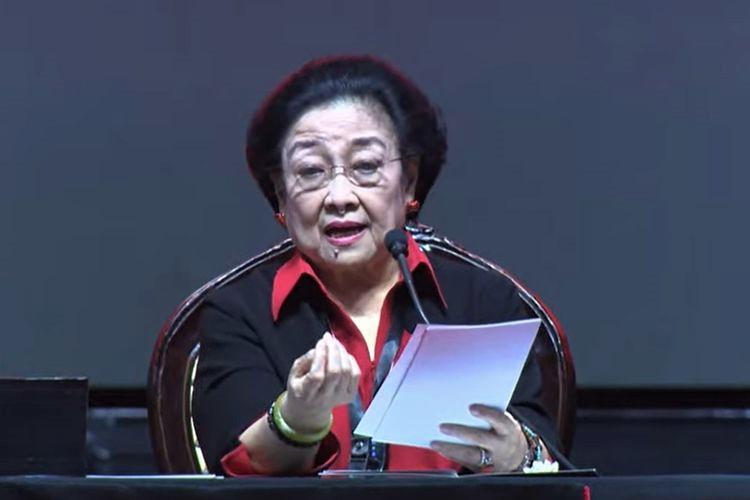

Megawati Soekarnoputri is at the center of Indonesia’s democratic conundrum

Megawati’s unchallenged authority in the party and favoritism for Puan are distant from the democracy that Indonesia wants to live in. These place her right in the middle of the country’s democratic conundrum.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

C

ounting down the months before the voting day in the 2024 presidential election, one key politician has yet to place her bet. She seems unperturbed despite the fact that others have coalesced into coalitions to field candidates for the race and insists on her own timetable toward this next chapter in her political leadership career.

For the 2024 election, it is widely known that she seeks to score a hat trick, a third time in a row winning the presidential and national legislative elections, after the 2014 and 2019 terms. If she were to succeed in her ambition, it would be a remarkable feat in Indonesia’s political history. Indeed, it would be a longevity and legacy to beat. Regardless of her tactics to achieve that goal, her long unbroken line of more than 30 years in politics marked by triumph and tribulations is historic.

Today, Megawati Soekarnoputri is the longest serving political leader in Indonesia, and her tenure encompasses highlights and low points in the nation’s political life. Only some 20 years after her father’s demise from the pinnacle of power did she begin consolidating the ideological spirit of Indonesia’s nationalism. She rose to the leadership of the Indonesia Democratic Party (PDI) only to have her standing vandalized by the New Order regime.

Rebuilding her movement as one of key opposition forces to the regime, she led her party to win a third of the votes in the first open election in 44 years. Becoming the president in the middle of political turmoil, she continued to insist on constitutional and democratic order by opening direct election for executive positions, including the presidency. Losing in two presidential elections herself, she nonetheless built the party to remain the leading political movement in the country. The 2014 and 2019 elections are the testament of such tenacity and resilience.

There are several insights one can draw from this trajectory and which could be imperative for future politics in the country. First is the insistence on constitutional order, that politics must be within a formal and legal framework, rather than just an expression of power. Second, and of no less importance, is Megawati’s conscious embracing of secular and even leftist segments of the political spectrum, as well as ethnic and religious minorities.

Third is her understanding of the intimate sociocultural contexts of national politics, as well as leveraging her Javanese origin. She has forged a tie with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the traditionalist Islamic organization that is critical in establishing a majority.

Many might have overlooked Megawati’s far-reaching political influence with her sometimes mocking media coverage. Several of her controversial statements on current issues have caused her to go viral in news cycles but have never heavily impacted her standing. Her simple designation with the honorific Ibu in the national political parlance is further evidence that her role extends beyond her own formal attribution as a party chairperson.

With such highlights, however, her longevity could also make her nearly irreplaceable as the leader of such a pillar of Indonesian politics, creating a great challenge for the next generation and placing her at the center of the country’s democratic conundrum.

Her ambition for an electoral hat trick is a clear reflection of her belief in constitutional order. It underscores that to achieve such a record, the path is nothing other than to follow the rules set out in the 1945 Constitution, which stipulates a regular five-year election for the presidency and the legislative body. This is consistent throughout her political trajectory, work through and building formal institutions. From the early days in a political party under an authoritarian government, through to constitutional and electoral reforms, through the presidency and continuous political contestation.

When in recent times discourses from President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s supporters to extend the current presidential tenure to more than a five-year term or to allow him to run for a third term were promoted, it was her and PDI-P that opposed these strenuously. It is her legacy to open and regularize presidential elections, regardless of who wins. She lost twice in this framework, and it was not herself – but a cadre in her party – that won the presidency twice. For her, this constitutional order must hold.

Furthermore, her politics follow in the footsteps of Sukarno, to embody the diversity that is Indonesia, consciously acknowledging those in the nation who are from ethnic and religious minorities and who are secular or nationalistic in their politics. Her party is even open to those who are in the left of politics, those who were demonized by the New Order.

The nationalism under this Sukarno stream is indeed espousing the notion of one nation, but rather than promoting one ethnicity or religion or ideology, it strives to include the hundreds of sociocultural identities and ideologies among the diverse population of the archipelago.

In recent elections, clearly people in ethnic and religious minorities voted overwhelmingly for the PDI-P and its candidates. In Bali, Minahasa, Batak, Nias, NTT, Maluku and Papua, the PDI-P is the embodiment of their voices. In policies and politics, she endorses a more secular streak, and strong criticism of religious radicalism citing Islamists’, such as the Taliban’s, treatment of women.

Despite counter-criticism from conservative Muslims, she is steadfast in criticizing women who frequently attended religious events rather than attending to their household or pursuing work.

On building a strategic alliance, she learned early from her father that despite their humble appearance, the Nahdliyin, members of the NU community, are the “fighters for the Indonesian nation”. In her struggles during the New Order times, she was close to Abdurrahman “Gus Dur” Wahid, the leader of NU and pro-democracy activist. Despite their rift in early years of post-Suharto era, the relationship, now with Gus Dur’s family and successors, endures.

Ideologically, her secular nationalist sentiments and NU’s traditional Islamic stream are fellow travelers in the nation’s political path, perhaps because both arose from the Javanese tradition that allows them to share common experiences, socially, economically and culturally.

In politics, she has shared the national platform with leaders of NU. Her vice president, Hamzah Haz, and her running mate, Hasyim Muzadi, were prominent Nahdliyin. Fast forward to 2019, she later revealed that it was she who told Jokowi to pick Ma’ruf Amin, the supreme leader of NU then, as his running mate. It proved to be decisive in that election with overwhelming numbers in both Central and East Java, both home to the PDI-P and NU. This coalition works electorally, and she might repeat this by engaging with the Gus Dur family and the wider NU community for 2024.

She is, though, the supreme leader of the movement, of the party and is, at this point, irreplaceable. She holds the ultimate power in the organization with minimal oversight or challengers. None in the party could come even close to have her persona or pedigree to sway the millions of loyal followers. Even Jokowi, who won the presidency twice with the endorsement of Megawati, would not be able to count on support from the die-hard members without her backing.

Puan Maharani, her daughter, followed into politics and has taken an apprenticeship toward the leadership, first by running and winning a parliamentary seat, then by moving up the ranks to become the party leader in the legislature. She then took a stint as Joko Widodo’s minister for human development. In 2019 she returned to the House of Representatives and served as the speaker. However, she lacks the key credential of the second “P” in PDI-P, perjuangan (struggle). Unlike Megawati who held the movement together against an oppressive regime in the 1980s and 1990s. Her survey numbers for the presidential election hover in low digits.

Megawati’s unchallenged authority in the party and favoritism for Puan, however, are distant from the democracy that Indonesia wants to live in. These place her right at the center of the country’s democratic conundrum.

Perhaps Megawati’s insistence on holding the announcement of PDI-P’s presidential candidate is to bide her time for Puan to be able to consolidate enough party grassroots, die-hard support for her to serve as the next chair of the party. Meanwhile, for Megwati to achieve the hat trick, at this point the path is with one of PDI-P’s leading members, Central Java Governo Ganjar Pranowo.

No doubt Megawati Soekarnoputri is a pivotal figure in our politics who has at many critical junctures shaped the country’s constitutional and governance framework. Her belief has held not just her party but the nation together. However, her reality also puts our democratic future in limbo.

***

Adi Abidin, a research fellow at Populi Center, and Charine Pakpahan are consultants at IndoVibrant Strategic Advisory. The views expressed are their own.