How to make Chinese-Indonesian railway cooperation work

In Indonesia, months of debate and a media circus have stalled the construction of a 145-kilometer Jakarta-Bandung railway, with various policymakers, business stakeholders and representatives from NGOs trading jabs in newswires over the project’s feasibility. It was not an appetizing sight for a project that was initially devised as the paragon of China’s infrastructure expansion in Asia. Earlier this year, I reflected on our domestic political brouhaha with irony inside a high-speed train from the capital Beijing to Harbin, a major city in northeast China.

Change Size

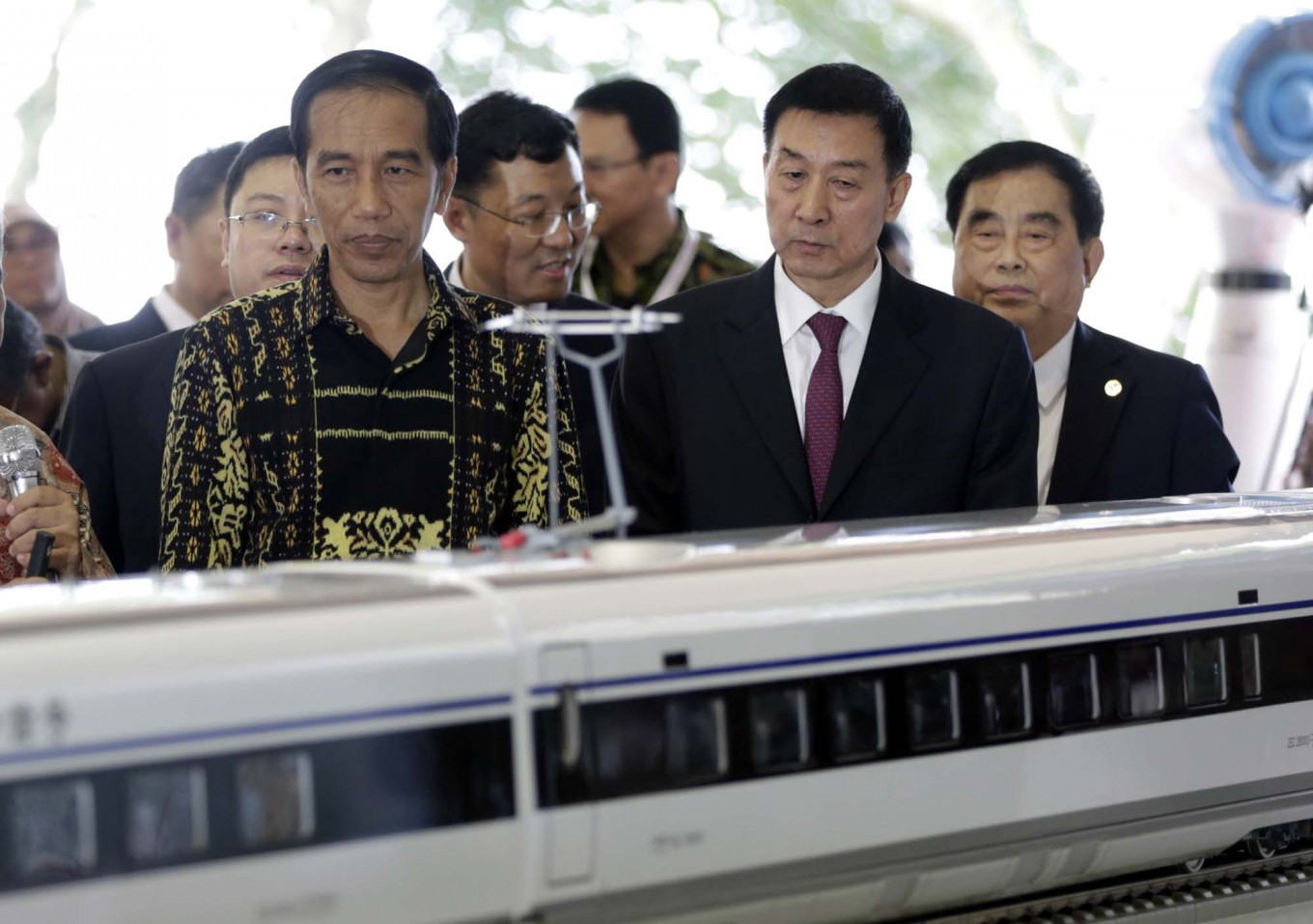

Indonesian president Joko Widodo, left, inspects a model of the high-speed train which will connect the capital city of Jakarta to the country's fourth largest city, Bandung, with President of China Railway Corp. Sheng Guangzu, right, Chinese State Councillor Wang Yong, second right, and Chinese Ambassador to Indonesia Xie Feng, third right, during the groundbreaking ceremony for the construction of its railway in Cikalong Wetan, West Java, Indonesia, Thursday, Jan. 21, 2016. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

Indonesian president Joko Widodo, left, inspects a model of the high-speed train which will connect the capital city of Jakarta to the country's fourth largest city, Bandung, with President of China Railway Corp. Sheng Guangzu, right, Chinese State Councillor Wang Yong, second right, and Chinese Ambassador to Indonesia Xie Feng, third right, during the groundbreaking ceremony for the construction of its railway in Cikalong Wetan, West Java, Indonesia, Thursday, Jan. 21, 2016. (AP Photo/Dita Alangkara)

I

n infrastructure development, the enigma about China is that it has both the most efficient system in the world and the least understood one.

In Indonesia, months of debate and a media circus have stalled the construction of a 145-kilometer Jakarta-Bandung railway, with various policymakers, business stakeholders and representatives from NGOs trading jabs in newswires over the project’s feasibility.

It was not an appetizing sight for a project that was initially devised as the paragon of China’s infrastructure expansion in Asia. Earlier this year, I reflected on our domestic political brouhaha with irony inside a high-speed train from the capital Beijing to Harbin, a major city in northeast China.

The Beijing-Harbin railway spans 1,250 kilometers, a distance that is equivalent to going from Jakarta to Bali, and I felt somewhat chagrined that Indonesia found it so difficult to construct a railway that would only be a 10th of its distance.

My Chinese professor had an explanation why infrastructure development in his country could be so ruthlessly effective: “In democratic countries you face more constraints, but here in China you face rule of man, not rule of law.”

The multi-billion-dollar question now is whether the economic cooperation between Indonesia and China, which are two countries with strikingly different political systems, can prosper.

If the economic cost was the only concern, the Indonesian government’s decision to grant China, not Japan, the responsibility of building the Jakarta-Bandung bullet train project is justifiable.

A study from the World Bank office in Beijing shows that the construction of China’s high-speed railway — defined as those that can be traveled by trains with maximum speeds of 350 kilometers per hour — has a typical infrastructure unit cost of about US$17 million to $21 million per kilometer, excluding land, rolling stock and interest during construction.

In European countries such as France and Spain, similar infrastructure is estimated by the World Bank to cost $25 million to $39 million for every kilometer, while in California, the US, the price tag stands at $51 million.

The efficiency was driven by the fact that, over the past decade, China has built more high-speed railway infrastructure than any other country, with the mainland now boasting a network of more than 12,000 kilometers of high-speed railway routes — the longest in the world.

The notion prevalent among Indonesians that “Made-in-China” products come in cheap prices but questionable quality is purely a misconception.

In reality, China currently possesses the technical know-how for building railway networks in the fastest and cheapest way possible, thanks to their highly standardized railway infrastructure design and a successful localization of manufacturing of its goods and components.

The predicament faced by Chinese firms, however, is that building a railway network on their own turf and in Indonesia might be totally different ball games.

To start, Chinese and Indonesian state-owned enterprises (SOEs) have stark differences in perspectives and working culture, which means the cooperation between the two camps is unlikely to be smooth.

Unlike in China, where SOEs basically act as the government’s developmental tools in a highly centralized economy, Indonesian SOEs are not backed by political support that is as strong as that of their Chinese counterparts. They instead possess a relatively high degree of independence.

In addition, Chinese firms were accustomed to the authoritarian-style infrastructure-building approach, the imposition of which sometimes comes at the cost of environmental degradation and violations of human rights, with reports showing that many Chinese citizens were forcefully evicted from their homes or lands without receiving sufficient compensation.

If China wants to be successful in its push to strengthen its regional influence and to eventually emerge as the next global superpower on par with the US, it needs to learn better about democracy, particularly how to do business in countries with strict environmental, governance and transparency standards.

So far, their track record on that is not good. “Some commodity-rich countries have balked at dealing with Chinese firms, troubled by their weak record of social responsibility, which has forced Beijing to explore new ways of doing business,” Elizabeth C. Economy, a noted author who specializes in China’s foreign policy, once wrote.

Nevertheless, the burden does not lie in Beijing alone. For the central government in Jakarta, the political ruckus surrounding the China-backed railway project has sent the wrong signal to foreign investors, exposing the inefficiency of our bureaucracy and the messiness in the decision-making process for infrastructure development under President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo.

For Indonesia to attract more Chinese investors and capitalize on the mainland’s outward investment push, the government could improve itself on three fronts.

First, the government needs to set the investment guidelines very clearly for Chinese investors who — unlike their Japanese or American counterparts — have little business history in Indonesia, while at the same time further cutting bureaucratic hurdles for them.

Second, local Indonesian leaders — from governors and regents to mayors — should be instructed to undertake more efforts to court the Chinese investors and improve governance on the local level. This is because in their home country, Chinese businesspersons are accustomed to having a strong bond with local leaders, who will always be ready to help them cut through bureaucratic red tape while acting as the “political guardians” of their investments.

Third, Indonesian government officials or other local business stakeholders should really avoid making public any disagreement on China-related projects, as that situation can make existing and future Chinese investors very uncomfortable.

That should be noted because in Indonesia some policymakers have the culture of having “roundtable meetings in newspapers” as they prefer to voice their disgruntlement to journalists to garner public support, instead of solving the issue directly with the persons in charge.

China, a country that has a very limited press freedom, values the culture of secrecy where dissenting opinions among officials or businesspersons in public are considered taboo.

Indonesia could reap the maximum benefits from the Jakarta-Bandung bullet train project. For Indonesian SOEs in particular, this is the moment to absorb Chinese technological expertise for our future infrastructure development — a strategy that was applied by Chinese SOEs in 2004, when China demanded technology transfers from German companies as a prerequisite for the right to develop the mainland’s high-speed railway networks.

The inconvenient truth here is that an authoritarian China and a democratic Indonesia were not a match made in heaven and just like an in-love couple with strikingly different personalities, the two countries have so much to do to make their relationship work.

***

The writer is currently pursuing a Master’s degree in public policy at Peking University, China.

---------------

We are looking for information, opinions, and in-depth analysis from experts or scholars in a variety of fields. We choose articles based on facts or opinions about general news, as well as quality analysis and commentary about Indonesia or international events. Send your piece to community@jakpost.com.