Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsA legal review of the 'sink the vessel' policy

President Joko ââJokowiâ Widodoâs recent statements in favor of sinking foreign vessels suspected of illegal fishing arouses not only support but also critical questions

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

P

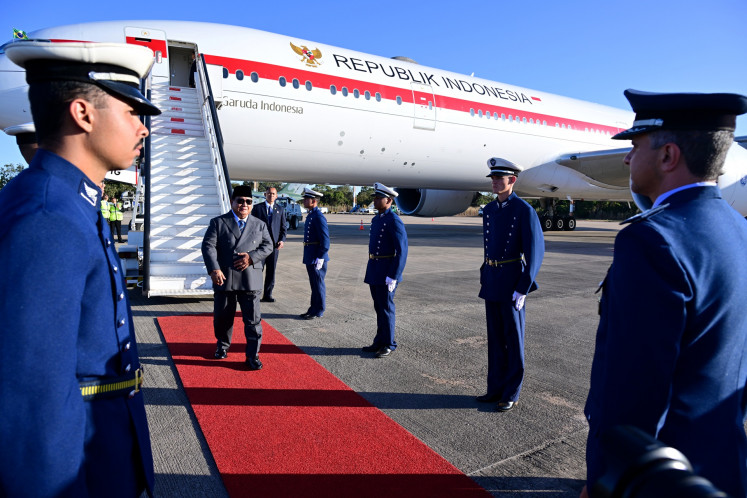

resident Joko ''Jokowi' Widodo's recent statements in favor of sinking foreign vessels suspected of illegal fishing arouses not only support but also critical questions. Chief among the questions is the legality of such a policy and whether it contradicts the 1982 United Nations Conventions on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to which Indonesia is a signatory.

Before engaging in a discussion of legality, let us first discuss the background of the policy. To begin with, the 'sink the vessel' remark was a quick response to the finding made by the current Indonesian Marine Affairs and Fisheries Minister Susi Pudjiastuti.

The finding was so chilling that a swift deterrent action seemed needed. The finding discovered that at a certain time on a certain day, over 70 vessels of 50 to 70 gross tonnage entered Indonesian waters.

These vessels were not under the ministry's vessel monitoring system and were therefore suspected of conducting illegal fishing activities.

It is estimated that the loss sustained specifically at that certain time of day in a certain area of

Indonesian waters was close to US$1 million.

That sum rises to nearly $100 billion in annual losses from illegal fishing in Indonesia, based on the ministry's official research.

For a newly transformed maritime state that will rely heavily on maritime-related resources, such losses are simply not acceptable.

Accordingly, the policy was introduced to curb illegal fishing practices in Indonesia. Coordinating Maritime Affairs Minister Indroyono Soesilo underlined the legal basis relevant to the policy, i.e. article 69, paragraph 4, Law No. 45 2009 on fisheries.

According to the article, subject to sufficient preliminary evidence, Indonesian authorities may burn and/or sink foreign vessels suspected of illegal fishing in an Indonesian fishing management area. The article, though, lacks a definition of Indonesian fishing management areas, which could create legal issues with the UNCLOS.

The UNCLOS classifies seas into zones, each with its respective recognized rights. The rule of thumb with UNCLOS zones and rights is that the farther from the coast the lesser the rights. Indonesia, as an archipelagic state, has full sovereignty over her territorial sea, internal waters and archipelagic waters.

The lesser rights or sovereign rights cover contiguous zones, exclusive economic zones (EEZ) and continental shelves.

There should be no question that the policy is intended for foreign vessels suspected of conducting illegal fishing within the zones where Indonesia has full sovereignty.

In fact, as a matter of law, pursuit into other sea zones is allowed for alleged violations taking place in fully sovereign waters.

Legal questions arise if alleged illegal fishing carried out by foreign vessels takes place in zones of sovereign rights, such as EEZ. Article 73 of the the UNCLOS clarifies what measures may be taken to enforce laws and regulations by the coastal state in EEZ and they do not include the sinking of vessels.

Under the UNCLOS regime, enforcement in EEZ may include boarding, inspecting, arrests and judicial proceedings. Penalties thereof may not include imprisonment and other corporal punishment. Even bonds or security for prompt release of arrested vessels and crews may be reasonable.

What may become a hurdle for Indonesia in implementing the policy is the prompt release obligation governed in paragraph 2 of article 73 of the UNCLOS. Referral to article 292 concerning prompt release of vessels and crews elaborates the possible mechanism should a dispute arise between a flag state whose vessel is being detained and a coastal state.

The flag state and coastal state are given ten days from the time of detention to choose their forum. Failure to do so will automatically revoke the application of forum selection under article 287 of the UNCLOS. Given that Indonesia has not made any declaration under article 287, unless otherwise decided, arbitration will be deemed as the forum.

The next issue is not so much about Indonesia's record in international dispute settlement as the trend of case law concerning prompt release obligations.

At the moment, Indonesia's involvement in international dispute settlement is not impressive. Perhaps the hardest lesson Indonesia has had to learn with regard to international dispute settlement was that of the 2002 Sipadan-Ligitan case when the International Court of Justice rejected Indonesia's claim.

Another occasion with a similar outcome was the 2000 Karaha Bodas case where the arbitral tribunal fined Pertamina, a state-owned company, a substantial amount of money as a consequence of its unilateral breach of contract. Pertamina's foreign bank accounts are currently still frozen.

In the WTO mechanism, as of October 2014, Indonesia has been involved in 32 cases, either as complainant, respondent or third party. Over half of the cases submitted were ruled against Indonesia. The list could go on but the big picture is clear.

Moving to the trend of case law pertaining to prompt release obligations, decisions of the International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) may serve as a useful reference. As of 2005, of seven prompt release obligation cases that have been submitted before ITLOS, five were decided in favor of prompt release of the detained vessels.

Nevertheless, all hope is not lost. Indonesia can still achieve a deterrent effect by increasing the amount of bonds for prompt release and penalties afterwards.

In increasing the sum required, consideration, as ITLOS case law suggests, should include the seriousness of the alleged offences, the penalties under the law of the coastal state and the value of the vessel and cargo.

In conclusion, the 'sink the vessel' policy is permissible for alleged activity in Indonesia's territorial sea, internal waters and archipelagic waters. As for illegal fishing in EEZ or other sovereign rights zones, Indonesia is under the obligation to follow the UNCLOS mechanism.

_______________

The writer, who obtained his doctorate degree in international law from The Maurer School of Law, Indiana University Bloomington, works for the Foreign Affairs Ministry. The views expressed are his own.