Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search results‘Family is a microcosm of nation’: Eugenia Kim on Korea, home

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

E

ugenia Kim’s debut The Calligrapher's Daughter attracted significant praise upon its publication in 2009. The story was inspired by her mother’s own, shaping a deeply personal and authentic tale.

Kim’s newest book The Kinship of Secrets is again inspired by a true story from Kim’s family. Slated to be published on Nov. 1, the book centers on two sisters, Miran and Inja, and their parents and extended families. Miran is brought by her parents to the United States, while Inja is left in Korea, under the care of an uncle and other family members. The decision to leave behind one of their daughters is evidence of both faith and devotion, but it will haunt the family for years to come.

Kim herself was born in the United States as a child of Korean immigrants. Thinking that they would return shortly, her parents left behind a daughter they only met again after ten years of separation. The story of Kim’s sister being left behind and what it was like to come to the US is the foundation of the novel.

The Jakarta Post talked to Eugenia Kim via email about writing a family story, the experience of immigrants in US and the meaning of home.

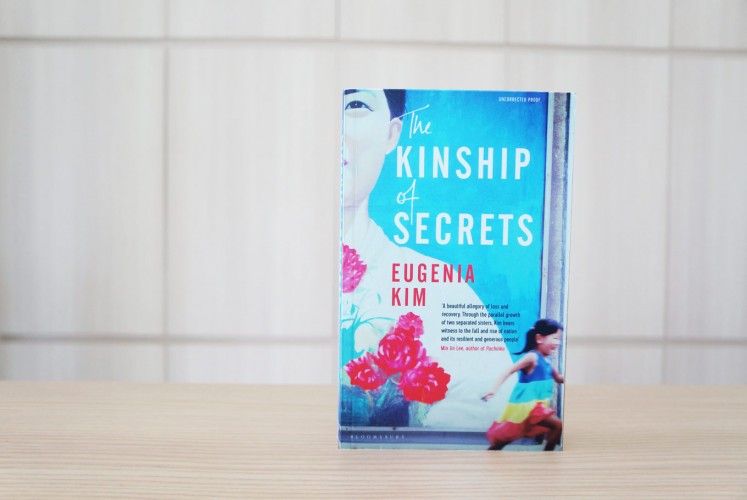

'The Kinship of Secrets' by Eugenia Kim (JP/Devina Heriyanto)Both your debut The Calligrapher's Daughter and The Kinship of Secrets are inspired by your own family's true story. What drives you to adapt these stories into fiction?

These stories were always so amazing to me as a child and continued to amaze me as I grew. They spoke of kingdoms and wars, tumultuous cultural change and the struggle for freedom from oppression. Additionally, they were a way to learn more about my family and my country of origin, since I was born in America. Though I knew about culture inherently from family and Korean community events, I knew little about Korea’s history. The more I researched and laid my family’s story against the history of the nation, the more I saw parallels of how family is a microcosm of nation. This fascinated me and drove me to dig deeper into both family and national history. And frankly, it was a way to understand my mother better by learning what she had lived through.

Are you planning to write another novel based on your family's true story?

My next novel departs from the family stories but does incorporate stories of people who were influential in my family’s life — namely women missionaries who served in Korea. The work is still too young to be talking about it.

What was the hardest part of your life upon arriving in the US? How does it differ from your sister's experience?

Having been born in the US, my life is a completely different experience than my sister’s, who came to America when she was eleven years old (in the book she is sixteen — I wanted her to be more emotionally mature). I was blithe in my acceptance of my sister; she was six years my senior, and I just assumed she was happy to be in America as many immigrants were. It wasn’t until I traveled to Korea with her for my first time in 2005 that I asked what it was like to have come to America at that young age. Her answer, that it was “the blackest day of my life,” surprised me, and led me to ask more about her life, which then became the story that inspired The Kinship of Secrets.

Read also: Book Review: A tale of two sisters in ‘The Kinship of Secrets’

You went back to South Korea in 2010. What did you feel about your travels there, and did you consider it ‘home’?

My second trip to South Korea in 2010 with my sister and other family members was both a celebration of The Calligrapher’s Daughter and a research trip for The Kinship of Secrets. At the invitation of the US Embassy in Seoul, I gave presentations and readings, and met up-and-coming Korean writers. This was an incredibly rewarding experience. The most remarkable aspect of visiting Korea, both times, was to see the homogeneity of the people, and how I physically fit in with everyone else on the street. I felt this years ago on my first trip overseas and I visited Jakarta—the unique sensation of being surrounded by my own race. But in South Korea, my gestures and personal style are so Americanized that people didn’t recognize me as Korean and asked if I were Chinese or Japanese. While my uncle was alive, there was the sense of “home” in Korea for me, but after his passing, less so.

For research, we traveled the southern route my sister and uncle, and other relatives, had taken as refugees fleeing from the second North Korean occupation of Seoul during the Korean War. We visited the hillside neighborhood she had lived in for those three years of the war, in Busan on the southernmost tip of the Korean peninsula, and discovered the church my uncle had founded. Sixty years after its humble beginnings under a hillside tent, it had become a modest stone church with a big steeple, and still had the cornerstone that combined the names of my mother and uncle as financial backers.

Your family and the fictional family in the book are Christian. How significant is religion in your life?

My father was a protestant pastor, and my mother a devoted pastor’s wife. We attended church often, both American Presbyterian church and my father’s Korean Methodist church. The church service was delivered in the Korean language, of which I had lost more and more as I attended public school, so much so that I no longer speak any Korean and understand only a little bit — mostly the language of children. There were hundreds of hours sitting on hard pews being still and entertaining myself by scrawling pictures on the program, chewing gum, or later as a teenager, reading through the American hymnals. It soured me on church service, and that and a liberal education steered me away from Christianity. Though I am no longer a Christian, I feel that as a loss and seek spirituality elsewhere.

What do you wish people would understand more when it comes to the life of Asian immigrants in the US?

That there is loss associated with the arrival. Even if, unlike for my sister, the immigration to America is a preference and a desire, there is much that is being left behind — and so much difficulty in adjusting to a new world ahead, not only in language and culture, but in basic understanding of how things operate and how people think, which can be diametrically opposed to what one is accustomed to. There is hardship, but luckily for many Asian countries, there are pockets of established immigrant communities with markets, places of worship and services that can help ease the transition. Though we are undergoing a period of oppression with regards to immigration in the U.S., I believe that most individual Americans are welcoming of migrants from any nation. (kes)

----------------

The Kinship of Secrets is available in all major Periplus outlets on Nov. 1.