Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsFine dining approach to Indonesian seafood

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

C

hef Ragil Imam Wibowo’s Samudera Nusantara seafood dinner at Nusa Indonesian Gastronomy in Kemang, South Jakarta, is another fine-dining approach to contemporizing the country’s regional dishes.

The bounty of the samudera nusantara (oceans of the Indonesian archipelago) has mostly been tweaked into concoctions conforming to the gastronomic norms of the West, which, however, leave their origin and regionality barely recognizable.

When invited to try Nusa Indonesia Gastronomy’s eight-course Samudera Nusantara seafood dinner, available until Sept. 17, the first bite-sized amuse-bouche to savor, a slice of thin, crusty bread made from sago palm starch topped with trevally meat floss looked like a slice of mini pizza.

This piece, presented atop a glass with decorative black rice inside, turns out to be a modern take on Papua’s sagu sap — baked sago bread of the Marind tribe in Merauke, originally topped with kangaroo or deer meat or pork if the previous two weren’t available, according to chef Ragil Imam Wibowo.

I wouldn’t have known of its Papuan origin if Ragil hadn’t shown me a smartphone video of how “jungle” chef Cato, his mentor while in Papua, used hot stones to communally prepare it with sago palm worms as its topping.

Ragil’s way of turning this communal jungle food into an hors d’oeuvre is so disconnected from the original that the Merauke hunter-gatherers wouldn’t be able to identify it and yet so urbanely familiar that big shopping-mall frequenters would easily recognize it as that popular open pie of Italian origin.

With the former being deprived of its identity in order to make it relevant to cosmopolitan palates, it is hard not to think that the whole fine-dining enterprise could end up blurring regional identity and distinctiveness by way of assimilation and absorption.

Of course, this pursuit could also be seen as promoting the rebirth of lowly regional dishes into the realm of the sophisticated, as in Ragil’s soupy interpretation of ikan arsik, the signature spicy fish dish of the Toba Batak and Mandailing peoples of North Sumatra.

Here, defining notes of andaliman (Indonesian Sichuan pepper) whose hotness and spiciness have been judiciously toned down and rias (torch ginger) were key to the original dish’s flavors.

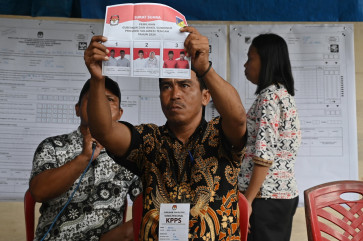

Ready to serve: Soft shell crab, batter covered and deep fried, is soaked in a sea of andaliman curry. (JP/Arif Suryobuwono)Another refinement lay in the replacement of the usual, bony common carp by fabulous tasting gindara (escolar) fish of around 40 grams, far below the 170 gr keriorrhea-inducing threshold. It came from the waters off Kendari, the freshest source of the buttery and succulent oily fish, according to the waiter who served it to me.

When the main course arrived — mahi-mahi with mild-tasting, savory tempoyak (fermented durian) sauce decorated with surprisingly sweet-tasting blue pea flowers and two bird’s eye chilis — the seemingly knowledgeable waiter wasn’t able to tell me why the fish had to come from Balinese rather than Kendari waters.

Then, he left me without any cutlery. If I hadn’t been in a fine-dining restaurant, I wouldn’t have minded eating with my hands, especially given the specialty rice served to go with the dish: firmer and less sticky Solok white rice and a blend of geographical indication-registered, tastier, softer and stickier Adan Krayan black and white rice. This serving of a basket of rice, however, helped fill me up.

New twist: Balinese fresh seaweed salad is sprinkled with tiny mango cubes dressed with fish brine stock. (JP/Arif Suryobuwono)The lovely chocolate dessert served right afterward consisted of Bali’s Tabanan chocolate mousse glazed with Flores’ Tana Zozo chocolate, andaliman gelato made from Banyuwangi’s Glenmore chocolate and very sweet dollops made from Aceh’s Pidie Jaya chocolate. Now that they have been made into dessert, it is pointless to boast their regional identity.

The drinks paired with each course were coconut water-based rose apple, pineapple, torch ginger and sugar-cane juices in different fermentation stages. Wine was preferable yet there was none.

“No one could tell me with absolute certainty whether wine destroys Indonesian food or vice versa,” said Ragil, adding that he quit drinking after becoming diabetic.

Fish treat: Tamarillo and passion fruit sorbet is served before dessert to cleanse the palate. (JP/Arif Suryobuwono)But for now, let’s focus on great-tasting, easily recognizable dishes that defy alienation, perhaps because it’s best to have them as is, with some enhancements: the last, the third and second amuse-bouches, bulung buni(Balinese fresh seaweed salad) with a kuah pindang (Balinese fruit salad) fish broth dressing, fresh oyster with lemon basil and pink espuma made from red dragon fruit, shallot and dabu-dabu (tomato relish), and bakwan cumi (squid fritters) respectively; the deep-fried, batter-covered soft shell crab in candlenut-flavored curry soup that was served before the main course, and the gohu (Indonesian ceviche) appetizer, tiger prawn was used instead of the usual yellowfin tuna.

Except for the oyster, which is commonly eaten fresh everywhere, the other dishes clearly retained their regional identity.

So, haute cuisine’s penchant for undoing the ordinary by obscuring the identity of common, ethnic, tribal cuisines it absorbs rather than highlighting their intrinsic charms has not been entirely addressed but it was full of effort.

Tasty: An oyster from the Java Sea topped with dabu-dabu espuma is served during the eight-course Samudera Nusantara seafood dinner at Nusa Indonesian Gastronomy in Kemang, South Jakarta. (JP/Arif Suryobuwono)