Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsWhat we know and don’t know about interconnection

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

For almost a month we have witnessed a neverending debate on issues related to mobile interconnection.

To cut a long story short, based on Communications and Information Ministry Regulation No. 8/2006 on interconnection, a circular was released on Aug. 2 mandating operators to reduce interconnection costs by an average 26 percent starting Sept. 1 (today).

The new regulation foresees the decline of interconnection from Rp 250 (1.88 US cents) to Rp 204.

Stakeholders are commonly divided into two opposing parties. Apparently, the largest operator and incumbent, Telkomsel, is reluctant regarding the plan while smaller operators (Indosat, XL and Smartfren) have welcomed the new regulation.

Meanwhile, the House of Representatives Commission I has warned the ministry to thoroughly evaluate the decision by taking into account information from all operators.

What do we know about interconnection?

First, as with any ICT product, telecommunications provides services to two distinct sets of users and thus is categorized as a two-sided market.

In the telecommunications industry, one side links an operator with end users and on the other side with other operator(s). The end users (retail price) and the wholesale price (also called interconnection or termination rate) are instruments in the supply and demand in each market.

Interconnection rates are the fees a telecommunications operator charges to another operator for terminating calls on its network in an off-net/between operators call. This charge should reflect the cost borne by operators.

If an interconnection rate is set above the cost, it will be in favor of the dominant operator to avoid competition pressure. In this case, smaller operators find it more difficult to compete as their off-net prices (when terminating with the incumbent’s subscribers) are higher than their own on-net price.

The phenomenon of “the club effects” can occur, denoted by high on-net/off-net price differentials, again giving the greater advantage to the incumbent as it owns a bigger network.

Second, interconnection should be regulated because of its natural characteristics as a monopoly: an operator has complete control on its own network (Economides, 2009; Banerjee, 2009; ITU, 2010).

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU) has set out principles for national regulatory authorities when calculating fixed or mobile interconnection rates. For example, the long-run incremental cost (LRIC) model is recommended as the methodology guaranteeing interconnection rates to be set based on the costs incurred by the most efficient operator.

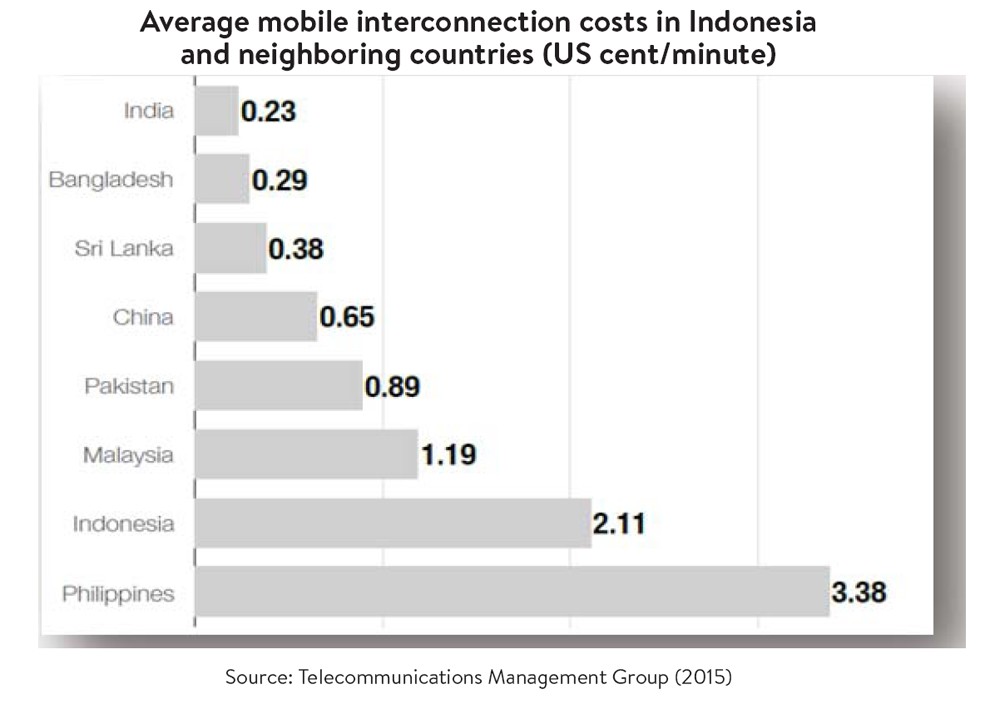

The figure shows (below) that Indonesian interconnection rates are still higher than those of neighboring countries. However, taking into account the country’s geographical characteristics, Indonesian operators might have heftier costs for the same type of investment.

What we do not know about interconnection?

First, what would be the impact on end users? Theoretical and empirical literature suggests interconnection might or might not be channelled to the retail price/end users (Banerjee, 2009).

The operator might use interconnection revenues as a subsidy. Therefore, if interconnection is somewhat high, they might save money and spend it on being able to offer lower access prices (subscription costs) and usage (call or SMS costs).

Therefore, if interconnection declines, they might neutralize this by increasing the retail price. This phenomenon is called the waterbed effect. Consequently, there will be fewer additional subscribers, preventing operators from investing more.

However, the opposite scenario also holds: lower interconnection rates followed by increased competition leads to lower retail prices, attracting more usage and subscribers. From this point, operators are motivated to invest more to stay competitive.

One of the key points here is the ability to foresee the response of end users to changes in the retail price, or price elasticity of demand. If the demand is quite elastic it means a 1 percent decrease in the retail price is responded to by a greater volume of demand.

In other words, reducing the retail price is a better policy for operators to maximize their total revenue.

Based on the Bank of America Merrill-Lynch Global Wireless Matrix, users in Indonesia are still very sensitive to prices compared with those in other countries. For instance, until 2013 the percentage of users changing operators over total subscribers (churn rate) stood at 11 percent, among the highest compared to neighboring countries’ ratios and more than double that in Thailand and the Philippines.

Using the same database it was also found that the price elasticity of demand (minutes of use) was about 40 percent, which means that a 1 percent reduction in retail price would increase minutes of use by about 40 percent. This aspect rationalizes why operators should pass on the reduction in interconnection to the retail price.

Research ICT Africa (RIA) conducted studies on the impacts of reducing interconnection in South Africa and Namibia. Their results show that despite very strong rejection from operators of the policy initially, they eventually reaped profits two years after the policy was implemented in 2010.

Vodacom and MTN recorded additional net profits of 1.14 billion rand and 741 million rand, respectively.

In Namibia, the reduction yielded an increase in the earnings before interest, tax, depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) margin by 50+ percent and more importantly transformed the incumbent operator (MTC) into the third-cheapest dominant operator in Africa.

In a more established market like Europe, the impact of reducing costs is even more apparent. ITU (2010) reported that eliminating price distortions across the EU was predicted to lower prices for voice calls, saving customers at least €2 billion in the 2009 to 2012 period, and stimulating investment in the telecommunications sector as a whole.

Second, how to define the most efficient operator? There is no crystal clear answer. There are operators with less capital expenditure that might have much lower unit costs. On the contrary, there are also operators that spend a lot of capital expenditure on endeavours to widen their market beyond what is currently established by reaching out to rural areas and customers outside of Java. This policy might increase the cost of interconnection especially in the shorter term when investment has not yet reached a level of efficiency.

To sum up, no operator builds a network solely to make money from interconnection but from selling services to their subscribers. Interconnection should be seen as an intermediate policy in which the impact on spurring investment and allowing users to access better quality services are the more important goal for regulatory measures.

____________________________

The writer, who obtained a PhD in technology management and economics at Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg, Sweden, is an ICT industry analyst who lives in Seville, Spain.