'The one-billion-rupiah painter' finds solace at Yogyakarta’s Kasihan

A former political prisoner, renowned artist Djoko Pekik outlived his persecutors, retaini

Change Size

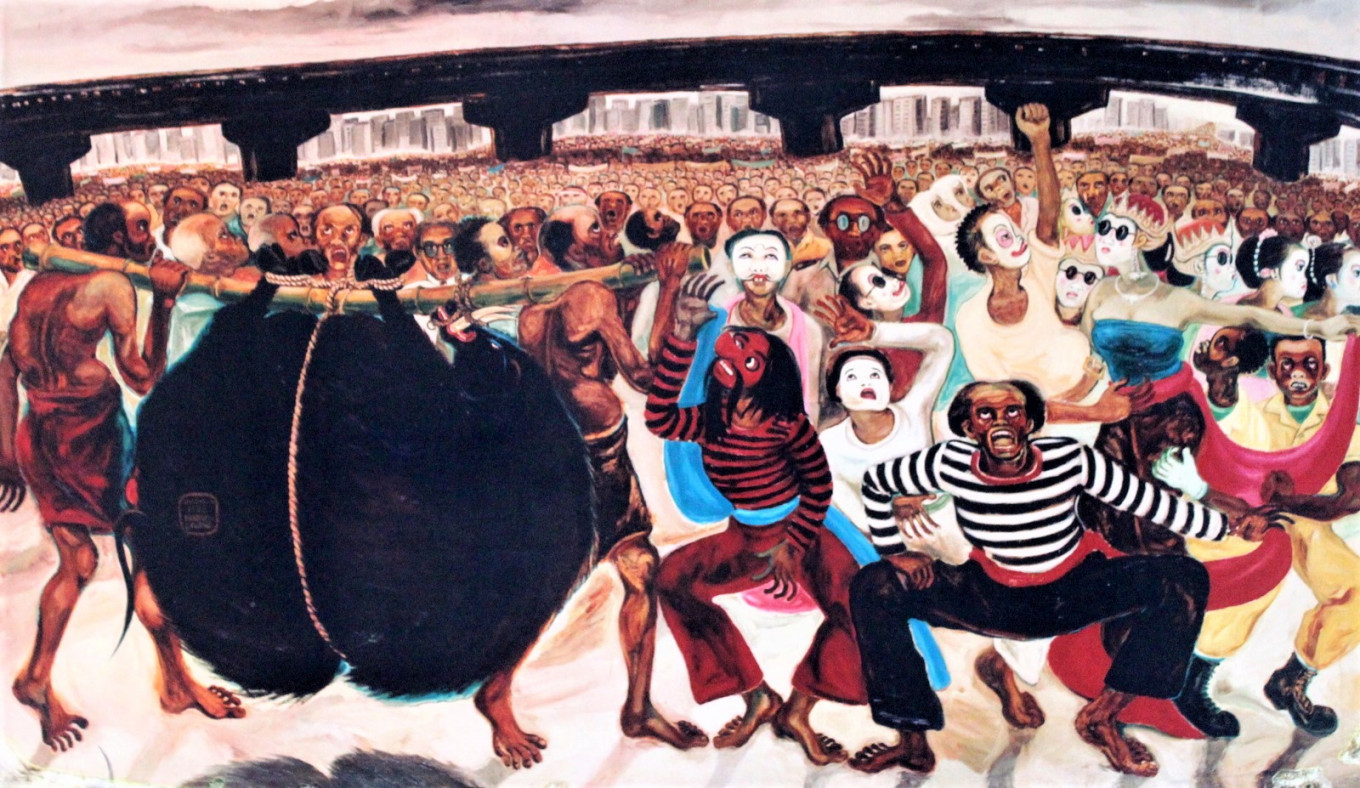

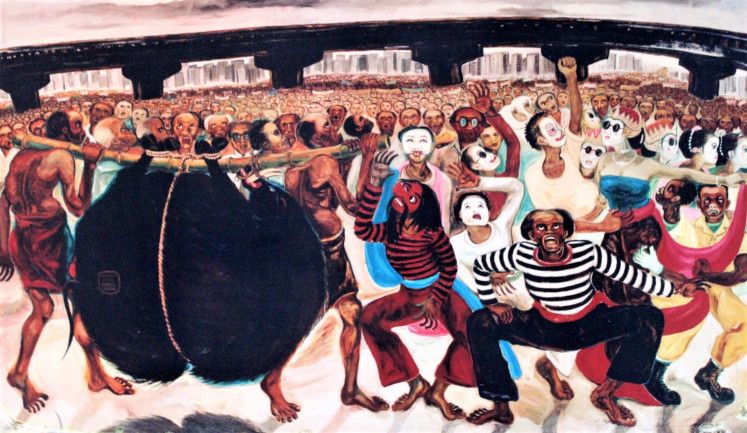

Iconic art: Berburu Celeng (Boar Hunting) is the painting that earned Djoko Pekik the moniker, “the one-billion-rupiah painter”. (Erlinawati Graham/-)

Iconic art: Berburu Celeng (Boar Hunting) is the painting that earned Djoko Pekik the moniker, “the one-billion-rupiah painter”. (Erlinawati Graham/-)

T

he Indonesian word “kasihan” is commonly used to express consolation for a hardship, a loss, an accident, a mishap. It is also the name of a hamlet in Bantul regency, just outside Yogyakarta.

Low lying, more forest than field and with an abundant supply of water, Kasihan hamlet is known as a lush den of imagination and inventiveness, with six of the 14 nationally renowned daughters and sons from the village involved in the arts.

This is no surprise because the nearby spring called Pengasihan – which literally means “be merciful” – is reputed to have curative and mystical powers and once drew the local royalty to meditate there. Now it seduces creatives.

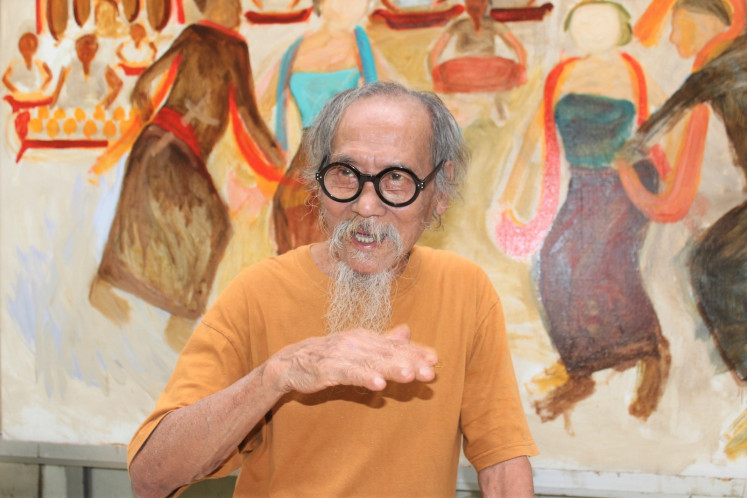

Most famous of the artists who live here is Djoko Pekik, who has transformed the bush into a striking studio and gallery to preserve his huge “crowdscape” paintings.

One of Pekik’s admirers is Giring Prihatyasono, a 39-year-old graduate of the prestigious Indonesian Arts Institute of Yogyakarta and a social commentator, although he possesses a formal, controlled style while his guru is free and forceful.

The younger artist explores different materials, particularly aluminum. It’s a costly metal though one that yields beguiling and ambiguous results when etched.

Giring’s work is subtle and pensive, often including a rent or scar as though it’s been accidentally snagged. This is deliberate, and part of his philosophy. “We strive for perfection, but it’s impossible to achieve. So after trying to make my work as good as it can be, I add a flaw,” he says.

In his early days, Giring tried producing paintings of the kind the shops liked to sell to tourists, like smiling girls in rice paddies, but that didn’t satisfy him. He was also fascinated by language and how various lettering systems had evolved around the world.

“Now I work to express myself. Artists should be honest and let their creations find the buyer,” he says.

His determination has found enough collectors to keep his family in better straits than if he’d followed his father to work at a sugar factory – a refusal that led to silent mealtimes for a year. They’re now back on speaking terms.

The winner of multiple awards conceals his messages. A large disc that at first looks to be a state emblem is circled with the faint words: “Sebagai Abdi Negara saya malu dan tidak akan melakukan korupsi (As a servant of the nation, I am ashamed and will not participate in corruption)”.

A 5-minute walk from his hideaway – through the tangled undergrowth across a narrow bridge above Khonteng stream and along damp tracks that wend past the houses of other painters – eventually leads to the studio of the artist emeritus.

Giring feels for his country but hasn’t suffered for his art like Pekik, who was once a member of Bumi Tarung (fight for the land), a gathering of creatives during the Sukarno era. It was savagely persecuted by his military successor Soeharto, because most artists leaned left.

They were treated like terrorists, but they were intellectuals, not bombers. The weapons they wielded were their ideas, pens and brushes.

After seven years of brutality and deprivation, Pekik was released from jail with “TP” for Tahanan Politik stamped on his identity card, identifying him as a former political prisoner. This label made him almost unemployable and unacceptable to society. For several years, Pekik cleaned sewers to support his eight children.

His revenge was splendid. In 1999, a year after his persecutor Soeharto was dethroned, Pekik gained fame as the first painter in the country to sell an artwork for Rp 1 billion (then about US$120,000). The painting in question was Berburu Celeng (Boar Hunting), now an icon of Indonesian contemporary art.

Most assumed that the fat wild pig, trussed upside-down on a pole carried between hunters was the republic’s second president. Soeharto also seems to be the ringmaster in Sirkus September (September circus), a reference to the 1965 coup that felled Sukarno. Two big black rhinos clash their horns in the foreground, urged on by clowns.

Pekik, like a novelist advised by a lawyer, has denied any resemblance to persons living or dead. As a social realist, he’s blunt on the canvas but equivocal in conversation.

“You see what you want to see,” the 83-year-old said, sitting before a motorized easel as he moved his work up and down. “You’re the viewer.”

His nationalism is stark and xenophobic: If he doesn’t like a foreigner, he orders them off his property even if they’ve come to buy. “The colonialists were bad, but not as bad as the Japanese,” Pekik says.

He relies on nicotine and paint to smother the memories, though not to forget the cruelty and horrors. He has outlived his persecutors, retaining his dignity and independence.

Pekik may now be rich, but he still rails against the oligarchy and big business, always siding with the wee folk. Sometimes he depicts them brandishing spears. The angry confronters are dramatic in their intensity, though they are often flanked by powerless onlookers.

He admits his 2014 canvas Go to hell, crocodile is a commentary on the Freeport mine in Papua: A crowd faces a giant, scaly reptile lapping blood from a swirling void. Some have linked the painting to Sukarno’s well-documented 1964 outburst against the US: “Go to hell with your aid!”

Pekik’s figures are seldom static: dancers swish, black smoke chokes the crowd. These are not images to soothe. The colors are usually subdued, though his clowns are gaudy. “That’s to show happiness,” he said, though unconvincingly.

“Who cares how it all ends? As long as I can keep painting my thoughts and visions, then everything’s fine.” Kasihan? “No,” he responds.(ste)