Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search results‘NKRI harga mati’, or peace for Papua?

Papua is the big half of Indonesia’s largest island that most Indonesians have never been to

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

P

apua is the big half of Indonesia’s largest island that most Indonesians have never been to. But cut it out of the map of our tanah air (archipelago, land and water) and we are left with a big gap: It just doesn’t look right and is totally unacceptable to what all Indonesians grew up with, beautifully starting with the island of Sumatra, sloping down to Java with the large islands in the middle, tiny gems on the top and others trailing off Java and ending with that big mass of Papua with a bird-like head.

But is this map and Papua’s bountiful resources all we care about?

With all the reports of violence stemming from the easternmost provinces, the latest following the declaration of independence at the Third Papua People’s Congress in Abepura last month, questions have again emerged over Papua’s prospects for peace.

There is no war going on there, but frequent deployment of security forces suggests there is. Or maybe there isn’t. Part of the problem is that not much information is made available — not that many Indonesians really care, except when it comes to that map.

In reaction to aspirations of independence, one might hear the phrase “NKRI harga mati!” A rough translation: The Unitary State of the Indonesian Republic (NKRI) or death! Indonesians love catchy phrases — this one picked up from military jargon.

It means we must defend the Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia by force if necessary. However, reacting to signs of subversion by separatists, violence is the rule, not the exception, even if for years

Papuans have asked for “dialogue” with Jakarta.

The sense of nationalism, molded under the authoritarian New Order where the military played a central role, has come to mean that no one would raise an eyebrow if force was used, as was the case at the bloody end to the Abepura congress.

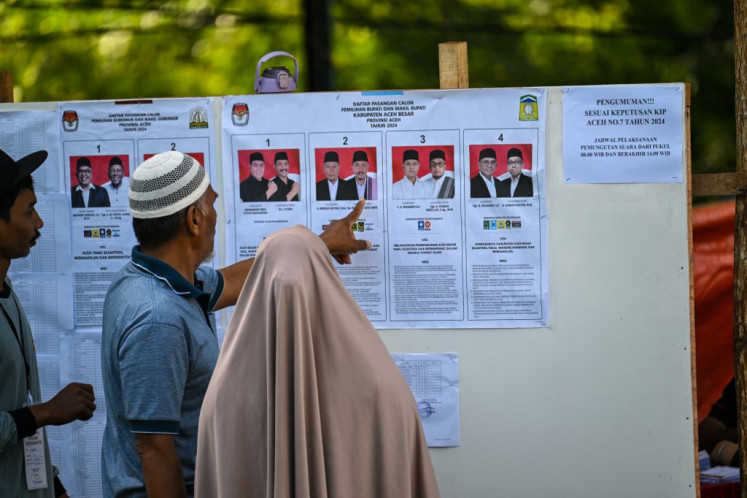

In Indonesia’s post-Soeharto democracy, which has seen a historic peaceful settlement for Aceh, it is this militarized nationalism that remains predominant.

A similar reaction was initially made to the government’s negotiations with the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) – but the Ground Zero created by the 2004 tsunami and earthquake forced the rebels and government to finally concede what each side never conceived possible: GAM dropped its independence demands and the government agreed to give Aceh the sole privilege of having its own local political parties.

Indonesia also finally had to let East Timor go, as this was what most Timorese voted for in an internationally monitored referendum.

But no comparable international spotlight exists for Papua. We will have to wait and see whether the meetings of Farid Husain, the go-between for Jakarta and GAM, and a number of pro-independence Papuan leaders, are a sign that the government is moving toward serious efforts for peace. Other signs are not so encouraging.

Last year President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono announced that the government would not engage in a “dialogue” that Papuans have long requested; in typical Yudhoyono form, the term he used was “constructive communication”, which left many people confused.

The 2001 special autonomy law was already quite progressive, with special recognition of Papuans’ representation in the Papuan People’s Council (MRP). But then this MRP’s authority in making laws was diluted, and new provinces were created, with the MRP confusingly representing “Papua” only.

Furthermore, Papuans cite how they are increasingly disappearing from the urban landscape and are being replaced by migrants while the central government’s heavy-handed “security” tactics remain in place.

Legislators have even questioned plans to set up new territorial command structures (Kodam) in light of military force being used to settle problems beyond battling the OPM, such as land conflicts, strikes and protests. Before the Abepura congress, a Freeport employee was shot dead when security forces attempted to break up a strike near its Grasberg mine.

In the case of Aceh, SBY and Jusuf Kalla were finally able to contain the military and politicians — who were vehemently against negotiations with GAM and the concessions given to them — mainly with the local political parties and the withdrawal of the TNI (with compensation amounting to US$50 million, according to reports). Like Timor Leste, Aceh was under the international spotlight.

Papua has recently attracted considerable attention for the wrong reasons, as usual. But does SBY have the upper hand over the TNI, as he did in the case of Aceh? The frequent violence this year involving security forces in Papua suggests Jakarta is closing its eyes or is unable to discipline its soldiers, or it is deliberately warning residents against showing any sign of support for the insurgency (regardless of its real strength).

A lack of access to information contributes to uncritical support for the “NKRI or death!” approach, regardless of the Papuan peoples’ grievances and aspirations.

The author is a staff writer of The Jakarta Post.