Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsCases of recidivism raise concerns about early release policy

By Wednesday, authorities had sent at least 12 of the 37,000 inmates granted early release or put on parole nationwide back to prison for various crimes, including drug dealing and theft, according to the Law and Human Rights Ministry's Corrections Directorate General.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

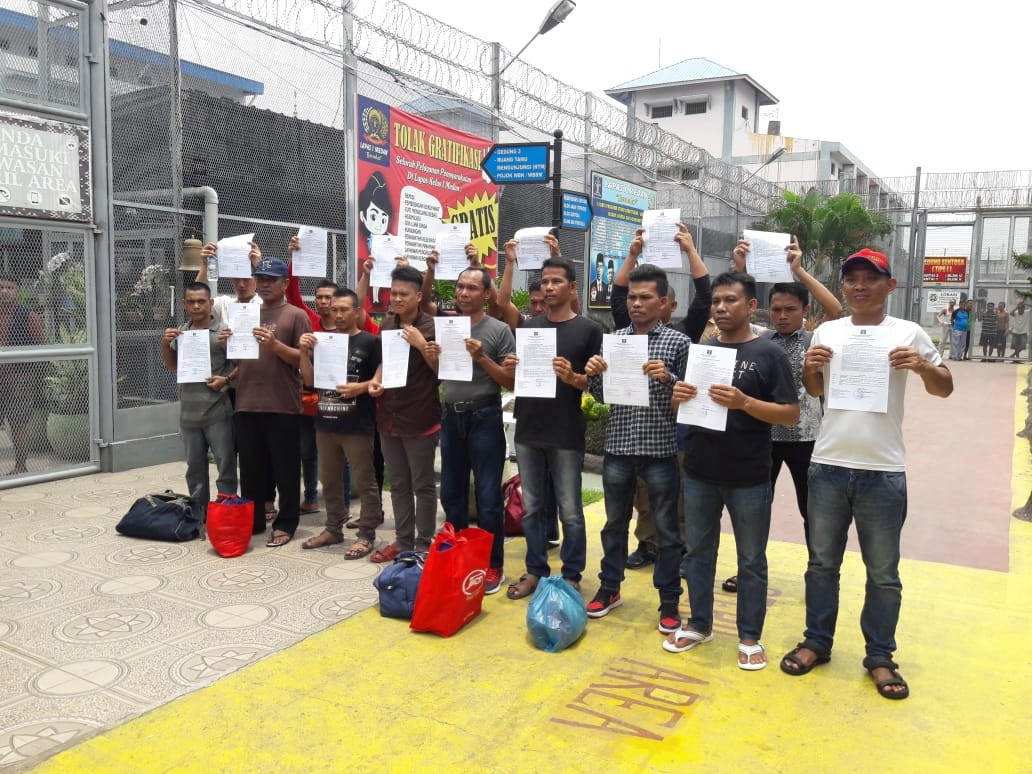

to Anyone

Inmates hold up letters confirming their release from the overcrowded Tanjung Gusta penitentiary in Medan, North Sumatra, on April 2. The government is facing scrutiny over its plan to grant inmates early release as part of its efforts to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in overcrowded correctional facilities. (JP/Apriadi Gunawan )

Inmates hold up letters confirming their release from the overcrowded Tanjung Gusta penitentiary in Medan, North Sumatra, on April 2. The government is facing scrutiny over its plan to grant inmates early release as part of its efforts to prevent the spread of COVID-19 in overcrowded correctional facilities. (JP/Apriadi Gunawan )

A

fter being released to help prevent COVID-19 transmission in the country’s overcrowded prisons, a dozen inmates have found themselves incarcerated again for reoffending, in a blow to the government's controversial early release policy.

By Wednesday, authorities had sent at least 12 of the 37,000 inmates granted early release or put on parole nationwide back to prison for various crimes, including drug dealing and theft, according to the Law and Human Rights Ministry's Corrections Directorate General.

"These 12 inmates could give a bad name to the others granted early release. However, we will carry on with the policy [of granting early release]," the Corrections Directorate General's spokesperson, Rika Aprianti, said.

The government plans to release 50,000 prisoners and juvenile inmates eligible for early release and parole to help prevent the spread of COVID-19 in crowded correctional facilities under a policy announced by Law and Human Rights Minister Yasonna Laoly on March 30. The former inmates will be under the continued supervision of the Correctional Board (Bapas).

Read also: Overcrowded regional prisons release inmates early to limit contagion

Regarding the 12 recidivists, Rika said the reduction to their sentences would be revoked and that they had been returned to their respective cells to serve their remaining prison time. If found guilty of new crimes, their sentences will be extended.

Rika was quick to deny that a lack of supervision had led to recidivism.

“We [through local Bapas] regularly monitor them via virtual meetings and video calls,” she said. “And if they are caught reoffending, we will take stern action against them.”

The corrections authorities, she said, had exercised prudence in deciding which inmates were eligible for early release or parole.

However, analysts have warned the government not to make hasty decisions in this time of crisis, arguing that reducing chronic prison overcrowding was not as simple as granting early releases or parole. A rigorous overhaul of Indonesia’s correctional system and codifications in the Criminal Code, the Criminal Law Procedures Code and other related laws like the 2009 Narcotics Law was pivotal to developing long-term solutions, experts have argued, demanding policymakers consider alternatives to imprisonment, like probation or rehabilitation.

The arrests have fueled anger toward the early release policy among some segments of the public. On Twitter, netizens highlighted the case of two inmates who were arrested by the police after mugging a woman in Surabaya, East Java, on Saturday. Both criminals were released from Lamongan prison in East Java roughly a week prior.

Read also: One inmate killed, 20 alleged provocateurs arrested in North Sulawesi prison riot

Iqrak Sulhin, a criminologist at the University of Indonesia, said that the early release order had created an additional cause for concern for an already anxious public facing a rising number of COVID-19 infections.

Many people have expressed concern that the simultaneous release of inmates across Indonesia could lead to an increase in crime or increase the spread of SARS-CoV-2, despite the fact no inmates have tested positive thus far.

Yet, Iqrak cautioned the public not to overreact to news of the reoffenders, saying it was a common problem and that the recidivism rates in Indonesia were arguably quite low. He cited data from the law ministry that showed that the country's recidivism rates for people convicted of property crimes was 21 percent, 13 percent for drug offenders and 4 percent for people convicted of petty crimes.

“Looking at the data, it’s too early to say that the policy has been a failure,” Iqrak said. “People were worried about the policy because they are in panic mode over the pandemic, so they tend to overreact over everything.”

Read also: Activists, experts caution against slapdash reform to tackle prison overcrowding

However, he warned that financial pressures caused by the pandemic, coupled with the lack of Bapas officers, could lead to some released inmates reoffending.

The Corrections Directorate General employs 613 parole officers in 75 Bapas offices across the country, which Iqrak deemed insufficient to monitor the 37,000 released inmates.

Gatot Goei from the Center for Detention Studies (CDS) called for stricter monitoring involving house visits not just video calls.

“In normal circumstances, those granted parole are obliged to report to the Bapas office once every two weeks. But during the ongoing pandemic, Bapas officers need to be more active by checking in at their homes at random times,” he said.