging down and their furry-booted feet trudging down the street. Considering how heavy and hot the costumes are, this drudging appearance and movement makes sense, but some find it unnerving as a deliberate behavior intended to elicit pity and compassion.

Daffa Andika, a 26-year-old who runs the independent Kolibri Records in Jakarta, feels this way about street clowns.

“I was heading somewhere when I saw three to four clowns in just one trip,” Daffa told the Post, and that seeing them generated questions “instead of sympathy”.

“Are they really professional clowns, or people who are just trying to exploit the clown profession?” he said.

He also questioned how the “badut sedih” appeared to be organized, as if they had some form of leadership. But the Post did not find any evidence of organized coordination.

Daffa said he wished the street clowns demonstrated actual skills in performing or entertaining, such as magic tricks or acrobatics, instead of simply donning a costume and holding out a bag or basket to collect money.

“They all look very similar. Alone on the street, eyes gazing down, a sad expression and looking tired. I've never seen them do anything entertaining,” he added.

Taking an anthropological perspective on the socioeconomic phenomenon, Yopie said that as long as becoming a badut jalanan required little capital, the practice would inevitably attract more unemployed people if the government failed to provide a social safety net.

“Let’s look at it this way. Costumed [street performing] was once sacred and required skills, but the pandemic has made it profane,” he said.

Still, it must be said that some are genuinely trying to offer levity to others, no matter how kitsch the form, during this unprecedented, prolonged and multifaceted crisis that is the coronavirus pandemic.

And just perhaps, they are also applying a comedic approach to try and overcome their personal tragedies.