'Ojung': Rattan wars for rain

Get set: Clothed in black, a babuto (referee) takes his stance, marking the beginning of a rattan stick fight during the ojung ritual

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Get set: Clothed in black, a babuto (referee) takes his stance, marking the beginning of a rattan stick fight during the ojung ritual.

Braving the heat of the sun, residents of a village in Malang regency, East Java, gathered around a wide open stage after noon prayers recently to watch traditional rattan stick fighting, a local ritual called ojung.

In the ritual, two fighters engage in a combat fought by means of rattan sticks believed to have magical powers, the fight ending when one is wounded. Also known as rattan war, ojung symbolizes devotion and sacrifice rendered to God as a plea for rain during a long drought.

This tradition, handed down to descendants of people from Madura who left the island and settled in various regions, is preserved in Sempring village, which has a majority Madurese population, located in Pagelaran district, Malang regency, 30 kilometers south of Malang town square.

Ojung was recently conducted by the people of Sempring after an eight-month dry season that has parched local wells and farm land. At 1 p.m. on the dot, gamelan instruments and an organ were played to accompany traditional songs and mark the start of the ritual.

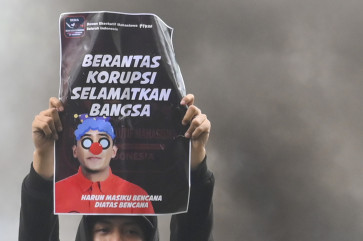

A religious figure opened the event with a sermon and prayer, followed by the committee's announcement to allow ojung participants to mount the stage, where referees called babuto were ready. Clad in black, the referees are village elders or community leader, masters in martial arts and guardians of village security.

Fighters took off their shirts, wrapping sarongs around their waists and donning caps. Each picked up a rattan stick already prepared by the committee; the sticks are so pliant they can be easily bent.

The music continued, building tension among combatants and spectators alike. Based on the traditional rules, each fighter is allowed three chances to strike his opponent, who must parry the blows. The face, chest and legs are forbidden targets, leaving only the waist and back.

Ojung knows no duration; the length of each bout is at the discretion of the referee in charge and his attendants, who closely observe the fighters' conditions. 'The match is ended if the fighters appear to be getting too worked up; this prevents the creation of a vengeful atmosphere in the ritual,' said Sukirno, 64, a babuto.

Two participants were set to fight, facing each other, with a referee between them, dancing. Each of the fighters was free to strike with his rattan stick first, according to their consensus, and both were also free to dance to the musical rhythms. When a blow missed its target, the lucky fighter would dance with exhilaration.

It was already late afternoon, but many more young fighters were waiting for their turn to participate in ojung, which this time had adult, youth and child participants. Galih, 23, a stick fighter, said 'I was burning from the rattan floggings ' I had no preparation for the match. I don't know my opponent, but we'll be acquainted when the ritual is over.'

Taking pride in their bravery at joining this time-honored ritual, the fighters embraced at the close of ojung. Their bouts also constitute a form of dedication and sacrifice to the village community, as the blood shed from their wounds is expected to speedily bring about rain.

The tradition will continue to be practiced by local villagers, for as long as values of communal sacrifice and social harmony remain alive.

' Photos by Aman Rochman