Pancasila, pluralism and election: Lessons from Istiqlal

The mosque was named “Istiqlal,” an Arabic word meaning “independence,” not only as a place of worship but more importantly to commemorate the nation’s freedom.

Change Size

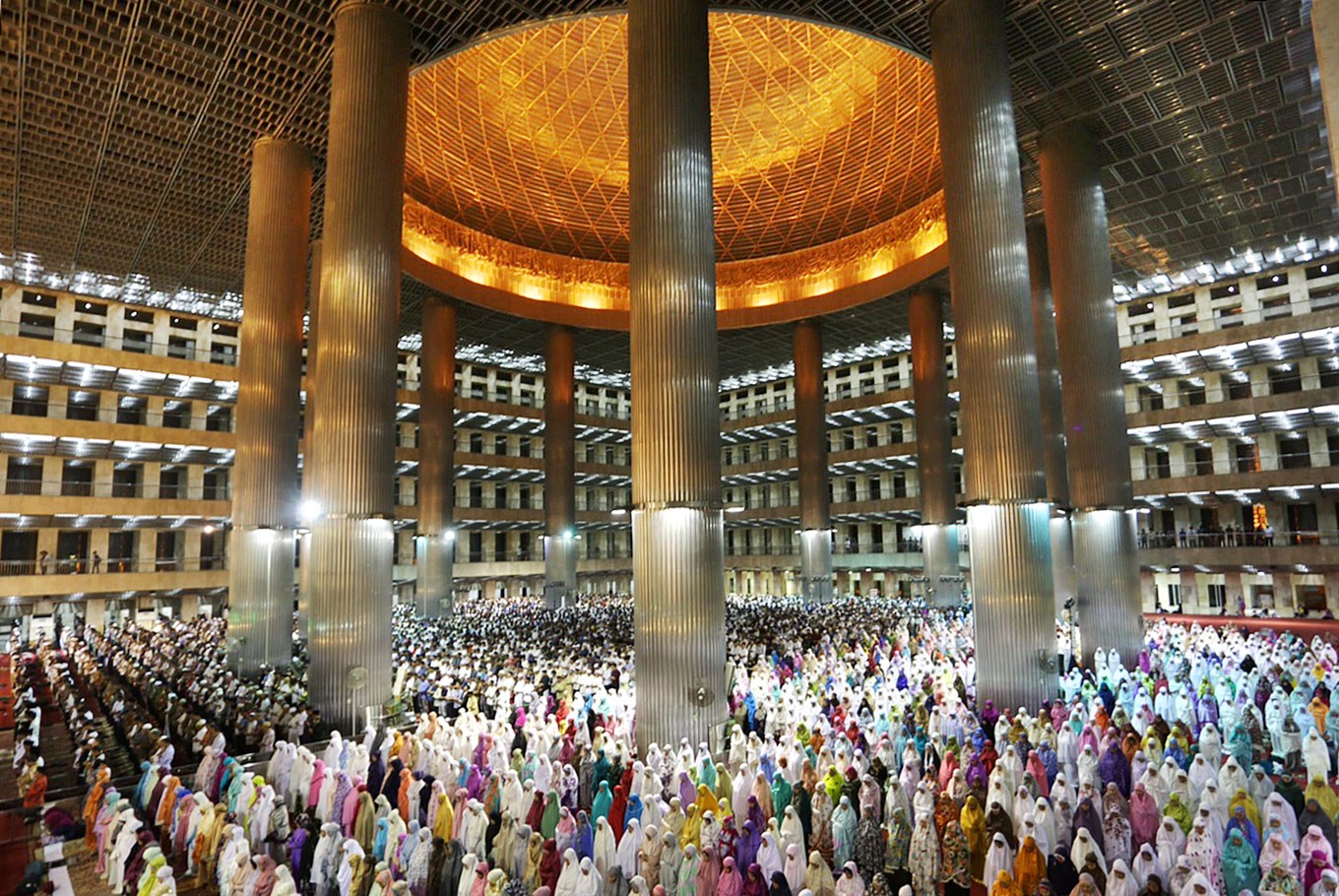

First prayer: Muslims perform tarawih (evening Ramadhan prayers) at Istiqlal Mosque in Jakarta on May 16, 2018, marking the beginning of the fasting month. (JP/Wendra Ajistyatama)

First prayer: Muslims perform tarawih (evening Ramadhan prayers) at Istiqlal Mosque in Jakarta on May 16, 2018, marking the beginning of the fasting month. (JP/Wendra Ajistyatama)

G

rowing up in Indonesia, I attended one of the most prestigious Islamic schools in Greater Jakarta. In kindergarten, I won a contest in reciting a verse from the Quran. I was also the student who got into trouble for having parents who brought doughnuts decorated with candles for her birthday celebration at school.

Candles, my teacher said, were “a Christian custom.”

It was the early 2000s. Despite my Islam-leaning education, I grew up in a multi-faith community. My closest friends in the neighborhood were of diverse Christian faiths and my American uncle is an Irish Catholic. I did not know what all the fuss was about. I simply wanted to celebrate my birthday with friends. As far as I was concerned, candles were a universally-accepted way of celebrating another year of life.

Later I realized that what I had experienced while I was only five years old was among the early signs of the decline in our state ideology Pancasila, from which we have learnt respect for diversity. Such signs peaked into events leading to the imprisonment of former Jakarta governor Basuki "Ahok" Tjahaja Purnama for blasphemy following his loss in last year’s Jakarta’s gubernatorial race, widely recognized by the international community as a major setback to Indonesia’s democracy.

As Indonesia prepares for the upcoming 2019 presidential and legislative elections, let’s all remember one of Indonesia’s most important monuments: the Istiqlal Mosque in the heart of the capital, a symbol of first president Sukarno’s wish for a burgeoning democracy back in the 1950s.

Despite Indonesia’s historical ties with Islam, it did not declare itself as an Islamic state upon independence from Dutch colonial rule in 1945 — Sukarno chose Pancasila as the new nation’s ideological and philosophical foundation. The mosque was named “Istiqlal,” an Arabic word meaning “independence,” not only as a place of worship but more importantly to commemorate the nation’s freedom.

To reflect his vision of a multi-faith nation based on the archipelago’s diversity, Sukarno deliberately chose to build the mosque near the Jakarta Cathedral to symbolize religious harmony. Both national houses of worship are located in the Merdeka Square area, which symbolizes freedom or independence. In addition, the mosque was designed by Frederich Silaban, a Christian architect of Batak ethnic group in North Sumatra.

To mainstream Muslims, the mosque stands as a symbol of their faith and of Pancasila. The mosque has seven entrances, seven being a divine number in the Abrahamic religions: Islam, Christianity, and Judaism. While it is first and foremost a house of worship for Muslims, its location across the Cathedral symbolizes religious harmony. During Christmas mass, the mosque’s parking lot is used by the Cathedral’s congregation, and vice-versa during Idul Fitri prayers.

In Pancasila, all five pillars conform to the fundamental teachings of Islam: faith in God, humanity, unity, democracy and social justice. Further, Pancasila embraces diversity and plurality of ethnicity, culture, and faith. Evidently the mosque was built not just for Muslims, but for all Indonesians. That the mosque was commissioned by a president who desired to blend the faiths and philosophies of the nation as a new republic was a commitment worthy of note.

While the Istiqlal stands as a symbol of religious plurality and Pancasila, Indonesia still needs much practice as a nation to live up to the message behind the mosque.

Clearly candidates for the April elections have not ignored the events of 2017. President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo chose as his running mate Ma’ruf Amin, then leader of the largest Islamic organization Nahdlatul Ulama and leader of the Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) who signed the fatwa on Ahok’s blasphemy of a Quranic verse.

Despite NU’s generally moderate outlook, Ma’ruf was infamous for his relatively hardline and controversial views against religious and gender minorities including gays.

By picking Ma’ruf, Jokowi is setting the stage for potentially more inflammatory sentiments against minorities, weakening his commitment to religious plurality and thus Pancasila.

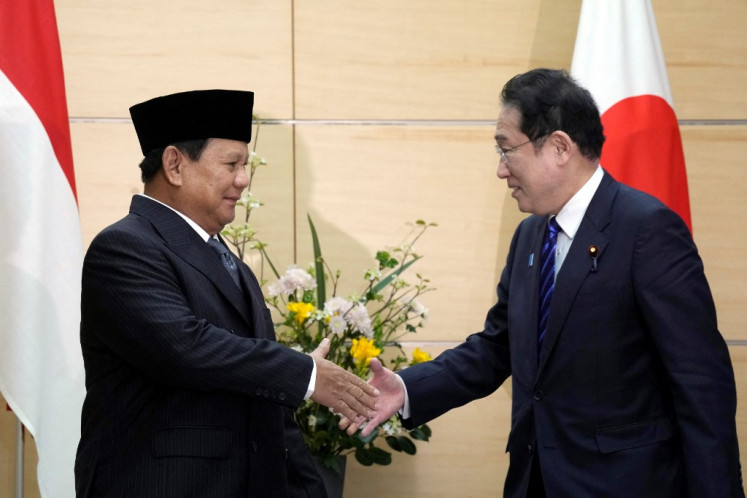

Meanwhile his rival Prabowo Subianto and his allies have reportedly linked up with Islamist groups who earlier mobilized against Ahok. His conservative Muslim base gets his message that he will protect their interests; his vice-presidential pick in Sandiaga Uno is also detrimental to Indonesia’s democratic development. Sandi, as he is called, is well known as one of Indonesia’s richest politicians with little political experience, despite being former Jakarta deputy governor. How would the duo protect the rights of religious minorities?

At its current state, Indonesia’s 2019 presidential race already shows a significant rollback of democratic values. However, there is still hope.

Two weeks before I flew to Jakarta from Washington for my first winter holiday in Indonesia, I saw a former classmate who now wears a hijab, singing in a Christmas concert as part of a multi-faith university choir. I saw multiple friends in Jakarta in ugly Christmas sweater parties. When I arrived in Jakarta, “It’s Beginning to Look a Lot Like Christmas” was playing on the radio, as we drove away from Soekarno-Hatta International Airport to streets lined with Christmas lights and decorations.

This was not the Jakarta I knew in the early 2000s. This is the Jakarta that president Sukarno had envisioned through Pancasila. We ought to remember his wishes as symbolized in the Istiqlal Mosque built across the Cathedral — those of us who are part of the Muslim majority standing in front of and alongside our brothers and sisters in the margins who express their faiths differently. As the elections loom closer, as moderate Muslims in a secular nation it is our duty to protect the rights of the religious minorities and ensure a democratic Indonesia.

***

The writer is an Indonesian-American master’s in international affairs scholar at the George Washington University in Washington, DC. She studies United States’ foreign policy and international law, focusing on Southeast Asia. She works at the US House of Representatives and is a fellow at Mothership Strategies, a progressive digital agency in DC.