Decolonizing our conception of conflict in Papua

Indonesian officials, mainly from the TNI and police, see the armed separatists as a threat to the territorial integrity of the Unitary State of Indonesia.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he release of New Zealand national Phillips Mehrtens has yet to occur. Whether the armed wing of the Free Papua Movement (OPM) gets its way or the Indonesian Military (TNI) and National Police get involved, President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo insisted during his recent visit to Papua that the Susi Air pilot’s safety was “a top priority”.

It has been more than a month since Mehrtens was taken hostage by armed Papuan separatists operating under Egianus Kagoya. Without any clues about the pilot’s release, the rebels’ political leverage is coming to the fore with a set of demands: (a) that Australia and New Zealand bring the case of Papuan statehood to the United Nations Security Council, (b) that the UN to mediate talks between Jakarta and Papua; (c) that the International Criminal Court launches an investigation into Indonesia’s role in rights abuses in Papua and (d), the most ambitious, that Papuan independence from Indonesia be recognized.

The demands are seemingly the tail end of colonial and post-colonial conflicts. Borrowing Edward Rice’s concept of “wars of the third kind” (1999), the conflict in Papua is a conflict in which a community seeks to create its own state in a war of “national liberation” that involves resistance against domination, exclusion, persecution or dispossession of lands and resources by a post-colonial state.

Within the term, the mode of warfare is “fragmented and dispersed, involving paramilitary and criminal groups […] and the use of atrocity and siege”.

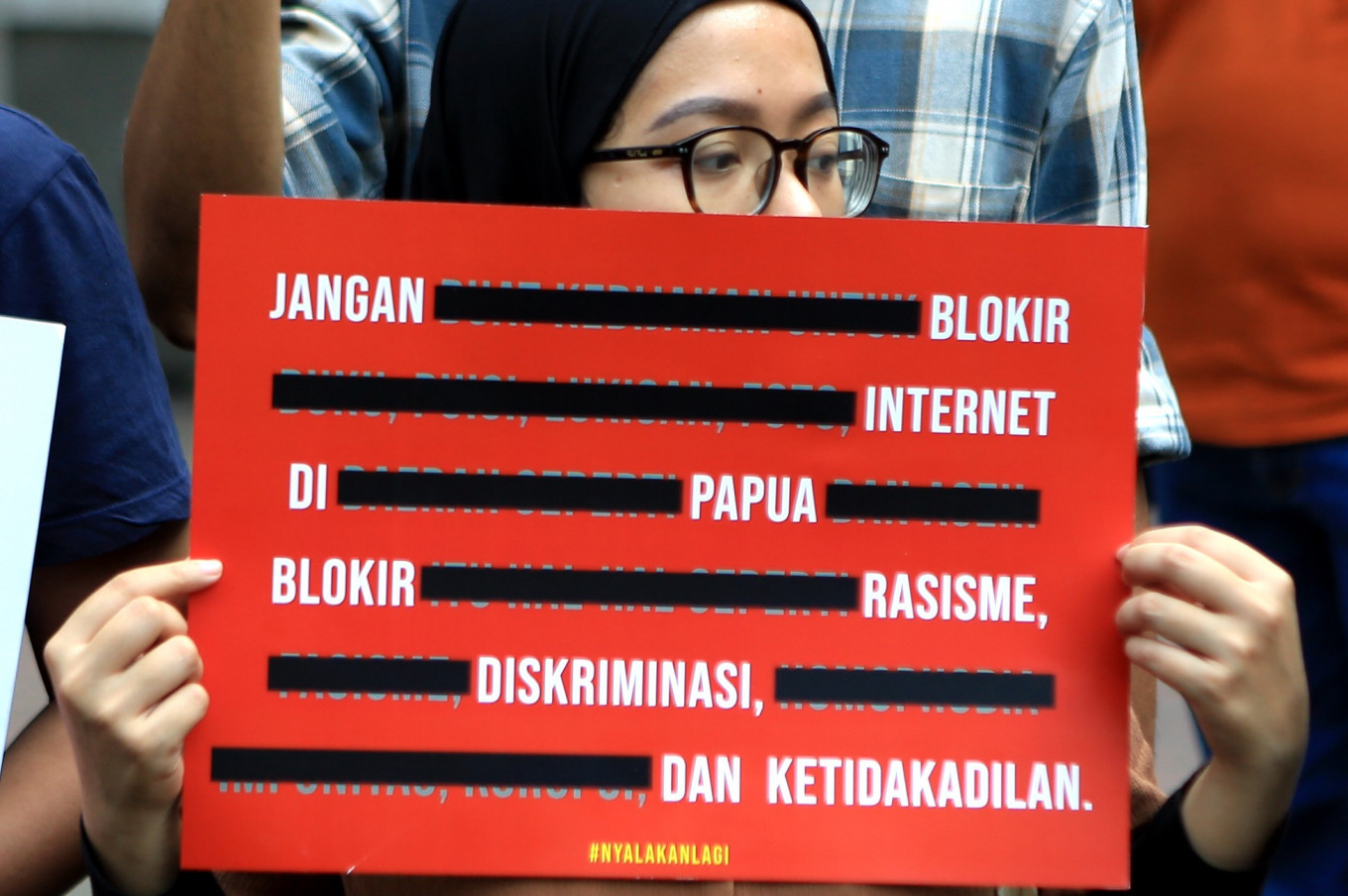

The decades-long conflict is framed by a post-colonial mindset. On one hand, Papuan armed separatists continue to argue that Papua has the right to be independent and maintain that Indonesia is a colonizer. Apart from the historical background, they appeal to the international principle of “the right of self-determination” to resist any form of presence of the Indonesian government and people in the area.

On the other hand, Indonesian officials, mainly from the TNI and police, see the armed separatists as a threat to the territorial integrity of the unitary state of Indonesia. Classifying them as armed criminal groups (KKB) or, more recently, terrorist groups does not make any difference in the way the institutions deal with the issue, which is marked by constant security operations.

The old-fashioned right to self-determination, in addition to basic rights of indigenous people as enshrined in international bill of rights, tends to lose ground and become less attractive for two or three main reasons.

First, the international structure built on the system of statehood and power games, in addition to the instrumental role of various universal and regional bodies like the UN or ASEAN, with conservative views in preferring the continuation of the existing global state-centric structure, causes claims of self-determination to gain traction only in exceptional cases.

Second, at the community level, people around the world are more pragmatic in their focus on dealing with the challenges of globalization, including socioeconomic harm resulting from the global pandemic and efforts to seize opportunities brought about by digital revolution and transnational economic activity. Within this context, the views about international society or international solidarity are more relevant to modern issues such as human, health, economic and environmental security.

Global warming, climate change, waves of refugees, interstate wars such as between Russia and Ukraine and democratization are problems that international and national governments pay more attention to and have to work on collaboratively and multilaterally.

Third, almost all nation-states and governments seek to protect their national interests. Recovery and development programs are set up and implemented with high urgency. For all these endeavors to succeed, a united, effective and functional government is a must.

With all these arguments, it is fair to say that Egianus and the armed Papuan separatists will struggle to have their anticolonial fight gain traction. There must be a strong commitment from Jakarta and regional governments in Papua to bring Papuan people better lives within the Indonesian state. “NKRI harga mati” or “Indonesian sovereignty over Papua is non-negotiable” is an old-fashioned and irrelevant slogan that must be translated into a meaningful development and progress.

With references to the Constitution and the state ideology Pancasila, national policies and affirmative development programs have to be felt and enjoyed by all Papuans, including by those with dissenting views and interests. Papua’s special autonomy law and other related laws and regulations are at the core of all the policies and programs with affirmative intentions.

There have been a number of reports, from both the academic and administrative sides, describing factors that hinder the implementation of these normative-ideal-affirmative objectives. And there is no doubt that the central down to district bureaucracies are continuing to work to solve the problems while trying to make progress in all sectors of development in Papua.

Amid the development programs, one crucial point that has been raised in almost all forums is an end to violence in Papua. There are great lessons we can learn from our own history of national independence movements, where our founding fathers had to run a long set of negotiations from Linggajati to Renville and the round table with Dutch colonists. In the post-Soeharto era, we have a historical achievement of negotiating peaceful solution in Aceh with the Free Aceh Movement (GAM).

The effectiveness and functionality of President Jokowi’s administration in resolving the conflict in Papua is ultimately indicated by the elimination of violence in Papua within post-colonial references. Pancasila and the preamble of the Constitution, which state that we are against all forms of colonialism, should be the right references instead.

In the interest of ending violence in Papua, watchdog groups need to be given space and roles to help the anticolonialial spirit really materialize.

***

The writer is senior lecturer and rector at Parahyangan Catholic University in Bandung.