Telling stories of Indonesian fabrics for internet-savvy generation

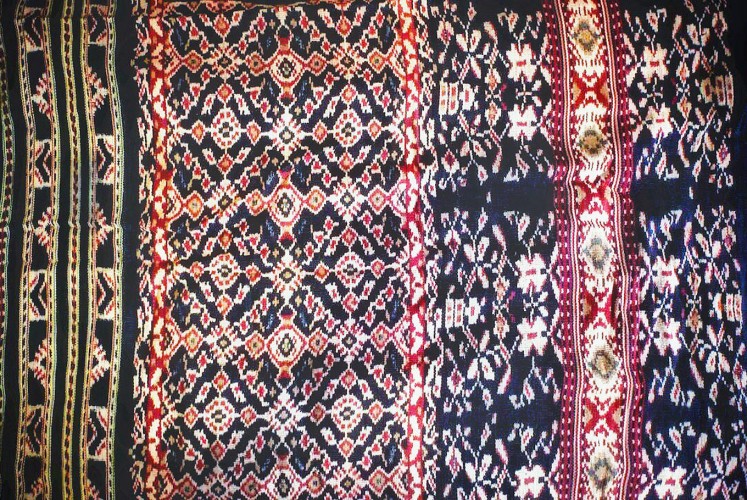

Fabrics, like most historical silent artifacts that Indonesian hands make, bear witness to stories told by their weavers — from grandmothers to their daughters.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Work in progress: A weaver from West Sumba, East Nusa Tenggara, weaves a piece of fabric. (Thomas Brown/File)

Work in progress: A weaver from West Sumba, East Nusa Tenggara, weaves a piece of fabric. (Thomas Brown/File)

F

reelance journalist and researcher Grace Tan-Johannes went back to East Nusa Tenggara with the entire history of her ancestry in the back of her mind. And she found some parts of it in an object her great-grandmother once made: a tenun ikat fabric with bunga perang motif.

“My ancestral knowledge does not lie in books or the internet, but in the minds of elders who are dying faster than I can catch them,” she wrote in a blog post titled “The Almost-Death of Bunga Perang”.

You can find “The Almost-Death of Bunga Perang”, along with other stories of fabrics spread across Indonesia on a non-profit blog called Kain Kita (Our Fabrics), hosted on the website Medium.

Fabrics, like most historical silent artifacts, bear witness to stories told by their weavers. Chief among them are the kain kapal of Lampung, South Sumatra, stagen of Central Java and the many ikat weavings of Toraja, South Sulawesi.

Relying on contributors and their own stories, Kain Kita is the brainchild of Indonesian researcher and writer Nurdiyansah Dalidjo and Cassandra Grant, an Australian writer and development worker.

They came up with the idea early this year and their primary motivation was to tell stories that the archipelago inherits for its younger, internet-savvy generation.

“The truth is, these fabrics tell many stories, not just from their aesthetics or their motifs, but also the techniques to make them — how to wrap, apply natural color and more,” Nurdiyansah told The Jakarta Post.

Though it may sound taxing, Kain Kita’s affinity for a wide-reach is right there in the languages chosen for the stories. Each story is written in Indonesian and English, as Grant or the authors themselves help with the translation.

“While there was a groundswell of interest in kain among Indonesians, the international perception of Indonesian fabrics has centered on Javanese batik and ikat weavings from eastern Indonesia. We knew there were other intriguing stories of kain that might also connect with a global audience,” Grant told the Post.

She cited as an example the ship motifs in kain kapal from Lampung in South Sumatra, which tell the story of their ancestors’ journey migrating from Vietnam.

“Other contributors have reflected on reconciling their heirloom tenun with their international identity. By providing translation support and sharing these stories in both [Indonesian] and English, our project provides a platform for international readers to encounter more Indonesian voices,” Grant said.

Weaving is just one of several labor-extensive ways to process a piece of fabric. To prepare cotton, for instance, you’ll have to extract colors from natural sources — this takes dying, re-dying, drying and more. It takes months or even years to complete.

According to Nurdiyansah, weaving is a domain for women — though not universally.

“In Palembang, the weaving of songket was done by women. But as the industry grew and created new jobs, men joined in as well,” he said. “Generally, women are the weavers and [they] make batik. My friends and I noticed that fabrics are a manifestation of traditional rights.”

Those rights, Nurdiyansyah said, include collective rights and women’s rights for wisdom.

“Women can reclaim a specific role in a given community.”

Fabrics stand at the intersection of sacred traditions and commerce. With regards to the latter, its laborious process results in expensive fabrics. Thankfully, innovation — including non-machine weaving tools like the one found in the manufacturing of kain tenun troso in Jepara, Central Java — helped spur more affordable fabrics.

Even so, problems still abound. For instance, the United States Department of Agriculture in its April 2017 report wrote: “Indonesian cotton production is very low, as farmers continue to face better incentives to grow alternates such as rice or corn.”

Dinny Jusuf, CEO of Toraja Melo, an organization that focuses on the fair distribution of fabrics and weavers’ empowerment, said Indonesia lacked agricultural strategy, noting that weavers in Toraja tended to buy the necessary threads in bulk from Makassar-based distributors.

“Because the threads are from Makassar, they cater to the taste of the Makassar market,” she said.

Dinny said that fabrics might be subject to price gaming, as stated in a story about stagen on Kain Kita.

Stagen literally means a woven cloth that Javanese women usually use to flatten their stomach while wearing a kebaya (traditional blouse) or after giving birth as a traditional wrap.

Having tirelessly worked to lobby the government for, say, silk worm or cotton farms, Dinny said determining factors necessary in the wide distribution of traditional fabrics are geographical indicators. “For instance, these are Toraja fabrics, not Troso’s,” she said.

These items may just be wearable to some, but sacrosanct to others.

“In Baduy or Kanekes Dalam, weaving is considered a mediation or a prayer. In the Batak tradition, ulos is also considered a prayer, woven when women marry off their children or when they [the children] are about to give birth. Ulos ragi tohang is also used to pray for a longer marriage. It’s not for sale,” Nurdiyansah said.

In its efforts, Kain Kita joins the ranks of designers like Biyan Wanaatmadja who paid homage to the Sumba motif with his collection.

Nurdiyansah said Kain Kita already has more stories to tell. Rest assured that respect will anchor these stories, which include the songket or Maluku’s weavings.

“Acknowledgment, whichever form it takes, is key,” he said