Jokowi as UNWOMEN ambassador: Don't forget state violence

Another largely ignored issue is state violence, in which the state disproportionately targets, polices and offers no protection for certain groups of women due to their ‘immorality’ or certain backgrounds. Hence, the state, either by actively perpetuating its stance or by being silent, has normalized and nurtured fertile grounds for violence.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

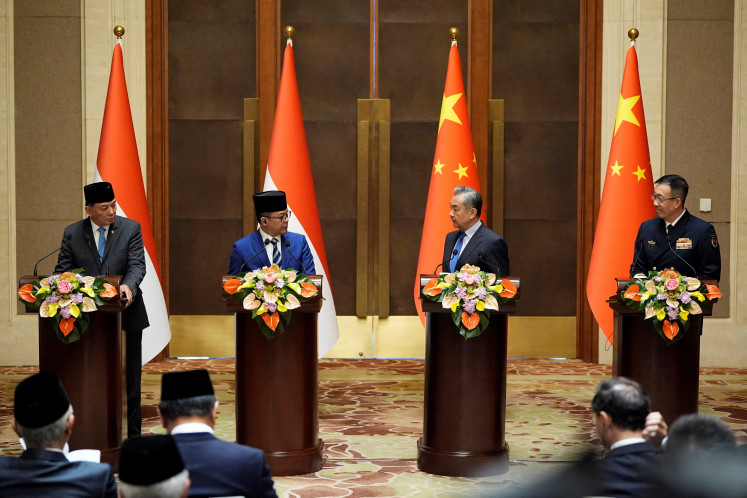

Fight for rights: Transsexuals stage a peaceful rally in Jakarta to urge the state to do more to protect the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people. The Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) called for legislation to ban lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) activities in Indonesia. (Kompas.com/-)

Fight for rights: Transsexuals stage a peaceful rally in Jakarta to urge the state to do more to protect the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people. The Indonesian Ulema Council (MUI) called for legislation to ban lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) activities in Indonesia. (Kompas.com/-)

I

n early September 2016, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo was selected as one of the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women (UNWOMEN)’s HeForShe ambassadors in the “Impact 10x10x10” program that engages world leaders, corporations and universities to mainstream gender justice. Along with other country leaders—including US President Barack Obama and Japan Prime Minister Shinzo Abe, Jokowi has committed to championing gender equality, and came up with specific actions to ensure equal opportunities for women, readily launching a nationwide campaign on women’s rights.

Jokowi has committed to three major particular actions to improve women’s lives, including aims to reach at least a 30 percent representation of women in the House of Representatives, reducing maternal mortality and improving access to reproductive health services, as well as ending violence against women and girls. While it is necessary to address these issues, what can be problematic in his programs is the underlying assumptions that women are monolithic and share similar experiences and vulnerabilities. In fact, particular groups of women are even more prone to violence.

Another largely ignored issue is state violence, in which the state disproportionately targets, polices and offers no protection for certain groups of women due to their ‘immorality’ or certain backgrounds. Hence, the state, either by actively perpetuating its stance or by being silent, has normalized and nurtured fertile grounds for violence.

UN Women Goodwill Ambassador Emma Watson in her speech highlighted the importance of male involvement in addressing gender inequality. Without undermining its values and importance, the overemphasis on male involvement reveals that rights have been individualized. In other words, the responsibilities to address inequality have been transferred to individuals, ignoring the fact it is the state that oftentimes plays pivotal roles in perpetuating stigma and discrimination through its policies and practices that impede certain groups of women to be able to access their basic rights, or even deliberately inflict violent acts on women for political purposes.

Indonesia has not yet come to terms with its dark past of the 1965 violence and the May 1998 tragedy. In his attempt to banish communism from Indonesia, Soeharto’s New Order regime perpetuated myths that women activists of Gerakan Wanita Indonesia - Gerwani (Indonesian Women Movement) allegedly affiliated with communism and tortured and massacred a number of Indonesian military generals, while dancing naked and performing non-normative or ‘lesbian’ sexual practices in front of them. Gerwani’s so-called ‘sexual evilness’ was imbricated with the murderous acts and hence immorality after the 1965 Soeharto regime found its justifications to murder, send to camps and imprison Gerwani members without trial for years. In the camps, these women also experienced sexual violence and harassment. Furthermore, the propaganda of lesbian Gerwani members provided a platform for state to police non-normative sexuality and the legitimizing of heterosexual family principles alongside traditional gender norms as the state’s ideology.

In May 1998, before the downfall of authoritarian New Order, hundreds of Chinese-Indonesian women were raped, against the backdrop of mass burnings and looted shops and buildings. This anti-Chinese turmoil was an attempt to blame the ethnic Chinese for the krisis moneter (economic crisis). In Masculinity, Sexuality and Islam (2015), Australian scholar Kathryn Robinson shows that there were recurring patterns of violence against women—including murder and rape—by soldiers and the military in places with organized resistance to the state, including East Timor and Papua. Women were often used as instruments of war.

The collapse of the New Order era opened up spaces for previously suppressed Islamic fundamentalist politics to proliferate and exert their power through ‘moral-based’ regulations that controlled and sanctioned women’s bodies, attire and sexualities. In reality, the legislation of the pornography bill, along with perda syariah (local bylaws) that were believed to be able to reduce social ills, instead resulted in more violence against women. The province of Aceh, granted autonomy to be a special province implementing sharia law, is reported to have high numbers of sexual harassment and domestic violence. In this case, the silence of the state, or even the state’s nods to support Islamic fundamentalist politics, has nurtured it to burgeon and expand its power, while putting women and other minority groups in more vulnerable positions.

During the current anti-LGBT meltdown in the country, state officials have also been actively involved in condemning and giving homophobic public statements that has increasingly fueled hostility toward lesbians and waria (transgender women). Women also have different sexual orientations and lesbians are also a part of ‘women.’ Although the National Commission on Anti-Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan) has acknowledged a waria as a ‘social woman’ (perempuan sosial), the state is still absent in providing protection to them. Many warias are harassed and even sent to inhumane assessment camps by local public order officers, alongside street children and homeless people. The state seems to neglect complex issues and exclusions experienced by the waria community. The fact that warias face underlying impediments to access education and employment have led them to work on streets, as street musicians or sex workers.

We often ignore the fact that state and power often come in gendered forms—it is not always neutral. Through positioning women and other minority groups as ‘second class citizens’ and reproducing structural violence, the state has restored its masculine dominance. It exerts masculine power through its silence, even bowing to and normalizing violence and discrimination. Instead of HeForShe, the state does ‘She for He’— it crucifies women and minority groups for the benefit of its own power. Hence, it is necessary to remind everyone that while rights have been increasingly individualized, let us not forget about the roles of the state in perpetuating structural injustice, inequality and control over certain groups that amputate their access to basic rights.

***

The writer, who obtained his Master’s in public policy from the National University of Singapore, is the writer of Coming Out and a lecturer of gender and sexuality studies. He is currently pursuing his Masters by Research in Gender and Cultural Studies in The University of Sydney.

---------------

We are looking for information, opinions, and in-depth analysis from experts or scholars in a variety of fields. We choose articles based on facts or opinions about general news, as well as quality analysis and commentary about Indonesia or international events. Send your piece to community@jakpost.com.