When geopolitics and inflation mix: A 1970s throwback?

Between fiscal and monetary policy, fiscal policy is likely the more effective tool to mitigate stagflation-type pressure and fiscal deficits are likely to widen.

Change Size

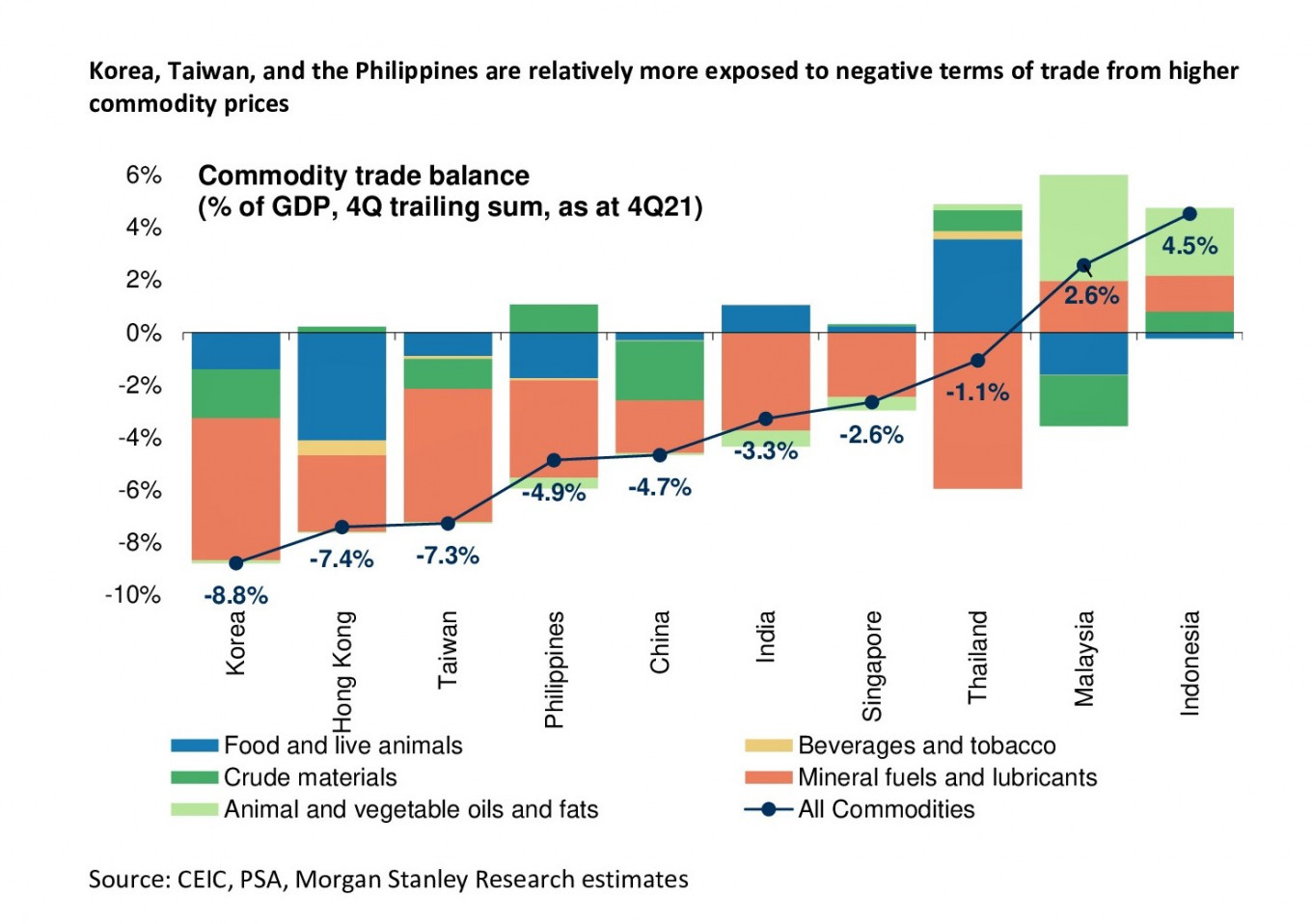

Asia's exposure to negative terms of trade from higher commodity prices. (Courtesy of/Morgan Stanley).

Usage: 0 (Courtesy of/Morgan Stanley)

Asia's exposure to negative terms of trade from higher commodity prices. (Courtesy of/Morgan Stanley).

Usage: 0 (Courtesy of/Morgan Stanley)

R

ecent geopolitical tension presents risks of an exogenous shock. The 1970s energy crises are salient examples of exogenous supply shocks. Back then, energy disruption led to cost-push inflation and crimped spending and profitability.

Central banks such as the Fed also tightened aggressively to rein in inflation expectations which had come unanchored from prior loose policy. The upshot? A slowdown.

Hence the key debate now is – to what extent do geopolitics pose upside risks to inflation and downside risks to growth for our coverage economies in ASEAN, Korea and Taiwan? Could policy overtighten and growth cycles turn South?

The trade linkages our coverage economies have with Russia and Ukraine are not high. Inflation is one key conduit through which geopolitical tension would be acutely felt.

Inflation has been hit by a multitude of shocks in past years, from COVID-19 production disruption, decarbonization and a decline in labor force participation rate. Geopolitical tension now poses further upside risks.

This would come through a rise in energy prices which could also have spillover impact on production of energy-intensive segments, such as metals and fertilizers. We are also watching the price rise in agricultural products as well as metal commodities and other elements.

Apart from the rise in prices, these elements are also important components for manufactured products such as semiconductors and transport equipment and construction. Hence, supply shortages would have spillover implications on these economic activities.

Food and energy items are important inflation drivers. Commodity inflation has accounted for a substantial part of the rise in inflation in our coverage economies so far. We calculate every 10 percent rise in food and energy items alone would add 0.9-4 percentage point to headline consumer price index (CPI) from first-round impact, all else equal.

The Philippines and Thailand are the economies most exposed to upside inflation risk from food and energy prices. Meanwhile, Korea, Taiwan, and the Philippines are relatively more exposed to negative terms of trade from higher commodity prices.

Fiscal policy can help to provide some cushion against upside risks to inflation and downside risks to growth. Between fiscal and monetary policy, fiscal policy is likely the more effective tool to mitigate stagflation-type pressure and fiscal deficits are likely to widen.

We calculate every 10 percent rise in energy and food prices could increase spending burden by 2 percent of gross domestic product. This is not insignificant but there’s fiscal room to offset this. Public debt to GDP has risen during the COVID-19 pandemic but still stand at manageable levels between 33 percent and 66 percent of GDP for most of the economies under our coverage, suggesting room for the public sector to lever further if necessary.

On funding, most of these economies are still running a current account surplus, meaning there is excess savings at home to fund wider fiscal deficits.

On that note, the energy subsidy scheme in Indonesia (and to some extent, Malaysia) has led to debate about whether rising oil prices could create fiscal stress, which could cascade through to inevitable retail fuel price hikes and hence to inflation and monetary policy.

Rising oil prices increase the energy subsidy burden. However, commodity-related government revenue have also been growing strongly given Indonesia's status as a net commodity exporter. Indonesia's non-tax commodity revenue and oil and gas income tax revenue rose around 55 percent-60 percent year-on-year in 2021. To the extent to which non-oil commodity prices have risen even more than oil recently, we believe the fiscal pressure is likely manageable still.

However, a sustained sharp rise in oil commodity prices in itself and also relative to other non-oil commodity prices is what could pose fiscal risks. This is because the rise in oil subsidy burden could then get nonlinear as a widening gap between market price and subsidized price increases arbitrage activities and that outpaces the commodity revenue growth from elsewhere.

On monetary policy, with growth lower but recovery still intact, we expect central banks in our coverage region to continue with policy rate normalization to lean against inflation pressure. However, we think the aggressive tightening seen by the Fed in the late 1970s and early 1980s is unlikely in our coverage economies.

In this context, monetary overtightening is unlikely to be what pushes the growth cycle to turn south in our view for our economies.

We note that unless it is expected to lead to second-round inflation from healthy demand, central banks typically do not respond to supply-side inflation as monetary tightening cannot solve supply-side constraints. To this point, most of the economies we cover are still running a negative output gap. This is likely why demand-pull inflation still looks manageable.

Besides, for those economies which are more advanced in the recovery path, central banks (e.g. Bank of Korea and Monetary Authority of Singapore) have already embarked on policy rate normalization last year ahead of the Fed. This buys them flexibility when it comes to managing inflation pressures, reducing the likelihood of knee-jerk tightening.

In addition, for central banks which focus on currency stability, such as BI, higher foreign reserves buffer, higher real rates differentials vs. the United States, and positive commodity terms of trade help to buy protection against capital volatility, lessening risk of disruptive tightening.

Overall, our base case is for our coverage economies to transition from a “Goldilocks” to “steady-state expansion” phase in 2022. In this steady-state expansion phase, growth is likely to broaden from exports to domestic demand, inflation is likely to rise without getting out of hand and policy rates would normalize further without being disruptive for the growth cycle. However, growth is certainly lower and inflation higher than what we had envisaged before given the geopolitical tension.

As geopolitics linger, we think economies that offer a stagflation hedge and domestic demand buffer are likely better placed. We see two groups amongst our coverage economies.

The first group consisting of Indonesia, Malaysia, and the Philippines are those which offer a stagflation hedge and/or a domestic demand buffer. Indonesia and Malaysia are the only two net commodity exporters in our region. The Philippines is exposed to negative terms of trade shock but is relatively insulated from the second-round spillover from slower global demand/tighter financial conditions. Meanwhile, Group 2 consisting of Singapore, Thailand, Taiwan, and Korea are more exposed to negative terms of trade from higher commodity prices and spillover from trade/financial linkages.

***

The writer is a managing director in the Morgan Stanley economics research team.