A person, not a caricature: Indonesia’s complex history of LGBT media representation

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

D

uring the Reform era, many Indonesians cherished depictions of LGBT characters on screen, however flawed their representations were.

Han, a 24-year-old member of the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community from Jakarta, has been taking particular note of her family and coworkers’ conversations lately.

These days, one person might ask “Why has there been a lot of LGBT stuff on TV and YouTube recently?” And the other might reply, “I know, right? It’s been trendy lately.”

Such comments sound strange to Han because depictions of LGBT characters have been part of Indonesian culture for years, whether in the 2007 drama Coklat Stroberi (Chocolate Strawberry) or the award-winning film and TV series Arisan! (The Gathering).

Han, who chose to use only her nickname for this story, realized, however, that few of the representations were truly empathetic toward her community, even in her favorite comedy variety shows like Extravaganza and Opera Van Java.

“We were all raised in a heteronormative society, so I had never thought that people like [late comedian] Olga [Syahputra] existed in real life without being laughed at or being comedic relief,” she said.

Han half-jokingly said she used to be homophobic and that she only now realized that what people found funny about many queer-coded characters in those comedy shows was their femininity.

“I was just not exposed to other LGBT representations growing up,” she added.

Butt of the joke

Filmmaker and critic Paul Agusta was not surprised by the tendency to frame LGBT characters as clownish or comical.

“It’s not just in Indonesia but in the history of cinema in general since way back when, it is a very easy joke to go to,” he said. “Because it’s considered very wrong for a male to want to behave in a feminine way or vice versa; it’s funny when it happens.”

But LGBT media representation in many countries has begun to change for the better along with growing public acceptance and understanding. Paul, who is a member of the LGBT community, however, has yet to see many of the changes in Indonesian media.

“I think the fact that Indonesia still hasn't moved on from those queer stereotypes – as being the butt of the joke – is a reflection of the national view that it’s still something wrong, deviant, to be ridiculed or laughed at,” he said.

“The question is, what does it indicate that we’re still portraying homosexuals or LGBT people that way?” he asked.

“There are still big media corporations, TV channels, newspapers publishing articles or news reports that label LGBT as sexual deviance or in other similar terms,” he said. “So if such portrayals are still being reinforced from the non-fiction side, don't expect any progress from the fiction side either.”

Rich history

Indonesia’s conservative turn over the last decade, as shown by stricter censorship and greater public backlash against social change, has limited LGBT representation on screen.

This change surprised writer, researcher and LGBT community member Nurdiyansah Dalidjo, who grew up with LGBT characters on Indonesian screens, big and small, from Betty in Betty Bencong Slebor (bencong is a derogatory term for gay men with perceived feminine characteristics), Emon in the beloved Catatan Si Boy films, to Karina in the 90s sinetron (soap opera) Si Manis Jembatan Ancol.

“Even though Betty Bencong Slebor came out in 1978, I knew as a kid growing up in the 90s that, as a collective, we Indonesians still remembered that movie fondly. And I think it’s a really good movie,” Nurdiyansah said.

Ben Murtagh, reader in Indonesian and Malay at SOAS University of London, also spoke about the abundance of Indonesia’s LGBT representation in his research, inspired by the 1988 film Istana Kecantikan (The Palace of Beauty).

“Sometimes these characters would be included in negative ways, sometimes in just curious ways,” he said.

But favorable depictions also arose, like in Arisan! and Coklat Stroberi, where the inclusion of LGBT characters conveyed that “there is a place, there can be a place, we can make places for us”, Murtagh said.

“Then suddenly, you’ve got 2014’s Selamat Pagi, Malam [In the Absence of the Sun], which is a much more nuanced, complex, realistic thinking of the difficulties of living in Indonesia [as a member of the LGBT community],” he added.

Some such depictions become a point of reference for others to abuse.

“Straight people used the name Betty to insult me back then,” Nurdiyansah said.

But he also recalled the time when the lesbian-couple-driven Berbagi Suami won numerous awards or when the late transwoman presenter Dorce Gamalama was hailed as a public figure and not bogged down by the term LGBT, which she thought had become politicized.

“In reality, in a lot of local communities here, queer friends have long had their places in our society, like Bissu people as spiritual figures, Burake people as blessers of paddy fields in Toraja, Warok and Gemblak people in East Java in the Reog Ponorogo dance performance,” Nurdiyansah noted.

“So homophobia […] is not part of our culture. It’s something alien, foreign,” he said.

Shift in power

When asked if she harbored resentment over the LGBT depictions in Extravaganza and Opera Van Java, Han appeared conflicted.

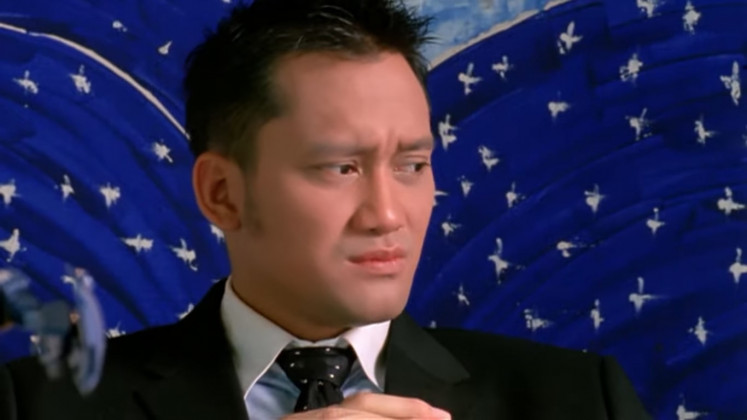

“With these kinds of depictions, I always remember Olga fondly in the sahur (predawn meal) shows. I really think of him as genuinely funny,” she said.

Han felt that people laughed not merely at his effeminacy but also because his jokes were hilarious.

Nurdiyansah felt the same way. “Such feminine gay or trans-leaning figures keep appearing [in media], be they [comedians] Aming, Olga or [the late] Ade Juwita. Yes, we can’t stay stuck in this stereotype that queer people are funny, that’s not fair. But every individual or community has their own coping mechanism to shift the power,” said the writer, who said he saw a bit of himself in these public figures. “We have the ability to turn those mockeries into laughter, and it’s okay for me, at least for me, as someone from the queer-gay community.”

“From that point forward, we have the access and opportunity to be there and be visible,” he added.

A few instances of LGBT representation on screen seem to have foretold Indonesia’s socially conservative turn in recent years, such as Madame X or Arisan! 2. The latter even opens with a demonstration scene against an LGBT film festival.

“Madame X is revolutionary in the various ways one could look at it – about a queer superhero or the representation of trans people in the movie,” Murtagh said. “But I think, looking at it now, it is the movie which seems to notice that, actually, things are not necessarily well in this post-reformation place,” he added.

“I guess [one] difference now is that there is a rise of streaming and digital space. [...] The question is, what local content can emerge that can actually reflect other possibilities of being LGBTQ other than what’s being offered by the mainstream?” Murtagh asked.

He believed the 2014 webseries CONQ, which has since been censored, was an example of good representation that could find its audience online by moving from one community to another.

Paul also stressed the importance of the fight against homophobia.

“Filmmakers will and must continue to make LGBT films. It’s necessary. It’s how we push for change. That’s how people are educated, through the media. But don’t expect it to be easy, don’t expect it to reach mainstream media unless it’s a controversy, just like what happened to Kucumbu Tubuh Indahku (Memories of My Body),” he said.