It’s all over now for Rolling Stone Indonesia

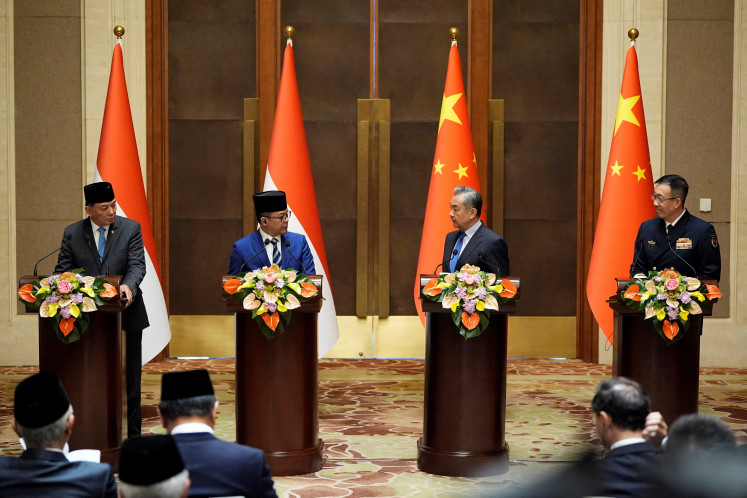

Rolling no more: The office of Rolling Stone Indonesia magazine is seen at Jl

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

R

span class="caption">Rolling no more: The office of Rolling Stone Indonesia magazine is seen at Jl. Ampera Raya No. 16 in Cilandak, South Jakarta. The magazine announced on Jan. 1 it had ceased publication.(JP/Ben Latuihamallo)

Late in December 2017, employees at the Indonesian music magazine Rolling Stone Indonesia announced almost in succession their exits from the magazine on their social media accounts. From its editor-in-chief Adib Hidayat, to editor Wendi Putranto, to staff writer Ivan Makhsara, their announcements, along with the timing — ignited speculation over the fate of the magazine. At best, what was going on? At worst, was it closing?

It did close. On Jan. 1, Rolling Stone Indonesia’s publisher PT a&e Media announced that as of that day, they no longer held the license for the magazine or the website to operate in Indonesia, according to the magazine’s website. Now any links to articles at its property return a harrowing “file not found” notice.

The closing of one of Indonesia’s biggest online and print music publications landed a fresh blow to the state of print media in the country. Last June, Indonesia lost the magazine Hai, which pivoted to online publishing, while in December, magazines FHM Indonesia and Esquire Indonesia closed up shop, following the fate of music magazines Trax, Aktuil and Ripple.

Aside from publishing articles on music-related news, profiles and reviews of music and films, Rolling Stone Indonesia also pushed beyond the boundaries of geography through its running feature Scene N’ Heard. Cover stories were also part and parcel; from pop singer Agnez Mo to indie pop band SORE, numerous faces graced the front cover.

The magazine began in May 2005, when household reggae household act Bob Marley appeared on the cover of its first edition. Legendary Indonesian rock band Slank was also featured at that time.

Indonesia was the first Asian country to welcome the outreach from its parent company and namesake Rolling Stone, a magazine started in 1967 by Jann Wenner and Ralph J. Gleason. In September 2017, Wenner put the company’s controlling stake up for sale, and Penske Media bought it three months later.

Since its inception, Rolling Stone Indonesia has left an impermeable mark on the Indonesian music scene. It also serves as a directory of the country’s past releases, as proven by the list of the 150 best Indonesian albums and songs of all time, released in 2007 and 2009, respectively. The magazine also steadily put out a list of the best Indonesian albums of each year, with 2017 being the last (pop singer Danilla’s second album Lintasan Waktu [Time’s Passage] earned the top spot).

But for aspiring music journalists, its legacy remains seared in their careers.

Raka Ibrahim, who now writes for the website Jurnal Ruang, said Rolling Stone Indonesia was the reference point for people who write about or are simply fans of music.

“It became canonical to determine which releases were important and which ones weren’t,” he said.

Raka, who has an alternative music website called Disorder Zine, believes it is important that local zines and magazines expand their reach so music can be more egalitarian and varied. Thus, “music journalism is no longer Jakarta-centric, no longer predicated on a singular taste.”

Farewells were posted on social media platforms like Instagram, including from indie rock bands Scaller and Efek Rumah Kaca. For musicians, Rolling Stone Indonesia was instrumental in their rise.

“Their coverage motivated us to continue to make music,” said Giovanni Rahmadeva, drummer of indie rock band Polka Wars, who was designated as one of the up-and-coming “young guns.”

Giovanni said Rolling Stone Indonesia disregarded any lines keeping musicians within the confines of the industry. “From the upper echelons to the lower, [the musicians] meet at the center,” he said, adding that Rolling Stone Indonesia prized quality of films and music above the established renown.

Ade Paloh, a member of SORE, also echoed the crucial presence of the music magazine.

“It was an impartial platform that lent the spotlight to anything that made sounds, without hierarchy, and did it through writings and reviews that would always have a message,” he said.

Losing a home and a source of income, predictably, was not easy for its former employees. Ivan Makhsara said to date, he still felt a grave sense of loss.

“In 11th grade, when I originally wanted to be a film director, I decided that I wanted to be a music journalist instead,” he told me. “Suddenly I no longer lost only a job, but also a home.”

Editor Reno Nismara said there were big chapters ahead.

“Now’s not the time to stay put, and that goes for the others, too,” he said. Many of his fellow workmates have started blogging again, and he said he could devote his time to the collective he is a part of, called Studiorama.

It is safe to say Rolling Stone Indonesia had a good run after 12 years. Or as Ivan put it “To this day, it’s safe to say that everyone there worked according only to their passion.”