Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe essence of police reform

Herman, 23-year-old student activist, died after receiving a shot to the head from a police revolverin Garut, West Java (The Jakarta Post, July 23)

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

H

erman, 23-year-old student activist, died after receiving a shot to the head from a police revolver

in Garut, West Java (The Jakarta Post, July 23). Regardless of negligence or vile intentions, police

reform is doing us shame in the international world and we’ve only seen the tip of the iceberg.

Throughout the archipelago, the public sentiment remains the same. Indonesians are abashed, ashamed, embarrassed and humiliated by our police institution whose brown uniform, unrefined manners, corrupted ethics and lack of professionalism mislead us to think that they belong somewhere with the junta in Myanmar.

The majority of Indonesians make “rent-seeking” jokes, often silently cursing, at the sight of police

offi cers as we drive by them. The more timid Indonesians readily check themselves for helmets, seat

belts, driving licenses, or ID cards just to make sure they do not have to “voluntarily” contribute cigarette money for those officers. This seems to be common practice, if not local wisdom, obtained from fi rsthand experiences in dealing with such notorious public servants.

Shortcomings in police reform are jeopardizing Indonesia’s attempts to eradicate both terrorism as well as corruption. These two priority issues rely heavily on the effectiveness of our police institution in enforcing the law and providing security.

Tempo magazine had stepped into bad terms with the Indonesian Police due to their investigative reports. At the same time, the media’s headquarters was attacked and anti-corruption activist, Tama Satrya Langkun, was later battered, possibly for his work on similar cases.

We are not jumping to conclusions that the police are guilty for all to blame, but it is obvious that they

had failed to protect our media as well as civil society activists, and had been slow in finding the culprit behind such attacks. As events unfold, the public disappointingly learned

that investigative reports had fallen on deaf ears, whistle blowers are silenced, while “internal investigations” and “semantics debates” are the weapon of choice utilized to sidestep voices demanding reform.

Why is corruption and lack of professionalism so entrenched despite police reform? Is it because

of intellectual bankruptcy, the lack of power and authority granted to Indonesia’s other antigraft institutions, inadequate leadership from the President, or the nonexistence of pressure/interest/elite groups pushing the agenda forward? (the Post, July 11, 19, 20, 21) Arguably, despite the fervor in anti-corruption rhetoric and high public expectations for police reform, there is an insuffi cient collective push from the public. The public needs to ponder whether they have made any worthwhile contribution to anti-corruption efforts. Three factors reinforce this situation.

First, although the public is well informed of reform and corruption fighting efforts, most of them rarely, if ever, provide any form of tangible support. Sadly, our “graft busters” and police reformists are fighting the long uphill battle by themselves.

When the public is not voicing themselves, individuals and institutions that do speak up are easily singled out. They become easy targets for corrupt segments within the police force that hold a vested interest in resisting or even perhaps rolling back the reform.

A previous “clash of institutions” indicates that the police institution is better established and retains

enough capacity to defame, cripple, and silence other institutions before they are even able to “leave their cradle”. However, the same clash also reminded us that public attention and support has the ultimate potential to tip the balance.

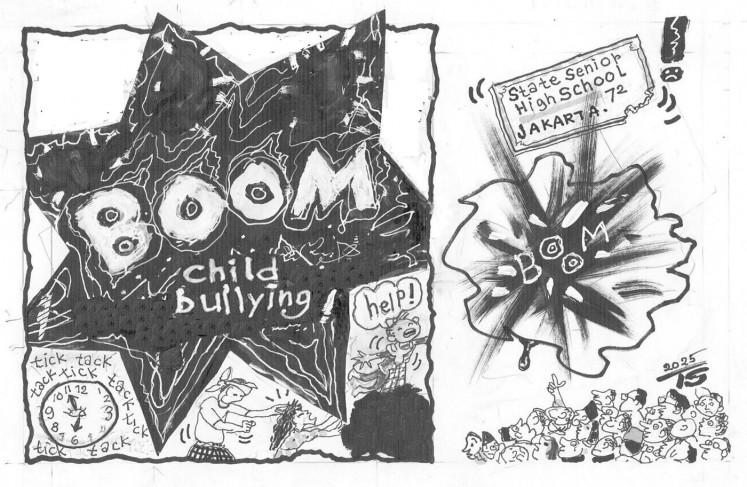

Second, existing support from the public usually fails to sustain itself. The public’s attention span on police reform and anti-corruption resembles “fi recrackers”. Cases such as the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), Susno Duadji, and Tempo’s investigative reports are examples

of such “fi recrackers”.

As soon as cases are intentionally driven into “political conspiracies to defame”, “police being the victims” and the “semantics debate”, the public loses interest while there are no public intellectuals engaged to unveil such contemptible tactics.

Third, public support often collides with many confl icting interests. Most media has an interest only

in corruption cases that “sell”.

Students, activists as well as writers are exposed to various risks every time they speak out. Policy advice from critical intellectuals are readily dismissed, while intellectuals working closely with the institution become a herd of “yes-man” apologists.

In the future, I believe that Indonesia will become one of the success stories of police reform. But before such a vision can materialize, the public needs to push as hard they can for further police reform.

The writer is a researcher at the Pacivis, Department of International Relations at the University of Indonesia.

This is a personal opinion.