Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsA town of sleaze with no calendar

You wouldnât want to stay in Paruk, even if it was the only sanctuary available during a tsunami

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

You wouldn't want to stay in Paruk, even if it was the only sanctuary available during a tsunami. If the fare didn't finish you off, the supernatural would ' be extra wary for comets portending tragedy.

This fictional Javanese village is not the quaint abode of gentle rustics who maintain benign traditions while nurturing their fertile slopes.

In the words of Ahmad Tohari, the author of the trilogy The Dancer, the people of Paruk are 'impoverished and backward ['¦] thin, sickly [and] foulmouthed'. Among this crew of dirty old men and their conniving wives there's just one attractive inhabitant, a talented artist called Srintil. She's inherited the spirit of a long dead ronggeng dancer to become a seductive performer who 'wooed without words, enticed with the power of magic.'

Srintil was one of the few survivors of a mass poisoning that overtook Paruk in the midst of a drought when many townsfolk died after eating contaminated food. Raised by a couple of relatives, she exhibits her talents at an early age and is soon returning fame and fortune to her otherwise blighted birthplace.

She becomes a prostitute, which is her destiny, but falls in love with her childhood sweetheart Rasus, who at times takes the role of narrator. He gets into the army by accident and finds religion, although he remains consumed by desire.

Although we're told the people of Paruk don't keep calendars, readers who know the recent history of Indonesia will sense calamity coming. For this is 1964 and a communist agitator called Bakar (meaning 'burn') is stirring up the folk, even though they have little interest in abandoning their apathy and don't even understand the meaning of 'proletariat'.

Doom approaches and although Srintil wants to stop being the party's propaganda dancer, it's too late. Dreadful things are happening in distant Jakarta's crocodile hole and Paruk is about to be dragged into the pit.

This is a difficult book to grasp emotionally. Some of it is porn, with which the author gratuitously embellishes the story, but there's always been a level of obscenity lurking beneath the politeness and respectability of Javanese culture.

The Serat Centhini (The Javanese Story of Life) commissioned by Surakarta Sultan Pakubuwono V early in the 19th century is so full of sex that translations into modern Indonesian are reportedly still unavailable.

So it is surprising that this book was ever published back in the more uptight early 1980s when the censor was king. It was first serialized as Ronggeng Dukuh Paruk (The dancer of Paruk Village) in Kompas, a high-standard broadsheet keen on promoting literature that had a reputation for being serious, not salacious.

American ethnomusicologist Rene Lysloff, who translated the text, came across a bound copy of the book by chance when undertaking research in Banyumas (Central Java) and found it fitted his fieldwork.

'I pondered the ethnographic truth of the novel, wondering whether fiction could be separated from fact in its depiction of an isolated Javanese village and the people who lived there,' he wrote. 'I felt certain that he [Tohari] had described a real world within the fiction of his novel.'

A ghastly conclusion, for if Paruk and its vile residents represent reality, the police and child protection authorities should be heading into the hinterland right now armed with warrants.

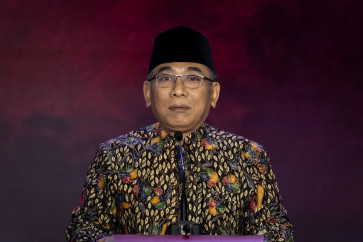

Yet the author is renowned, not as a smut merchant but as a scholar and prolific writer, a Muslim intellectual who advocates a holistic understanding of Islam, 'one that embraces existing forms of culture'.

At the end of the second book in the trilogy, A Shooting Star at Dawn, the communists break with the culture that nurtured them by vandalizing the graves of the village ancestors. Then arsonists attack. After the coup of Sept. 30, 1965 the slaughter starts.

In the final book, The Rainbow's Arc, Srintil is imprisoned and raped, although not before Tohari has laid some ground rules for the reader, including 'the courage to acknowledge historical truth.'

This is an astonishing statement when set against the current blindness towards the massacres, despite some debate flowing from American filmmaker Joshua Oppenheimer's The Act of Killing.

How did this taboo topic even get into print 30 years ago? Apparently the version in the book is not the one that appeared in Kompas, which was written to fit the government's view of events.

The horrors, the killings, the moral questions raised and the whole sickening purge of communists, sympathizers and even those like Srintil and her neighbors who had no interest in politics, is confronted.

Here The Dancer finds its worth, although the dilemma remains: In the earlier chapters, Paruk and its people are painted in such lewd hues that it's difficult to feel great sympathy when they are treated brutally.

They didn't deserve such a fate ' no-one did. They were victims because they were ignorant, ordinary people with simple beliefs who became useful scapegoats in Soeharto's time of terror.

Does this mean they are at fault? In this context the story seems to bypass the author's aim to honor the nation's culture and traditions.

Tragedy befalls Paruk 'because it never tried to find harmony with God', whatever that means. Lysloff helpfully adds an endnote explaining that the author wanted to describe a community 'entirely without contemporary notions of sin and virtue', and in this he has succeeded.

He has also mastered the tricky art of keeping the reader on track, even when we have little empathy with the characters. This is stirring drama covering the most significant years since the birth of the nation.

Some claim it's been written with raw honesty to make Indonesians see themselves without the benefit of a government lens. Others dismiss Tohari's work as so much indulgent fantasy that shames a modern nation with strong religious values. For this reviewer the former explanation carries most weight.

The Dancer

by Ahmad Tohari

Translated by Rene TA Lysloff

Lontar, Jakarta, Modern

Library of Indonesia, 2012

462 pages