Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsWhen death becomes political: Return of the Greek tragedy

Today death, once more, has become political; indeed increasing political polarization has returned.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

n 1957, the anthropologist Clifford Geertz published one of his first articles titled “Ritual and Social Change: A Javanese Example” in the American Anthropologist journal, where Geertz cites the death of a boy, on July 17, 1954 in Mojokuto, East Java, and the tension that arose when religious officials refused or delayed the burial prayers due to the political affiliations of the child’s extended family. A village elder had told Geertz that “dying was nowadays a political problem.”

Today death, once more, has become political; indeed increasing political polarization has returned.

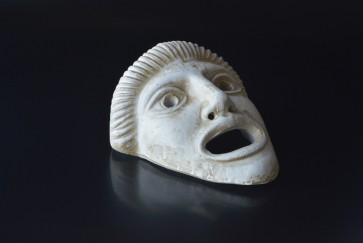

The refusal of burial prayers has a long history stretching to antiquity. The classical Greek tragedy Antigone and the Greek myth of the Trojan War are examples of stories that involve refusal of burial prayers for political or war-related issues. In Sophocles’ drama of Antigone, the King of Thebes Creon, refuses burial prayers for Polynice, a citizen who had rebelled against the kingdom. In the story of the Trojan War, from Homer’s Iliad, the Greek hero Achilles slays the Trojan prince Hector in battle and then refuses burial prayers, instead dishonoring the body in revenge for the Trojan killing of his compatriot, Patroclus.

The two stories were set in periods of violent conflict. In contrast, Geertz’s story occurs as a result of increasing political polarization in the run up to Indonesia’s first elections in 1955 since proclaiming independence. Geertz writes of increasing tension at the national level between the puritan religious political parties and the religiously syncretic nationalist parties.

At the time, the village religious official, allied to the puritan parties, refused burial prayers due to the deceased family’s affiliation to a religiously syncretic nationalist party. This refusal reflected the local effects of political polarization in daily kampong life.

Social scientists can interpret the refusal to perform burial prayers due to petty political reasons as an act of exerting power against the deceased’s family and community. Burial prayers and rituals help to restore social and emotional stability for the concerned community and family, due to its disruption by death, particularly sudden ones.

Refusal to perform burial prayers effectively co-opts and monopolizes control of religious symbols and rituals in the locality. It impedes the grieving family and community from gaining closure and forces them, amid emotional distress, to submit to the political will of those who control the rituals.