Palm oil diplomacy for Indonesia’s most valuable commodity

The palm oil sector plays an important role in the Indonesian economy

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he palm oil sector plays an important role in the Indonesian economy. In monetary terms, the value of Indonesia’s palm oil exports in 2017 stood at US$22.97 billion, up from $18.22 billion in the previous year.

It also has a political significance, as it is the source of employment for approximately 17.5 million Indonesians. It directly employs 5.5 million workers and indirectly supports up to 12 million workers. It also serves as the engine of economic growth in rural areas, lifting millions of Indonesians out of poverty.

In 1982, small-scale farmers only accounted for 2 percent of Indonesian palm oil plantation owners, as of 2016 the number had increased to 41 percent. By 2030 they are expected to account for 60 percent. But Indonesia’s most valuable export commodity is currently under immense pressure from the proliferation of discriminatory trade policies against palm oil.

Following a petition filed in February 2017 by the United States National Biodiesel Association, an ad hoc coalition of associations consisting of the National Biodiesel Board and 15 companies, the US Department of Commerce launched an investigation into biofuels coming from Argentina and Indonesia, following an allegation that both countries sold their biodiesel below “normal value”.

Based on the findings, the US Department of Commerce decided to impose anti-dumping duties on biodiesel coming from Indonesia ranging from 34.5 percent to 64.7 percent. The duties were further increased to a range of 92.52 percent to 276.65 percent in February. It is perhaps worth noting that two weeks prior to the ruling, the US Congress agreed to adopt a proposed tax credit for locally produced biofuels.

In June 2017, the Norwegian parliament adopted a resolution recommending the government exclude palm-oil based products from government procurements. On the surface, it looked like the decision was driven by environmental concerns. However, a closer examination would reveal that the motive behind the move was to make way for local producers to meet Norway’s national target of increasing the biofuel blend to 20 percent by 2020. It is also worth noticing that parallel to the adoption of the resolution, Norway constructed an ethanol plant to meet its national target.

Another example took place in March. In a bid to support locally produced vegetable oils, India decided to increase its tariff on crude palm oil (CPO) from 30 percent to 44 percent and refined palm oil from 40 percent to 54 percent, the highest in a decade. The tariff hike aims to narrow the price difference between palm oil and other locally produced vegetable oils, thus providing incentives for refiners to shift their purchases from palm oil to locally produced vegetable oils.

Against this background, Indonesian palm oil diplomacy should be directed at reversing discriminatory policies against Indonesian palm oil in major export destinations through exerting political pressure, creating public pressure and utilizing existing related international norms to stigmatize protectionist policies that hamper efforts to alleviate poverty.

In a democratic society, politicians or political systems are highly responsive to public opinion and thus tend to pursue policies that accord or appear to accord with the public’s wishes. To change anti-palm oil policies, therefore, Indonesian palm oil diplomacy should aim at deconstructing negative public opinion on palm oil.

Reflecting on the effectiveness of anti-palm oil campaigns by environmental NGOs, the Indonesian government should consider developing deep collaboration with NGOs that advocate for farmers’ rights in its palm oil diplomacy. One of the commitments under the 2030 sustainable development goals (2030 Agenda) is to end poverty in all its forms and dimensions by 2030 and farmers have been recognized as having critical importance in meeting this target. Indonesia can provide best practices in this regard.

External political pressure can give rise to policy change. Following the adoption of the European Union Parliament resolution that aims to ban imports of palm oil biofuel into the EU starting in 2021, Malaysia has issued an ultimatum to the United Kingdom that Malaysia might cancel a defense contract worth up to 5 billion pounds. Following this ultimatum, the UK government has since refused to make a statement on whether or not it will back the EU ban on palm oil in biofuels. This statement has also led the French government to issue a statement that it will oppose the EU ban on palm oil in a bid to secure defense contracts with Malaysia. Reflecting on the political pressure successfully created through Malaysia’s ultimatum, the Indonesian government should consider adopting similar measures.

Studies suggest that international norms can affect domestic politics. The environment is probably among the most conspicuous examples where international norms profoundly influence domestic policies. Following the adoption of the 2030 Agenda in 2015, the issue of deforestation has enjoyed the global limelight.

Under the 2030 Agenda, the international community is committed to halting deforestation by 2020. Since then, the international norm on fighting deforestation has got stronger and, as this paper has shown, been utilized as justification to advance national economic interests in some cases. Indonesia can use the same approach in advancing Indonesia’s national interests related to palm oil. In this regard, Indonesia can utilize existing international norms on poverty alleviation and small-scale farmers to raise policymakers’ awareness of the contribution of farming to alleviating poverty.

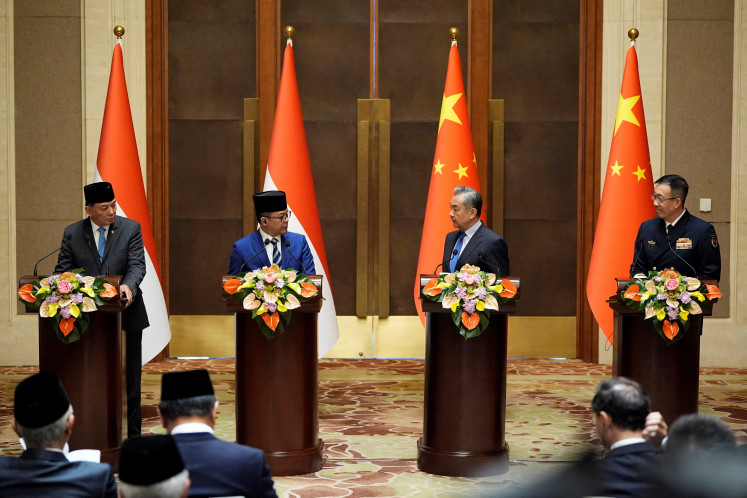

President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has issued strong statements on several occasions. During a G-20 summit in July 2017, President Jokowi met with leaders of European countries including the Netherlands, Spain, and Norway to express his concern over the unfair treatment of Indonesian palm oil.

The same sentiment was again expressed when President Jokowi urged the EU to end discrimination against palm oil during the ASEAN-EU Commemorative Summit on the 40th Anniversary of the ASEAN-EU Dialogue Relations in November 2017. The President’s strong statements should be followed up on by his Cabinet. Indonesia needs more assertive and tactful palm oil diplomacy.

______________________________

The writer works at the Directorate General of Multilateral Affairs at the Foreign Ministry. The views expressed are his own.