Q&A: Under the shady Indonesian rain forests

Not only forests, Indonesia also has vast amounts of peatlands, which also form the floor of rain forests. There are roughly 22 million hectares of peatlands in 2010, equal to 5% of the global peatland area. Peatlands cover around 3% of the globe, but store one third of the total global soil carbon. It was estimated that in 2010, Indonesian peatland stores 132 gigaton of CO2. In comparison, the world’s largest rain forest, the Amazon, stores 168 gigaton of CO2.

Change Size

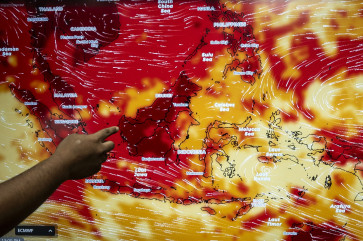

The El-Niño effect: Officers spray water on forest fires in a concession area in Tulung Selapan, Ogan Komering Ilir, South Sumatra, on Oct. 28. Millions of hectares of forest and peatland in Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Papua have caught fire during the prolonged drought. Major landslides and floods are looming for Indonesia as the archipelagic nation prepares to enter the rainy season at the end of this month. (JP/Jerry Adiguna )

The El-Niño effect: Officers spray water on forest fires in a concession area in Tulung Selapan, Ogan Komering Ilir, South Sumatra, on Oct. 28. Millions of hectares of forest and peatland in Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi and Papua have caught fire during the prolonged drought. Major landslides and floods are looming for Indonesia as the archipelagic nation prepares to enter the rainy season at the end of this month. (JP/Jerry Adiguna )

I

ndonesia is under constant criticism for failing to protect its rain forests. Each year, the rate of deforestation is accelerating, due to illegal logging and forest burning. What is actually happening? Why is it so hard for Indonesia to preserve its rain forests?

Why Indonesian rain forests are important?

Indonesia’s rain forests are the third largest in the world, just after Amazonian rain forest in South America and the Congo Basin in Africa. Aside from the rain forest in Borneo (also known as Kalimantan), Indonesia also has a vast area of rain forest in Sumatra and also in Irian (Indonesian side of Papua).

Not only forests, Indonesia also has vast amounts of peatlands, which also form the floor of rain forests. There are roughly 22 million hectares of peatlands in 2010, equal to 5% of the global peatland area. Peatlands cover around 3% of the globe, but store one third of the total global soil carbon. It was estimated that in 2010, Indonesian peatland stores 132 gigaton of CO2. In comparison, the world’s largest rain forest, the Amazon, stores 168 gigaton of CO2.

What is happening to Indonesian rain forests?

Massive deforestation from land conversion, illegal logging, and forests burning. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization estimated that Indonesia lost 1.87 million hectares of forest a year from 2000 to 2005, roughly the same size as Portugal.

A 2014 study published in the Nature Climate Change journal revealed that Indonesia has succeeded in overtaking Brazil in term of highest rate of annual loss of primary forest. 16 million hectares of forest were lost within 12 years from 2000, 38% was primary forest, a very important part in carbon storing and biodiversity, which should be preserved.

Another significant issue is the forest burning, which has happened annually in Indonesia since the mid-1990s. However, in 2015’s environmental disaster, which spread toxic haze as far as Malaysia and Singapore, most of the fires were started deliberately to clear peatland for agriculture such as palm oil plantations. Global Forest Watch Fires calculated that more than half of the fires occurred in peat area.

Papua has also suffered from haze and forests burning. Greenpeace Southeast Asia, which monitored 112,000 hot spots from Aug. 1 to Oct. 26 2015, also found that 10% out of these hotspots were in Papua, where never have fires of such scale occurred before. These fires have a strong correlation with a large agriculture project, Merauke Integrated Food and Energy Estate (MIFEE), covering a 1.2 million hectare area, or a quarter of Merauke.

What is the impact of forests fire?

The World Bank has estimated US$16 billion in economic costs from the fires in 2015, more than double what was spent on rebuilding Aceh province after the 2004 tsunami. The areas affected most were Sumatra and Kalimantan.

Global Fire Emissions Database calculated that the daily emission from the fires exceeded the daily emission of the entire US economy, which is 20 times larger than Indonesian economy. The emissions from forest fires is certainly an obstacle to former Indonesian President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s pledge to reduce its carbon emission by 26% by 2020.

The National Disaster Mitigation Agency (BNPB) stated that the haze crisis resulted in more than 500,000 people in six provinces suffering from acute respiratory infections. A Greenpeace study found that smoke from fires kills an estimated 110,000 people every year across Southeast Asia, mostly as a result of heart and lung problems, and weakens newborn babies. Orangutans, already an endangered species, are also threatened and forced to flee their habitat due to the fires.

Who is responsible for the deforestation?

Pulp and paper companies and the palm oil industry are often blamed for the problem. Another culprit is the rampant practice of illegal logging. Data from World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) shows that 40-61% of Indonesian timber production comes from illegal logging.

Have these companies been punished?

In relation to 2015’s forests burning and haze crisis, seven corporate executives were arrested in September 2015. Among these arrests was a senior executive from PT Bumi Mekar Hijau (BMH), a unit of Singapore-based Asia Pulp and Paper (APP), which is also Indonesia's largest pulp and paper producer. Later in December, 23 more companies were punished, most of which are pulp wood and palm oil plantations operating on Sumatra and Borneo islands. Three companies shut down as their licenses were revoked, while the licenses of 16 others were suspended and four companies were placed under close observation.

However, Palembang District Court in South Sumatra made a decision to reject the lawsuit filed in 2014 by the Environment and Forestry Ministry against Bumi Mekar Hijau. The lawsuit demands BMH to pay 7.8 trillion rupiah (US$540 million) to the state for damages from burning land. The court rejected the decision on the basis that the evidence collected in the case against BMH failed to prove its alleged criminality in the burning of 20,000 hectares of its concession in Ogan Komering Ilir, South Sumatra, in 2014. Furthermore, BMH was still able to plant acacia trees on its concession after it was burned, which according to the court meant there must have been no environmental damage.

Indonesian Forum for the Environment (Walhi) South Sumatra chapter director Hadi Jatmiko said that the reasoning behind the verdict was illogical. 'Environmental damage shouldn't only be seen from the damage to land. The fire caused the Air Pollution Standard Index [ISPU] to reach a hazardous level and that's enough to prove that there was environmental damage,' said Hadi.

The failure of this lawsuit made Walhi also question the future result of other cases.

Why can’t the Indonesian government stop the deforestation?

A 2015 report by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the Government of Indonesia shows that Indonesia has a relatively weak forest governance system, scoring only 35.97 out of 100.

An international environmental forum has also found that Indonesia still lacks the necessary legal basis to support zero-deforestation commitments. Law No.39/2014 on plantations, for instance, requires palm oil companies to use all their permitted land to plant oil palms, leaving them unable to allocate any of their land for conservation purposes. Another is the plan from the Trade Ministry to relax regulations for timber export, which aimed to boost Indonesian exports but was criticized for enabling illegal logging. The plan was canceled after the ministry received feedback from the European Union, the Environment and Forestry Minister and NGOs. Nevertheless, the plan showed inconsistency from various actors in government to protect Indonesian rain forests.

Illegal logging mainly happens due to the lack of law enforcement in the region. Regional governments and officers are bribed to open the forests or not to report the logging. A study by the Corruption and Eradication Commission (KPK), published in October 2015 found that state losses from missing potential non-tax state revenue in the forestry sector between 2003 and 2014 amounted to Rp 86.9 trillion (US$521 million), or Rp 7.24 trillion per year.

Transparency is indeed a big problem. The Environment and Forestry Ministry was criticized by Forest Watch Indonesia (FWI) due to its secrecy. The Ministry responded only to 127 out of 915 information requests during 2014 to 2015. FWI director attributed this lack of transparency to be the main cause of deforestation, as shown by an analysis done by the Indonesian Center for Environmental Law.

Can the government just forbid people to cut down forests?

The government of Indonesia has introduced a two-year forest moratorium since 2011, which stopped the Forestry Ministry to grant new permits for companies operating in primary forests and peatlands. This moratorium was issued following the bilateral agreement with Norway in the context of REDD+, in which Indonesia will receive funding as large as US$1 billion if it succeeds to protect its forests.

Moratorium does not completely stop deforestation, as it does not affect existing licenses given prior to the moratorium.

Despite protests from the Indonesian Palm Oil Association (Gapki), the moratorium was extended for another two years in 2013. On the other hand, the extension was welcomed by many, including the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) and Indonesian Conservation Community (KKI). KKI had previously urged the government to extend the moratorium, stating that the first period was not effectively used ‘to straighten up the chaotic state of forestry permit issuance,' and produced a single map on forests.

In 2015 the moratorium was extended again. Responding to the demand to include secondary forests under protected areas, Ruandha Agung Sugardiman, the Environment and Forestry Ministry's director general of forestry planning and environmental governance, argued that, ‘there will be no more production while at the same time there is a demand for us to increase production.’

Following the 2015’s haze crisis, Jokowi stated that no more licenses for peatland concession would be given. This means that no more peatlands can be converted for other uses, including for palm oil plantations. A finding by Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR) reveals that peatland conversion, which include draining of peatlands, is the main cause of the haze crisis.

In November, Vice President Jusuf Kalla confirmed the plan would restore at least 2 million hectares of peatland in the next five years. However, the newly established Peatland Restoration Agency (BRG) must depend on donations to run its operations in seven provinces, as it has not been included in the 2016 state budget.

Is there any effort from the palm oil companies to helping save Indonesian forests?

There is actually a global body named Roundtable of Sustainable Palm Oil (RSPO), with Indonesia being a member. RSPO has a certification to ensure the sustainability of the product, verifying that the palm oil comes from plantations that are harmless to the environment and local communities. However, RSPO certification system does not work perfectly in its implementation because some big companies still buy palm oil from suppliers with unsustainable business practices. Last year, RSPO announced a plan to make tough new sustainability standards under broad criteria that include bans on deforestation, fires and peatland planting as well as rules relating to carbon emissions, human rights and transparency.

Actually, palm oil producers in Indonesia had made a bold pledge for zero deforestation. Indonesia Palm Oil Pledge (IPOP) was announced in September 2014 at the UN General Assembly, signed by five palm oil giants, who account for 80 percent of the country's palm oil production. However, IPOP was opposed by the Indonesian government.

Coordinating Maritime Affairs Minister Rizal Ramli stated that the pledge was against the principle of sovereignty, since it was made by companies and as a response to other countries demand for more sustainable palm oil. The view was mirrored by The Environment and Forestry Ministry's director general of planning, San Afri Awang. The Office of the Coordinating Economic Minister also argued the pledge would jeopardize the country's palm oil industry, currently the biggest in the world, as it puts restrictions on small farmers.

In November 2015, Indonesian government together with Malaysia set up a new body called the Council of Palm Oil Producing Countries. Both countries account for 85% of world’s palm oil production. The new body aims to establish a new standard for sustainable palm oil.

Since 2009, Indonesia already has its own certification standard, named as Indonesia Sustainable Palm Oil (ISPO). ISPO is compulsory on paper, to the extent that those without ISPO cannot export their products. However, until February 2016, according to Antara, only 142 ISPO certificates have been awarded to oil palm plantation companies.