Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsLessons from three disasters

Analysts-on-the-quick are already comparing the recent disasters

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

nalysts-on-the-quick are already comparing the recent disasters. “Chile was ready for the quake, Haiti wasn’t,” writes Frank Bajak of the Associated Press. Although the Chile earthquake was 500 times stronger than Haiti’s, with hundreds of immediate aftershocks, Chile is getting the relief effort well under way, long before the donor community can step in with yet another humanitarian response.

What made Chile an almost earthquake-proof nation? Did Chile just get lucky?

“Strong building codes, robust emergency response and a long history of handling seismic catastrophes,” argues Bajak. Plus loads of human capital. “On a per capita basis,” Bajak quotes Brian Tucker of GeoHazard says in the same article, “Chile has more world-renowned seismologists and earthquake engineers than anywhere else.”

But more than building codes and an abundance of expertise is the quality of a country’s governance to respond to disasters. Not just government response, but an entire collective effort that includes the business community, the media, and organized citizenry.

Imagine, however, a scenario of hope for Haiti, one that might look like this.

2015 in Port-au-Prince. A major conference is about to begin, celebrating Haiti’s progress since the earthquake of 2010. Alphonse Michel, Minister of Public Works, Transport, and Communications is talking to Bonaventure Ouvert, a Haitian journalist.

“After the earthquake of 2010, more than our buildings had collapsed,” says Michel. “Our economy was in ruins. There was almost no civil service. Our morale was devastated. Everyone assumed that Haiti would just drop deeper into our historic pattern of corruption and instability.”

“Our government has learned how to work through partnerships. In reconstruction, and in activities ranging from social services to free zones to agriculture, we use a variety of public-private-nonprofit partnerships, all of them ethically led and fully accountable.”

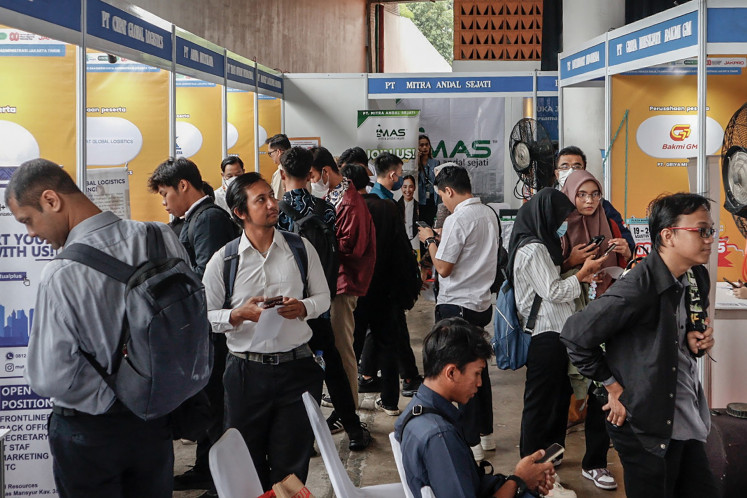

At the same time, across the globe in Indonesia, Minister Ismaili Hadad of Trade and Investment talks to Maria Suntoro, bureau chief of the CNN in Southeast Asia.

“The December 2004 tsunami destroyed nearly everything in Banda Aceh, but we resurrected its economy. We entered into a peace pact with the rebels, gave them concessions, converted them into stakeholders. Eleven years after the tsunami, the donors involved in reconstruction have left the province with a lasting imprint of peace and prosperity.”

Wouldn’t it be wonderful if the two largest civilian disasters in modern history ended so well? What will it take?

In Haiti, some important ingredients are already in place. The country has an excellent economic strategy, developed last year with the help of Oxford economist Paul Collier. It has worldwide support including Bill and Hillary Clinton. Haiti has preferred access to US markets.

What Haiti lacks, however, is a realistic strategy to control corruption. Accusations of corruption fly freely — and indeed Haiti is rated as one of the most corrupt countries in the world.

The good news is that around the world, there are many anti-corruption success stories. Fry “big fish.” Mobilize citizens and business groups to make government more transparent. Use the same tricks in fighting organized crime.

Indonesia provides relevant lessons. In October 2004, fresh from his victory at the polls, President Bambang Susilo Yudhoyono immediately tackled the Aceh separatist problem. When the December 2004 tsunami struck Aceh, it killed over 200,000 people and left millions more homeless.

President Yudhoyono and his chief negotiator, Jusuf Kalla, wasted no time. They set in motion a peace process. They gave concessions, among them, a distribution of revenues from natural resources. They allowed the rebels full participation in the political process.

Drawing the rebels into the electoral process was a masterstroke. The rebel movement was de-fanged. Hence the groundwork for peace was firmly established.

At the same time, President Yudhoyono gave the national fight against corruption high priority. He empowered the anticorruption agency to go after high-level perpetrators of corruption from all parties and all sectors.

Six years after the tsunami, Aceh is at peace, the province rebuilt.

Haiti is a tiny country compared with Indonesia, and there is no secessionist movement. But Haitian politics is fractious and unstable. “It’s what I’d call a perfect storm for high corruption risk,” says Roslyn Hees, author of Preventing Corruption in Humanitarian Operations.

“I want this to be a new country,” President René Préval declared. “I want it to be totally different.”

How might he lead Haiti in the direction of good governance?

First, convene leaders from government, business, and civil society to develop a strategy for governance. Together they would work through a formula: Corruption equals Monopoly plus Discretion minus Accountability. To control corruption, monopoly must be reduced, competition expanded, official discretion limited if not altogether eliminated. A cost-benefit analysis of various anticorruption initiatives would complete the exercise.

And finally, the Haitian leaders would consider the politics of reform. In the next six to twelve months, leaders must build momentum and popular support. Citizens and business people must tell the government what’s working and what’s not.

The international community can help. In the reconstruction, donors should work through real partnerships rather than through permanent enclaves or receivership arrangements. Once again, the experience of Indonesia might provide inspiration.

In Aceh, the global donor community created what Dr. Marcus Mietzner of Australian National University called a “Woodstock effect”, a kind of development aid love fest that brought together a multitude of donors of all hues, sizes and shapes. From the European Union to the Scientology Church, the province received a huge influx of money and aid workers.

But development and humanitarian assistance went beyond reconstruction. The European Union, for example, linked the reconstruction effort to the peace process. No peace, no money.

Then, the creation of the Badan Rehabilatasi dan Rekonstruksi (BRR) managed donor assistance. It was an all-inclusive Aceh-based agency composed of provincial and central government agencies and civil society groups. In 2005, at the peak of the reconstruction effort, the BRR managed development assistance from 55 countries including 900 NGOs, 800 national and international organizations, and 8000 foreign workers and volunteers.

Haiti might go further. Donors might want to consider supporting a Haiti Leadership Academy. It would build on Haiti’s vision of governance featuring public-private partnerships, bottom-up participation, and accountability. It would meet urgent short-term needs for skills in reconstruction and in managing free zones. But its long-term goal would be to educate the next generation of Haiti’s leaders.

Let us hope that, like Aceh, Haiti will testify that great disasters can lead to great reforms. From underneath the immense rubble of human tragedy lies the potential for a collective resurgence.

Robert Klitgaard is the author of a new report Addressing Corruption in Haiti www.cgu.edu/pages/6259.asp. A University professor at Claremont Graduate University and former professor at Harvard Kennedy School of Government, he has been an adviser and researcher in 30 countries, including Haiti during president Aristide’s first term. Tess Cruz-del Rosario is a senior research fellow at the Centre on Asia and Globalisation at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy