Indonesian women: Their choices, ‘destiny’

Change Size

(-/-)

(-/-)

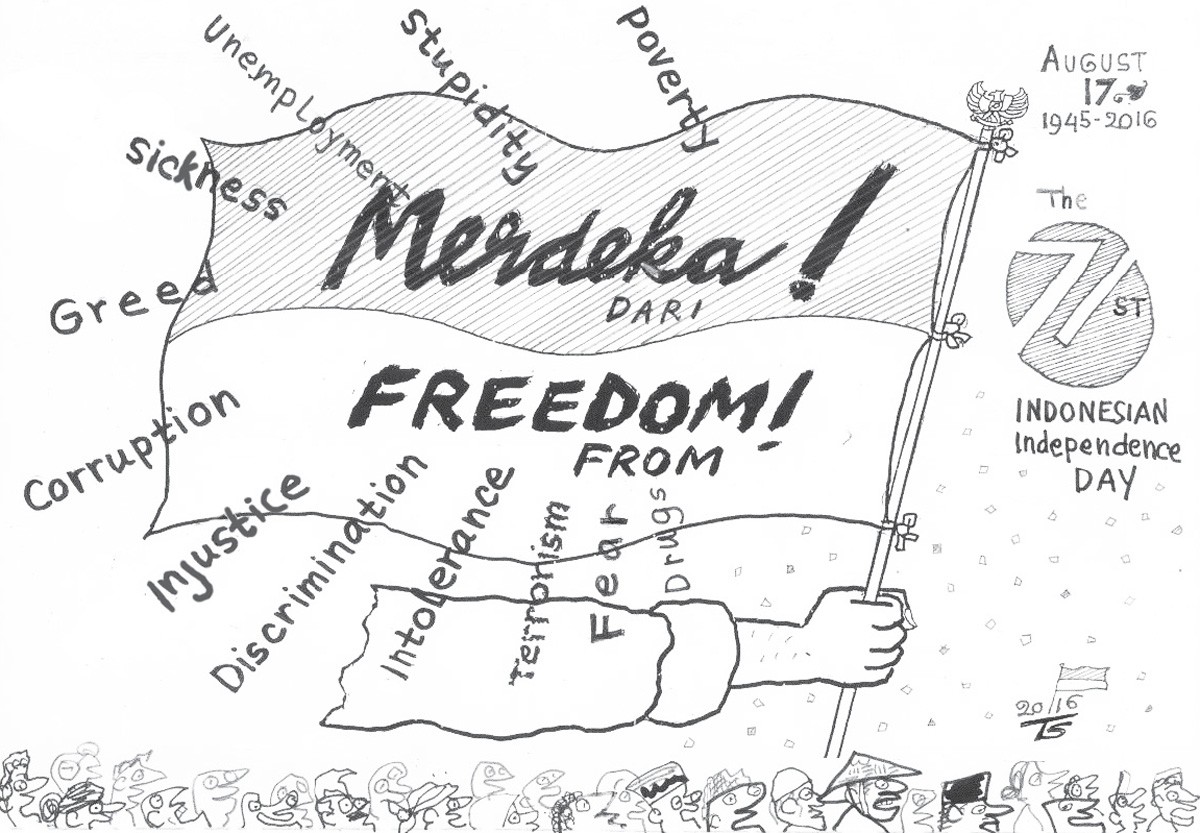

Indonesia has now been independent for 71 years. What has been achieved, especially for women?

The first thing to note is that there is no discrimination against women in the 1945 Constitution, which refers to “all the people of Indonesia”.

Since the first elections in 1955, women have had the right to vote. Nobody questioned that. No surprise then that women have played roles on the battlefield and in politics, and also in education, although there is still great inequality.

Besides a female president, Megawati Soekarnoputri (2001-2004), several Cabinet ministers, a governor, regents and mayors have been women.

However, many women who grew up during the 32 years of the New Order have suffered from new conservative pressures. These are the “Golkar children”, products of the period when Soeharto’s Golkar party was everywhere.

My father was a civil servant and thus my mother was active in the Dharma Wanita women’s organization of the bureaucracy, which was mandatory for civil servants’ wives.

Her position in the organization followed her husband’s position at work. These wives were also active in the Family Welfare Movement (PKK). The PKK was active from the capital right down to the neighborhood level.

The PKK teams, comprising community leaders’ and officials’ wives, organized various activities e.g nutrition counseling for families, services for mothers, babies and children and so on. All these activities defined women as creatures of the domestic realm.

School was another place where we were indoctrinated with conservative ideas. We were taught how women, through PKK and Dharma Wanita, were pillars of the state and pioneers for the motherland.

Even our greatest progressive female thinker Kartini, who was way ahead of her time at the turn of

the century, was turned into a symbol of such conservatism, a figure demure in her traditional dress, depicted as the ideal feminine daughter.

At the time there was another ugly depiction of a certain kind of woman. This story was told through what was said about Gerwani (Indonesian Women’s Movement). We were taught that Gerwani was an organization of evil women, associated with the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), who were of low morals and who tortured captive military heroes by cutting their genitals. So politically active women, as distinct from domestically serving women, were bad.

However they never gave us Gerwani material to read for ourselves or allowed us to meet a Gerwani woman. This scary picture of Gerwani and these women meant that just hearing the word Gerwani silenced us.

Despite more women moving into politics and higher education, the New Order experience continued to define women as essentially creatures of the domestic space. So not once did I hear at school or anywhere about the individual woman and her rights. The word rights (hak) was not in the lexicon of the woman who was to be the servant of the family and the state.

When Soeharto fell in 1998, with great political turmoil fuelled by, among other things, student and peoples’ demonstrations, including women through groups like Suara Ibu Peduli (Voice of Concerned Mothers), the situation changed.

One product of this activist ferment gave birth to the movement for a 30 percent quota of women in political parties and the parliament. There was only minimal opposition from the patriarchy as women’s votes were important. Another product of the reformasi period was the establishment of the National Commission on Violence Against Women.

In the public sphere, Indonesian women have made many positive achievements. But let’s look at the everyday problems still encountered by many.

If you are a woman under the age of 30, you will often encounter the question, “Are you married yet?” To not be married is still seen as something strange and unnatural: an avoidance of a woman’s natural destiny.

This continues even as there are more women who don’t marry, or decide not to have children, especially in big cities like Jakarta.

This aggressive assertion that a woman has a natural destiny to which she must conform to not only impacts the unmarried woman, but also those who have married.

How many times will somebody, another woman usually, suddenly start caressing one’s tummy: “Something inside, yes?” A married woman whose tummy is not a “six-pack” can often incur this invasion of physical territory.

Relating to each other as one womb to another, rather than as one human to another, is assumed to be something natural among many women.

All these behaviors are imposed from childhood, with women themselves having no say in accepting them or not. Women are still defined as the wife or the mother; someone who is aware of the limits imposed upon her by her alleged natural destiny.

Friends who have chosen to remain single or have no children are often motivated by their commitment to work, their profession or other endeavors. They are often the backbone of families and often sustain even the extended family.

They realize how difficult it is to materially support a family and meet the needs of children in today’s world, especially when living in big cities. So, consciously, they choose to have just one child or not to have children at all.

We see it too in a broader context, how thousands of women are “permitted” to fly to distant lands to work. They leave their children and their husband and his extended family to earn a living for their family. Family, village, country; all gladly accept the contributions from the labor of these women without ever questioning how the state works. And still, it is the man/husband who is positioned as the family head who determines the “policy” of family life.

And so, the first question to a woman should not just be: Sudah kawin belum? (Are you married yet?) but “Where are you working?” or “What are you doing these days?” as would be asked of a man.

As long as women are seen as having a narrowly defined kodrat or natural destiny, they will not be able to enjoy fundamental freedoms. Only when women are fully seen as equal human beings, defined only by what they are able to do and achieve, will they have real rights: freedom to work, freedom from violence and sexual harassment and freedom from a sexist culture.

Only then will our Constitution have real meaning.

_____________________________________

The writer is a playwright, a director and a theater producer and co-founder of Institut Ungu (Purple Institute, Women’s Art and Cultural Space ).