Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBeyond charity: Solidarity and role of state in time of pandemic

Is it true that solidarity will strengthen and that societies will be transformed for the better? Is that also the case in Indonesia?

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

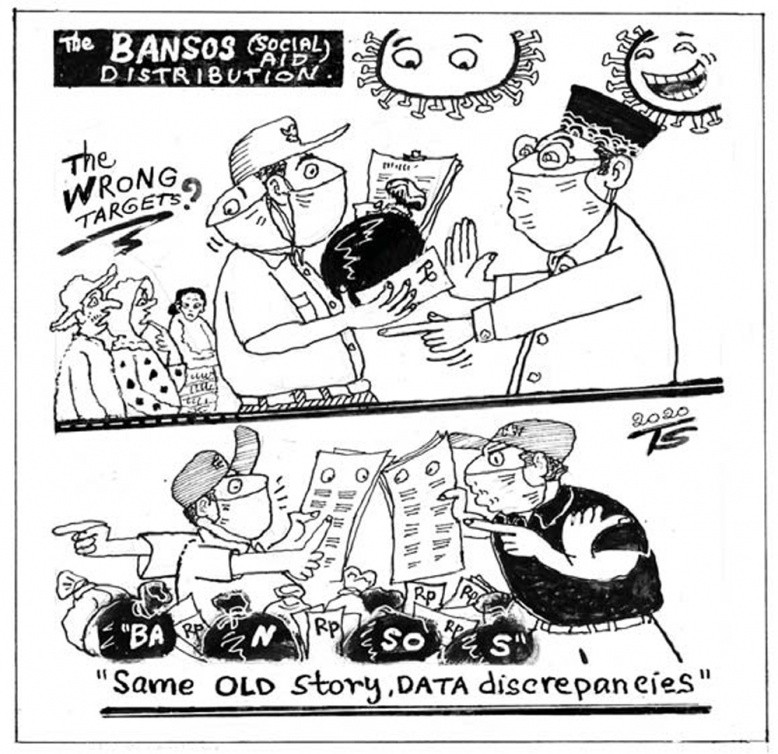

Same old story, data discrepancies. (JP/File)

Same old story, data discrepancies. (JP/File)

A

t this time of the global pandemic, solidarity, many argue, will strengthen and find ways for a better transformation of society. The writer Yuval Noah Harari; also shared this view: In Indonesia, we have also seen flourishing signs of citizens’ solidarity for the needy, indicated by much volunteerism and charity.

Is it true that solidarity will strengthen and that societies will be transformed for the better? Is that also the case in Indonesia? I will reflect on several contexts in Asia and especially Indonesia, following a webinar on the roles of government and society in handling the COVID-19 pandemic in Asia held on April 22 by the Veteran National Development University Jakarta (UPNVJ).

First and foremost, we need to be clear on what we mean by solidarity. It is a concept that has long been discussed academically, mainly as theory, and became particularly relevant amid the mushrooming of studies on social movements.

Solidarity is essentially the feeling of reciprocal sympathy and responsibility among members of a group which promotes mutual support. Such feeling emerges as a reaction to oppression or marginalization against the group or its certain members and works best if they share common goals against “common enemies”.

Solidarity is different from benevolence or charity. Benevolence does not require shared political goals, struggles for the oppressed or the marginalized, or forms of social awareness that aim to change for a better society. Benevolence involves hierarchy, from top to bottom, or from the rich to the poor. It is interpersonal rather than social. Those who join and those who help do not intend to join the struggle or fight together for a common cause but only to help the weak.

In Indonesia, the boundaries between solidarity and benevolence is practically blurred. Several civil society organizations and grassroots communities are raising social assistance to help the groups most affected by the pandemic, such as informal workers, laborers, urban poor and so on. Several individuals, especially public figures, have also flocked to provide food, money, masks, and so on for the poor. One thing in common from all these efforts is that each runs independently without any monitoring or process of evaluation.

In other countries in Asia, solidarity is closely related to the level of public confidence in the government and/or the government’s ability to manage the pandemic. In countries where the government has successfully handled the pandemic, solidarity arises for the global motivation of helping people in other countries. In Taiwan, the rapid response to the pandemic makes people feel safe and protected, including with the government’s strategies and use of technology and information, says Deasy Simandjuntak of Academia Sinica.

In South Korea, effective bureaucracy and well-managed public services has led to an increase in public trust in its leaders for the past few months, as Alvin Qabulsyah observes.

In Singapore, transparent, consistent and data based communication coupled with a multiracial approach have appeared to stabilize people’s confidence and support in their leader, according to Aninda Dewayanti of the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies-Yusof Ishak Singapore.

Japan’s government was initially slow in responding to the pandemic because of its insistence for the Olympics to be held this year. However, with mounting confirmed cases, local governments and civil society urged the government to fight the pandemic more effectively, as noted by Iqra Anugrah of Kyoto University’s Center for Southeast Asian Studies.

In these countries, the needs of citizens are relatively already addressed by the government, so that while domestic solidarity is not very visible, calls for global solidarity strengthened.

Calls and initiatives for solidarity at the domestic level are effectively regulated and managed by their respective governments, such as in Malaysia where local governments provide guidance and regulations for aid distribution, according to M. Riza Nurdin of Universiti Malaya.

In Singapore, the dominance of the government’s role in dealing with a crisis has led to the dependency of citizens on government policy, and only limited advocacy initiatives have been carried out in the community-based informal social sector. Similarly, Musa Maliki in Brunei Darussalam notes how the sultanate dominates all sectors in dealing with the pandemic.

In Indonesia, the level of confidence in the government’s response to the pandemic tends to be low, as a recent survey shows. The formulation of appropriate policies has seen a stuttering beginning; incompetence as well as inconsistency, coupled with communication patterns that are not transparent and tend to be defensive, which have confused people, add to the sense of insecurity.

The government seems more concerned with preserving power, for example by initially dismissing the severity of the pandemic on the grounds of avoiding panicking and tightening control of public expression with narratives of anarchism and arbitrary arrests.

Solidarity is not included in the vocabulary, let alone the government’s strategic policies, because for the administration of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo, the enemy seems to be the citizens themselves who potentially can destabilize the government power. Indications of solidarity within government measures would include, for instance, much more protection of the most vulnerable groups from COVID-19 transmission or promoting national solidarity behind efforts to fight the virus, like what Taiwan's government did.

What we hear every day on television by the spokesperson for the COVID-19 government team is that the number of cases continues to increase because people do not wear masks and still leave the house. The impression is that the government is ignoring widespread expressions among the poor that they have little choice to survive amid limited provision of safety nets.

Global solidarity? It is still far from where we are now. Citizens must deal with the pandemic by relying on themselves. Benevolence or charity can be the initial stage because solidarity has not yet become a shared awareness.

However, as long as solidarity has not been established, relying solely on benevolence can lead to dependency and reaffirm the social class hierarchy between the rich and poor. Benevolence will gradually become a new competition to do good for others.

Solidarity challenges this because solidarity has the capacity to strengthen the resilience of citizens. Solidarity also challenges the practice of bad governance and drives public pressure for accountability.

______

Lecturer, School of Social and Political Sciences, Veteran National Development University Jakarta (UPNVJ), specially appointed associate professor at Osaka University, Japan.