Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsDoubts loom over widespread use of rapid tests in virus-stricken Indonesia

More labs to run PCR tests to allow Indonesia to phase out rapid antibody tests.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he widespread use of rapid antibody tests for COVID-19 as requirements for various activities during the pandemic, including for traveling in Indonesia, has sparked concerns among experts, who called for better government control over their use.

Post-market surveillance on rapid antibody test brands used in the country carried out by the Association of Indonesia's Clinical Pathology and Laboratory Medicine specialists (PDS PatKLIn) showed that many of them had sensitivity and specificity lower than 50 percent, the association's chairwoman, Aryati, said.

"With low sensitivity, chances of false negatives are high [...] While with low specificity, chances for false positives are high," Aryati, also a professor at Surabaya’s Airlangga University, told The Jakarta Post, on Monday.

The COVID-19 task force has recommended 155 brands from various producers, as of April 28. It said it was referring to a list issued by the World Health Organization (WHO) -- which did not endorse the brands but rather inventoried lists from national regulatory agencies -- and products with certification by the European Union, the United States Food and Drug Administration and the like.

Although the varying quality of the test kits was the main problem, Aryati said how laboratory workers carried out the tests and the absence of training for these workers had also affected the accuracy of the tests.

She pointed to examples of how the incorrect volume of the samples taken, the prolonged time to interpret the results and the sampling of capillary blood, rather than venous blood, could lead to false negatives or positives. In addition, many of those who had "nonreactive" rapid test results -- indicating no virus exposure -- did not take another test within 10 days after the first one, as opposed to the prevailing protocol, Aryati said.

The PDS PatKLIn issued a recommendation on July 6 for the COVID-19 task force not to require rapid tests for travelers, citing that the possibility of false negatives and positives "could have dangerous and harmful impacts". It also recommended against requiring polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests as its sensitivity was only at between 60 and 80 percent, and given the time lag between samples taken and results announced -- which could be up to three weeks.

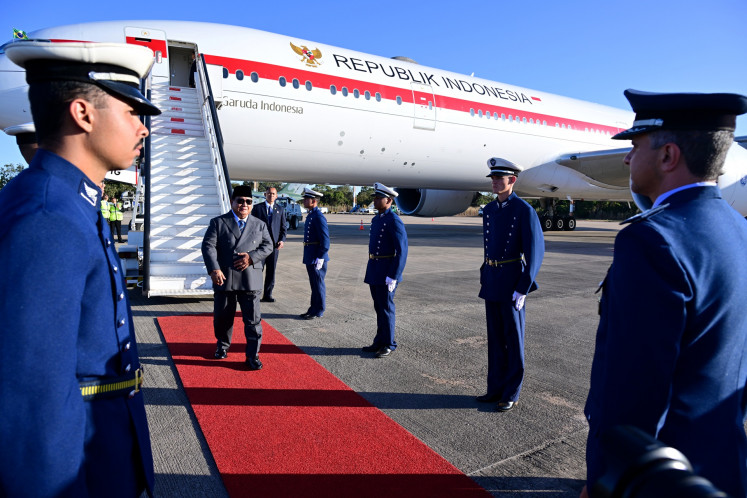

The letter was in response to the COVID-19 task force's circular issued on June 26 requiring people traveling domestically by land, sea or air transportation to present proof of negative PCR or nonreactive rapid test results that are valid for 14 days. An earlier circular on June 6 required a shorter validity period -- seven days for PCR tests and three days for rapid tests.

The association, instead, recommended using rapid molecular tests PCR (TCM PCR) or antigen tests with samples taken from travelers at ports before departure, checking their body temperature and oxygen saturation, as well as ensuring other health protocols and clean air circulation on board.

Aryati said she hoped the government would use a recent Health Ministry study on the accuracy of rapid tests and her association's post-market surveillance research to further shortlist the recommended test kits allowed to be distributed, as opposed to what she described as current "lax regulations".

"My concern is not only the transportation [sector]. There are also rapid test requirements for some participants of the state university entrance exams, or people willing to return to offices [...] I think it is concerning and unnecessary,” Aryati said.

Read also: State university entrance exams held with strict yet ‘misguided’ health protocols in place

Even though rapid antibody tests are not for diagnosis, they have now become a common requirement for some activities during the pandemic, including even for domestic violence victims seeking to take refuge in state-owned shelters. Some hospitals have reportedly also used the tests to screen patients.

"Amid the suffering, there is indeed business [of rapid tests] running here," epidemiologist at the University of Indonesia, Tri Yunis Miko, said.

He said rapid tests could aid contact tracing and surveillance efforts, especially because the government was still working on making PCR testing more accessible by adding more labs, machines and reagents. But the problem, he said, was the absence of regulations on who or which entities could administer the tests.

"There should be regulations overseeing facilities that offer rapid tests. All hospitals and clinics can offer such a service now, even small clinics, as long as they have medical staff," he said.

Following mounting complaints over the high prices of rapid tests, the Health Ministry issued a circular on July 6 setting a price ceiling of Rp 150,000 (US$10.41) for these tests.

The government's intervention should not stop at the prices but should also touch on the quality of test kits, standardization of the test performers and test availability for low-income people, said Indonesian Consumers Foundation (YLKI) chairman Tulus Abadi.

"Do not turn rapid tests into some formality or fake [procedures]. What is the point of using it if it only leads to [money] lost for consumers and is not effective in controlling [transmission]?” he said.

Read also: Victims of domestic violence struggle to access help during quarantine

The WHO, in a scientific brief in April, cited several studies that weak, late or absent antibody responses had been reported among some people who were confirmed to have COVID-19 by molecular testing, and that the majority of patients developed antibody response only in the second week after an onset of symptoms.

"This means that a diagnosis of COVID-19 infection based on antibody response will often only be possible in the recovery phase, when many of the opportunities for clinical intervention or interruption of disease transmission have already passed," the WHO said.

In the latest decree on pandemic control on July 13, the Health Ministry maintained that rapid tests were not for diagnosis, saying that in conditions where there was limited PCR testing capacity, rapid tests could be used to screen specific populations and on specific occasions -- such as travelers, including returning migrant workers. The tests could also be used to enhance contact tracing, such as in correctional facilities, nursing homes, rehabilitation centers, dormitories, Islamic boarding schools and among vulnerable groups.

The COVID-19 task force, meanwhile, said it was working on adding more labs to run PCR tests and more lab workers to allow Indonesia to phase out rapid antibody tests.