Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsMaking nature work

Fueled: Suryasi shows off her biogas stove in her kitchen in Senduro, Lumajang, East Java

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

F

span class="caption" style="width: 398px;">Fueled: Suryasi shows off her biogas stove in her kitchen in Senduro, Lumajang, East Java. Courtesy of UNDP“Smell this,” the man urged, holding up a plastic jug filled with a thick brown liquid. Knowing the substance was produced from cow excrement, no one looked eager to take a whiff.

After more prodding, those present gave in. The smell was, surprisingly, not fecal, but rather sweet from fermentation, like some sort of sordid homebrewed beer.

And in a similar vein of entrepreneurship as those who distill their own spirits, Esti Raharjo created that redolent substance — actually a fertilizer — as part of a larger plan that revolves around cow feces in Senduro, a subdistrict of Lumajang, East Java.

Traveling to the area from Lumajang’s town center, one passes flourishing rice fields and teak plantations, as well as signs welcoming visitors to both a “kampung pisang” (banana kampong) and a “kawasan agropolitan” (agropolitan region).

Continuing up the hill with Mount Semeru looming in the vicinity, one eventually arrives at the site where Esti’s scheme was started two years ago.

Several dozen houses line the steep road; behind one stood seven doe-eyed cows in a neat row.

But, these cows’ abode is different. After one defecated onto the concrete at its feet, their owner, Pak Torima, used a broom to shovel the waste into a channel built in the concrete. That channel led to a hole, with Pak Torima assisting the refuse there with bucketfuls of water.

What happens next cannot actually be observed, but the result can be seen several meters away in Pak Torima’s kitchen. He lit his stove with a lighter and blue flames licked upward. Biogas.

Pak Torima’s household shares the biogas unit with a neighbor who also keeps milk cows. The neighbor, Haji Lido, describes the money they saved from not having to pay for LPG (liquefied petroleum gas) canisters or wood for cooking. “We can give our kids money to buy sweets now,” he says.

Pak Torima discusses the time and labor he is spared. “It had become difficult to find wood. Now I don’t have to go around looking for wood anymore … All the wood is gone around here.”

Yet the process does not end after methane gas is generated in underground domes — there are currently 15 in Lumajang — and channeled into kitchens to fuel stoves and lamps. Waste still remains, and it is taken, dried and either sold as fertilizer or brought about a dozen kilometers away to a factory.

Visitors will immediately be struck by the powerful odor emanating from the site that rumbles with the sound of various machines at work. One man stands over a stove stirring what he said was fish oil — thick and greasy — to be added to the biogas waste.

Another takes a sack of white powder that prevents spoilage and pours it in a giant vessel. And yet another manages a machine that was spitting out small brown pellets to be dried in the sun.

They are manufacturing fish feed, which will later be tossed into ponds filled with nila and gurami set picturesquely against rippling streams. One of those pond’s caretakers, Abdul Wahid, says he purchases the feed for Rp 15,000 (US$1.60) per kilogram, whereas before he had to buy more expensive feed at the store.

“It is cheaper and the quality is the same,” Abdul’s partner, Elfi, says. Pressed about the quality, Elfi adds, “We can see from observing the fish and how they develop that the food is good.”

Esti describes what he has established as “an integrated biogas model”, and after seeing what happens in Senduro’s cow sheds and kitchens, at the feed factory and among the fish ponds used by hobby fisherman who pay Abdul and Elfi Rp 15,000 for each kilogram of fish they catch, he certainly seems to be on to something.

The biogas project Esti is managing in Lumajang is supported by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and is described as a “pro-poor biogas model”.

UNDP spokesperson Tomi Soetjipto says, “It’s one thing to help out the poor and the disadvantaged, but it’s another thing to ensure they can stand on their own feet. Being pro-poor means we want to make sure that our assistance is putting people — in this case the villagers in Lumajang — at the center of human development. The biogas project must be designed to put the villagers not only as beneficiaries but also

as drivers.”

These biogas setups are not cheap, each unit costing approximately Rp 10 million, with the UNDP utilizing a microcredit scheme for payment. UNDP biogas project manager Verania Andria says, “It is very common that intervention providing biogas stops at the access to energy issue, but is not designed to add economic value along its supply chain. The UNDP is piloting this by using an energy-environment-economy approach.”

Aside from the financial assistance biogas provides to small-scale farmers on multiple levels — from the gas to fuel their stoves to the money received from selling the remaining waste — there is no denying the environmental benefits from the decline in wood scavenging and the dumping of cow feces in the river (as the practice had been before).

An additional use for the biogas waste can be observed at an experimental site. That sweet-smelling brown liquid Esti wanted people to smell — and that contains a secret ingredient he refused to disclose — is being used to fertilize a rice field lining the road to Senduro. Young, deep green shoots cover the area, while only a few dozen meters away sits a Pertamina station, a reminder while observing this model energy effort of the dependence on fuel and the recent and raucous demonstrations against the government’s plan to raise gasoline prices.

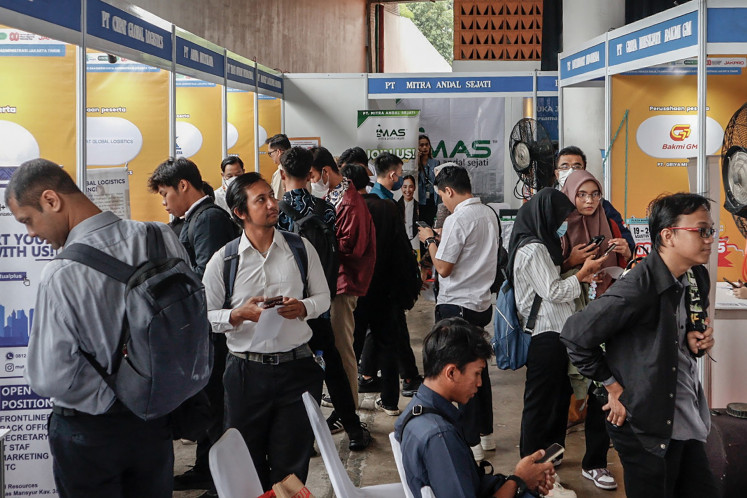

At work: Methane gas produced from the waste from these cows is used to fuel stoves and lamps in equipped homes in Lumajang, East Java.At an event with Lumajang’s regent, H. Sjahrazad Masdar, to mark Senduro’s biogas efforts, Sjahrazad and others made speeches about caring for the environment and supporting organic farming in the area while flanked by bunches of bananas, giant avocados and piles of snakefruit, all grown locally. Steaming plates of different varieties of sweet potatoes were later offered to attendees, the result the impression of a land of true — and organic — plenty.

Meters away, Suryasi and her sister Suryami showed off their own UNDP biogas system to crowds of onlookers, their cows grumbling at the disruption. Later, the school’s marching band performed, with Suryasi’s daughter one of the majorettes spinning and twirling a baton.

And the spinning of the energy-environment-economy circle continues as well with this project that begins with those demure cows and moves to man and then to roaring machine and then back to nature.

Haji Lido spoke of his plans for the future, to start a home industry making and selling kerupuk now that he has a practically unlimited amount of gas at his disposal. As Suryasi, who lives across the street, snaps photos of her daughter performing in the parade, what is clear is that the future remains open, with man, nature and machine — as well as energy, the environment and the economy — continuing their circle of interdependence.