Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsTaking plastics full circle: Creating a sustainable future in Indonesia

Indonesia has an opportunity to take a holistic, cross-stakeholder approach by restoring the nonbiodegradable, fossil fuel-based material to its original aim: to reduce harm to nature.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

hen the first synthetic polymer, celluloid, was invented in 1869, it was envisioned as a more nature-friendly substitute for ivory and tortoiseshell, both sourced from wild animals. Indeed, plastics have become one of mankind’s most ubiquitous and flexible materials, opening up revolutionary possibilities in manufacturing.

However, more than a century and a half on, plastic pollution is now a major environmental challenge. We regularly dispose of large volumes of plastics, which can remain in our environment for centuries: Plastic bottles alone can take up to 450 years to decompose in a landfill.

Sadly, plastics that are not properly disposed of often end up in our oceans, posing a threat to marine environments. In fact, plastic waste makes up 80 percent of all marine pollution, with as much as 10 million tonnes ending up in the world’s oceans each year.

Plastics are undoubtedly a critical part of modern life, but with plastic production expected to double to around 700 million tonnes globally by 2040, managing its use and mitigating its impacts is vital in Indonesia and around the world.

Indonesia’s plastics story

As Southeast Asia’s largest economy, Indonesia is both a major producer and major consumer of plastics.

The United Nations estimates that Indonesia produces 3.2 million tonnes of unmanaged plastic waste, with over a third (1.29 million tonnes) ending up in the ocean. In fact, the country has the unfortunate position of being the world’s fifth-largest contributor to ocean plastic waste.

Indonesia generates more than 7.8 million tonnes of waste annually and according to the World Bank, an estimated 60 percent of this waste is uncollected, disposed of in open dumping sites or leaked from improperly managed landfills.

The country’s recycling rates are stubbornly low, with only an estimated 15 percent of waste currently recycled. Solving the plastics challenge will be crucial for Indonesia to create a more circular and sustainable materials value chain, which could unlock up to US$9.3 billion in annual value.

The good news is that the Indonesian government already has a number of road maps and initiatives in place to tackle its plastic burden, setting ambitious targets to reduce waste at their sources by 30 percent, increase waste handling to 70 percent and eliminate plastic pollution altogether by 2040.

Among these is the National Action Plan on Marine Plastic Debris 2017-2025, which aims to reduce marine plastic debris by 70 percent by 2025. It includes strategies for waste reduction, improved waste management infrastructure and public education campaigns.

Major regions such as Jakarta and Bali have also introduced bans on single-use plastics to reduce needless plastic waste.

Taking a holistic approach, the implementation in 2019 of an extended producer responsibility (EPR) system, known as the Producers’ Waste Reduction Road Map, established a target for producers to reduce the waste generated from products and packaging sales by 30 percent by 2029. The road map is currently at a point where industries and producers must submit a long-term EPR plan.

However, it must be acknowledged there are challenges in embedding enhanced plastics circularity. Recycled plastics are typically more expensive, costing at least 10-20 percent more than virgin plastics, which can hinder adoption. There is also poor awareness on circularity and alternatives to virgin plastics among both manufacturers and consumers, particularly small and medium enterprises (SMEs).

Complex challenges, complete solutions

As the plastics challenge is multifaceted, so too are the solutions required. They will necessitate holistic, cross-stakeholder collaboration.

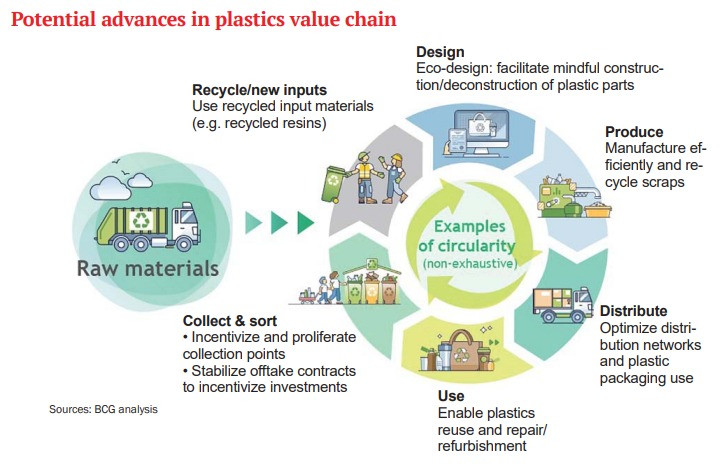

Driving a circular economy in plastics goes beyond recycling. Initiatives to advance plastics circularity can be implemented at every stages of the value chain: design, produce, distribute, use, collect and sort and recycle/new input.

There are many global examples of efforts to address this value chain that Indonesia can learn from.

At a national level, ensuring rigorous implementation and enforcement of the EPR scheme for plastics is key to boosting domestic recycling rates and providing feedstock for recycling without importing waste. Vietnam, for example, imposed mandatory EPR in 2021.

Minimum requirements for recycled content can also be implemented for selected products. In 2023, the European Union introduced legislation that all PET bottles must contain minimum 2 percent recycled content by 2025.

Introducing a similar requirement in Indonesia could not only generate demand for recycled inputs to catalyze a circular economy, but also ensure that manufacturers remain competitive in export markets that have similar restrictions.

Industry stakeholders could invest in and explore new technologies, such as advanced chemical recycling as well as bioplastics made with sustainable biomass or biodegradable characteristics. The United Kingdom, for example, committed 3.2 million pounds ($3.9 million) in a major 2023 funding announcement to innovations in plastic packaging, such as plant-based biodegradable polymers.

The Indonesian public also has a role to play. We can actively sort plastic waste for recycling to improve recycling efficiency. We can consider alternatives to single-use plastics, such as reusable cups and bags. We can also choose to support businesses that actively address plastic sustainability issues, either through eco-design processes or the use of sustainable packaging or recycled inputs.

Everyone can contribute to the effort to ensure that plastics can continue to serve the needs of society without damaging our planet. Returning to the original intention for plastics to reduce harm to nature, not amplify it, will be a more sustainable solution.

The theme for this year’s Earth Day on April 22 was “Planet vs. Plastics”, but we believe we have an opportunity here to challenge ourselves to instead transition toward the idea of “plastics for the planet”.

This means leveraging these important materials with a genuine commitment to circularity and sustainability. All it takes is willpower, creativity, collaboration and the commitment to advance plastics circularity for Indonesia.

***

Arun Rajamani is managing director and partner at Boston Consulting Group (BCG), where Kar Min Lim is principal. The authors acknowledge Alif Azan, a senior knowledge analyst at BCG, for contributing his insights to this article.