Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe Last Man in Waluya Sejati Abadi

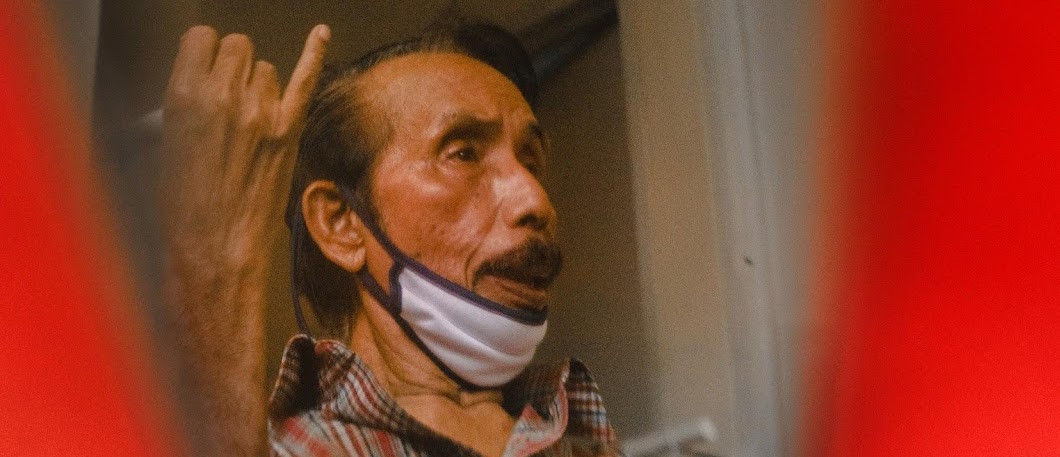

He is the last man standing in a nursing home dedicated to former political prisoners. But Lukas Tumiso doesn’t want your pity as he discusses perseverance, scandal and survival in the first of this two-part story.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Part 1. Regaining life

Lukas Tumiso refuses to mourn the things he’s lost. He has left remnants of better days around him, pictures and books from a faraway time, reminders of his desire to carry on. They sustain him in this difficult time. “There were 27 of us here, and another 54 on the waiting list,” the 81-year old said. “But one by one they passed away, and now I’m the only one left.”

Panti Waluya Sejati Abadi, the nursing home where he lives, has been deserted for over a year. All its residents have either died or moved away during the pandemic, leaving Lukas alone. No nurse checks on him, no staff ensures his safety. But the paint is new, the roof recently fixed and the smell of freshly cooked lunch lingers in the kitchen. Neighbors drop by almost every hour, exchanging pleasantries and food. There is life in this building.

Initiated in 2004, Waluya Sejati Abadi was set out to be a safe haven for former political prisoners who fell into hard times in their old age. Specifically, those whose lives were turned upside down by the 1965-66 massacre of suspected Communist sympathizers, which left millions dead and scores more jailed, sent to forced labor camps, and disenfranchised for life.

Nestled in a small neighborhood in Senen, Central Jakarta, Waluya Sejati Abadi was a treasure trove of stories from a part of Indonesian history many would rather forget. It was home to former party agitators, jailed activists and hardened survivors. Like an army of fabulists, they would regularly host researchers, activists and curious students. Telling their story was a way of preserving themselves in eternity.

Lukas was among them. Once a respected school teacher, his membership in a youth organization with suspected links to the now-defunct Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) landed him in hot water. He was arrested in 1969 and sentenced to indefinite exile in the forced labor camp in Buru, a remote island near Sulawesi. He stayed there, his fate uncertain, for 10 long years.

In Buru, he struck up a lifelong friendship with fellow inmate Pramoedya Ananta Toer, a celebrated author arrested for his membership in the leftist cultural organization LEKRA. Upon Lukas’ release in 1979, he smuggled the manuscript of Pramoedya’s magnum opus, Bumi Manusia (This Earth of Mankind), in the folds of his ragged luggage. The book shook Indonesian society to its very foundations, and the rest, as they say, is history.

He tends to the nursing home’s gardens, fixes its roofs, and is reorganizing its book collection. (JP/Eandaru Kusumaatmadja)But these are things he’s spoken about before. His friendship with Pramoedya has afforded Lukas the status of a minor celebrity, leading to visits from journalists and eager film producers. He has spoken many times about the squalid conditions in Buru and the atrocities committed against the people held there. Today, after a year of solitude, he tells me he wants to talk about something different.

“I want to talk to you about what happened after Buru,” he insisted. “I want to talk about how I regained my life.”

Wild days

In December 1979, Lukas arrived in his hometown, Surabaya, to find his life in tatters. His exile had left him financially ruined. His teaching career was effectively over, as former political prisoners were barred from taking jobs in official institutions. To make matters worse, his wife had left him, marrying a powerful police officer and taking their child.

Lukas was convalescing in a distant relative’s home when he heard a car horn bellowing outside the gates. “A hardtop jeep was parked outside the house, surrounded by children,” Lukas recalled. “An entourage of bodyguards stepped off the car, then a face I faintly recognized. The neighbors started screaming, ‘It’s Djalal!’”

The man in question was a celebrity in Surabaya, a comedian who had risen to fame as co-founder of the troupe Surya Grup and starred in hit movies. But a long time before all this, Djalal was an awkward middle school student who studied under Lukas. The comedian’s visit, though, was motivated by more than a desire for nostalgia.

“He confided in me that his father-in-law had also perished during the massacre,” Lukas said. “This made him feel compelled to help me. He spoke to my family and asked to take me in.”

Lukas was invited to stay at Djalal’s mansion and followed his former pupil around as he starred in stage plays almost every night. One time, while on the way to a performance, Djalal noticed his teacher’s melancholy state and decided to take a sudden detour. To Lukas’ horror, they pulled into Surabaya’s infamous red light district, Dolly.

“‘Look, sir, just stay here while I work. I’ll pick you up around 3 in the morning,’” Lukas said, mimicking Djalal. “I was shocked. PKI members weren’t allowed to smoke and gamble, let alone party with prostitutes.” His former pupil let out an outrageous laugh, and remarked: “Sir, the communist party is dead. I personally disbanded them. Now go and have fun.”

Lukas recalled how Djalal conspired with the proprietor of Dolly’s most decadent brothels and asked them to “entertain my guest.” After 10 austere years in exile, suddenly Lukas was living large. “Djalal would give me money every morning, then take me to Dolly at night,” Lukas said. “He picked the girls and bought the drinks.”

His dream is to return to Buru, where he spent ten years in exile, to restore the graves of political prisoners who died there. (JP/Eandaru Kusumaatmadja)For three months, Lukas partied like a king. “Eventually I realized this couldn’t go on,” he said. One day, while Djalal was out, he borrowed his motorbike and drove around Surabaya, seeking old friends from his days before exile. He found many struggling to survive, burdened by their politically controversial past. “Some took odd jobs, some fixed furniture, some became bicycle mechanics. I couldn’t bear to see it.”

He returned to Djalal and asked for money to start a materials shop with a former prisoner he met at Buru. Within a few years, the business was thriving. “I was overseeing deliveries during the day but still returning to Dolly at night,” Lukas said, laughing. After a rift with his business partner, though, he left the store and became a freelance gardener and landscaper.

Even though he had some measure of stability, Lukas was far away from his true passion: teaching. No school would hire a former political prisoner like him, and there was no way to hide his past. During the New Order Era, former political prisoners and their families were forced to carry special identification cards and report each month to the nearest local military command.

During one of these visits, Lukas spotted a group of kids studying and got an idea. “A senior PKI leader, Njoto, once said to us, ‘If you’re a bandit on the run, hide near the police station. That’s the last place they will look.’” Lukas recalled. “He was right. Constantly hiding wore me out.” He gathered his courage and approached the students, asking them if they had any difficulties.

They nodded, confiding in him that they were failing at math. Sensing an opportunity, Lukas wowed them with his knowledge and walked away. The students, all children of local military personnel, began chatting with each other about the mysterious tutor who would visit every month and magically solve all their academic woes.

Eventually, they took the bait. “One day, a high-ranking member of the military command approached me,” Lukas said. “‘What did you do to my kid?’, he asked. ‘He was flunking math, then he improved, and he said it’s because of you.’ To my surprise, he was not there to arrest me. He wanted to ask me to tutor his son!”

Ever the streetwise urchin, Lukas pretended to have doubts. “I said I didn’t want to get arrested, and he immediately guaranteed my safety.” Realizing he was in a position to negotiate, Lukas countered with a bold offer: he wouldn’t risk arrest just for one child. If the military man wanted his kid taught, he would have to find 11 other students. To his surprise, the soldier agreed.

His small class was the makings of a newfound career as a private tutor, a role he took on for two decades. He had regained his passion, became financially stable and rebuilt his life from the ruins of exile. Then came a call from an old friend, his past returning to collect dues.

Part 2 to be published tomorrow.