Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIndonesia's unique democracy opens ways for new political theories

(JP/Hans David Tampubolon)Islam and Democracy in Indonesia: Tolerance Without Liberalism Jeremy Menchik Cambridge University Press, 2015 224 pagesDemocracy in Indonesia is apparently causing political scholars to scratch their heads in confusion

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

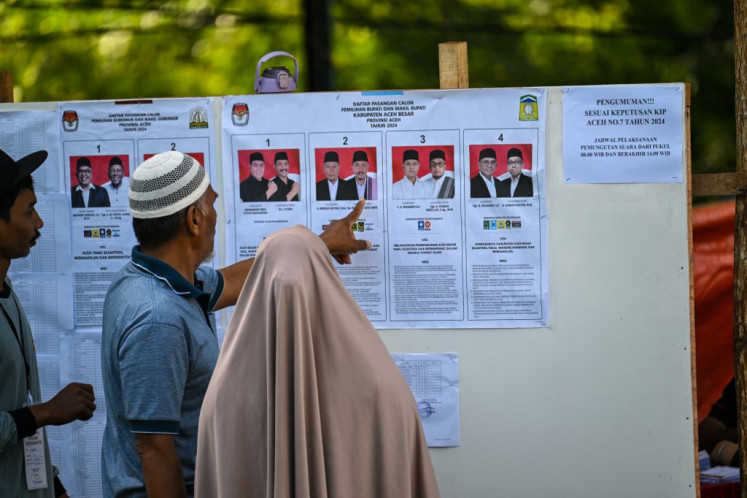

(JP/Hans David Tampubolon)

Islam and Democracy in Indonesia: Tolerance Without Liberalism

Jeremy Menchik

Cambridge University Press, 2015

224 pages

Democracy in Indonesia is apparently causing political scholars to scratch their heads in confusion.

Democratic values, such as freedom and equality, are basically common in secular states. However, this is where things become both special and confusing for scholars in analyzing Indonesia because the country is also highly religious, a characteristic outside the traits of a secular state.

To spark further discussions on the development of Indonesia's democracy, Jeremy Menchik, a professor from Boston University's Frederick S. Pardee School of Global Studies, recently launched a 224-page book titled Islam and Democracy in Indonesia: Tolerance without Liberalism.

'The book is part of a general conversation about religion and politics in the world today. It is meant to be in conversation with other general books about religion and politics. It tries to create a set of tools ' theoretical, conceptual and methodological ' on how to think about religion and modernity,' Menchik said during his book launch at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Tanah Abang, Central Jakarta.

Menchik observed the influence of religion over lawmaking in the country.

'Over the past 30 years, especially in the last 25, there have been more laws that are designed to be more muscular in terms of religiosity and attachment to religion. For example, compulsory religious education, no interfaith marriage, you cannot create a new religion, you cannot build a house of worship unless the neighbors agree, among others,' he said.

Menchik spent about eight years finishing the book. During that period, he conducted a massive number of field studies, surveys and interviews.

In particular, Menchik took a deep dive into the two largest Islamic mass organizations ' Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), which has about 50 million members, and Muhammadiyah, which has about 30 million members ' to understand how democracy can blend in with the high nature of religiosity embedded in the Indonesian society.

He said scholars believed that the Islamic mass organizations were one of the reasons Indonesia has become what he called a 'democratic overachiever'.

Historically speaking, things did not look good for Indonesia to achieve what it had accomplished in terms of democratic development. After independence in 1945, Menchik said, the Dutch did not leave much behind for Indonesia, at that time a new country.

The country has also faced numerous secessionist movements, poverty and issues related to its vast diversity. Yet, despite all of this, Indonesia has managed to consolidate its democracy and, at the same time, keep religion as a strong value in society.

'You can see that now Indonesia is a great example of a democratic success story,' Menchik said. 'It's not perfect, but it is largely a success.'

In his book, he basically tried to understand how the leaders of NU and Muhammadiyah perceive democratic values. He formulated three questions to address the puzzle. The first and the second questions were about what tolerance means to the world's largest Islamic organization, why they understand tolerance the way they do and what explains that attitude. His third question was about the implications of this attitude for democracy.

Menchik then found out that the questions were really difficult to answer because the existing theories that he had learned were unhelpful.

'So, the dominant theory is the secularization theory. This does not work well for organizations like NU and Muhammadiyah, which are very tolerant but obviously not secular,' he said.

'The second is by using theology, which is a little bit determinist, doctrine-driven behavior. This turns out to be unhelpful, too, for the very fact that there has been an enormous change in the behavior of Islamic organizations in dealing with minorities like the Christians, Hindus, Ahmadis, or the communists,' he said.

Indonesians have become significantly more tolerant toward Christians and Hindus, but the exact opposite has happened in terms of the Ahmadis and communists.

'Finally, the rational theory also does not work because you don't see as much change as you would expect.'

He later tried to explain the development of Indonesia's democracy by focusing on the decoupling of tolerance and liberalism. He argued that in order to explain the meaning of tolerance to Islamic organizations, he would need to decouple the two.

'I do this in a couple of different ways; first I do a clausal argument and I explain why NU, Muhammadiyah and their attitudes change toward minorities on the basis of local history and on the basis of ethnic groups about the role of the state,' he said.

'From there I develop a political theory with concepts like nationalism, traveling beyond their secular liberal origins. So we need to step outside the categories inherited from liberal political theory.'

Menchik concluded in the book that basically Islamic organizations in Indonesia seek a state and society where each recognizes religious freedom but is restricted from interfering in the faiths of others.

'Communal tolerance and Godly nationalism are compatible with democracy,' he said. 'Situating religious actors and agencies at the center of our analysis suggests new ways of understanding social movements, institutions and opens up new possibilities for political theory.'