Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIn Memoriam: Jeihan, he has gone home

Indonesian artist and poet Jeihan Sukmantoro spontaneously composed a poem during a talk at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara (MACAN) in April. The poem hints that he was ready for his passing.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

"Hari terang

Hati tenang

Burung terbang

Bunga kembang

Aku pulang"

(The day is bright; The heart is calm; A bird flies; A flower blooms; I am going home)

Indonesian artist and poet Jeihan Sukmantoro spontaneously composed the above poem during a talk at the Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in Nusantara (MACAN) in April this year.

Jeihan passed away at his studio in Bandung, West Java, on Nov. 29 at the age of 81. The poem hints that he was ready for his passing.

Born in the Central Java town Surakarta on Sept. 26, 1938, the artist began his career in 1953 at the Surakarta Cultural Association (HBS), where he trained under renowned painters Dullah and Soedibio.

He studied alongside painters including Srihadi Soedarsono and Fadjar Sidik as well as poets Sapardi Djoko Damono, Remy Silado and WS Rendra.

At the HBS, Jeihan was influenced by the realist and socially engaged arts that predominated in Central Java and Yogyakarta at that time (often referred to as the Yogya School).

In 1960, Jeihan continued his studies at the Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB), which was completely different to the training he had previously received. The ITB was part of the so-called Bandung School, which championed the emergence of abstract art in Indonesia.

Jeihan’s practice developed amid these two polarizing ideologies.

In 1966, after resigning from the ITB because he felt his artistic freedom was being restricted, Jeihan began to develop his own style, belonging neither to the Yogja nor Bandung schools, which placed him in a unique position within Indonesian modern art.

Jeihan is best known for portraits of people painted with deep black eyes. The lack of definition in his subject’s eyes corresponds to what the artist described as an incapacity of people to foresee the future, which related to Javanese mysticism but it also represented his own concerns and uncertainty during the political turmoil of the early 1960s.

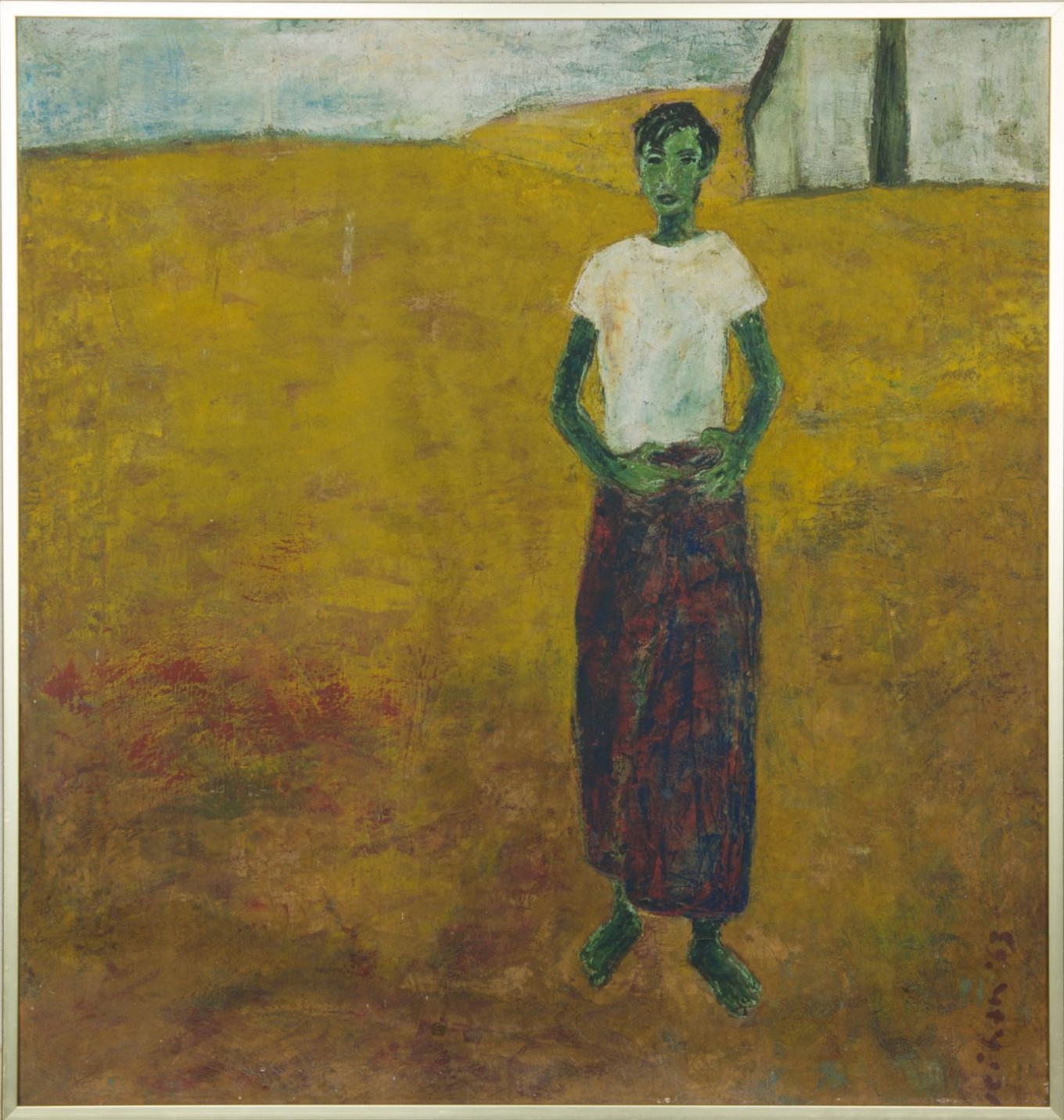

The earliest example Aku (Me, 1963) is a self-portrait created after a racial incident on May 10, 1963, in Bandung. This painting and another important early work, Gadis (Girl, 1965) were recently donated to the Museum MACAN collection.

Jeihan also published several books of poetry. He was part of a circle of poets experimenting with concrete poetry, which attempted to break from literary convention through the use of typography, visual composition and a lack of metaphoric language.

In 1971, Jeihan and fellow poets Remy Silado coined the term “Puisi mBeling” (literally translated as “naughty poetry”), to define a style of concrete poetry, which had a tendency toward conceptual art.

Puisi mBeling was published in Aktuil magazine, one of Indonesia’s first rock music magazines, where Jeihan worked as an editor from 1971-1973.

Like his portraits, his poetry reflects a desire to break away from the established artistic practice of the time and his aspiration for artistic freedom.

In 1985, following a joint exhibition with S. Sudjojono, titled Temunya 2 Ekspresionis Besar (The meeting of 2 major expressionists), Jeihan’s work became highly sought-after by Indonesian art collectors.

The exhibition, held at Jakarta’s Sari Pan Pacific Hotel, saw Jeihan’s works sell for sensational prices, higher than those of more senior Indonesian artists. Art critic Sanento Yuliman regarded this exhibition as one of the events that triggered the Indonesian art market boom in the mid-1980s.

In March 2019, Museum MACAN held a solo exhibition of Jeihan’s work, titled Hari-hari di Cicadas (Days in Cicadas), which sadly turned out to be his last.

The exhibition presented 30 portraits painted between 1963 and 1981, including some early works which had never previously been on public display.

All the portraits connected to Cicadas, a neighborhood in Bandung, at a time when Jeihan was living there, and as a whole they capture a critical period in the formation of his artistic identity. They portray the artist, family members and children; a broad cross section of figures reflecting the densely populated neighborhood.

Jeihan’s family was one of the few households that owned a television, which was considered a luxury at the time. His house became a central place for neighbors and artists visiting Bandung to gather to watch television and catch up on entertainment and current affairs.

Jeihan invited his friends and neighbors to model for him. These works display the relationship of an artist within his community, and the positive reaction to these works and the exhibition attest to the high regard the artist had in his community.

He is survived by six children and 11 grandchildren. (ste)

-- The writer is an assistant curator at Museum MACAN. He was the project leader of Jeihan's last exhibition at the museum.