Fighting illegal levies beyond organizational approach

Law enforcement against the decades-old practice might step “slowly into the light” in response to public frustration over corrupt and inefficient bureaucracy in Indonesia.

Change Size

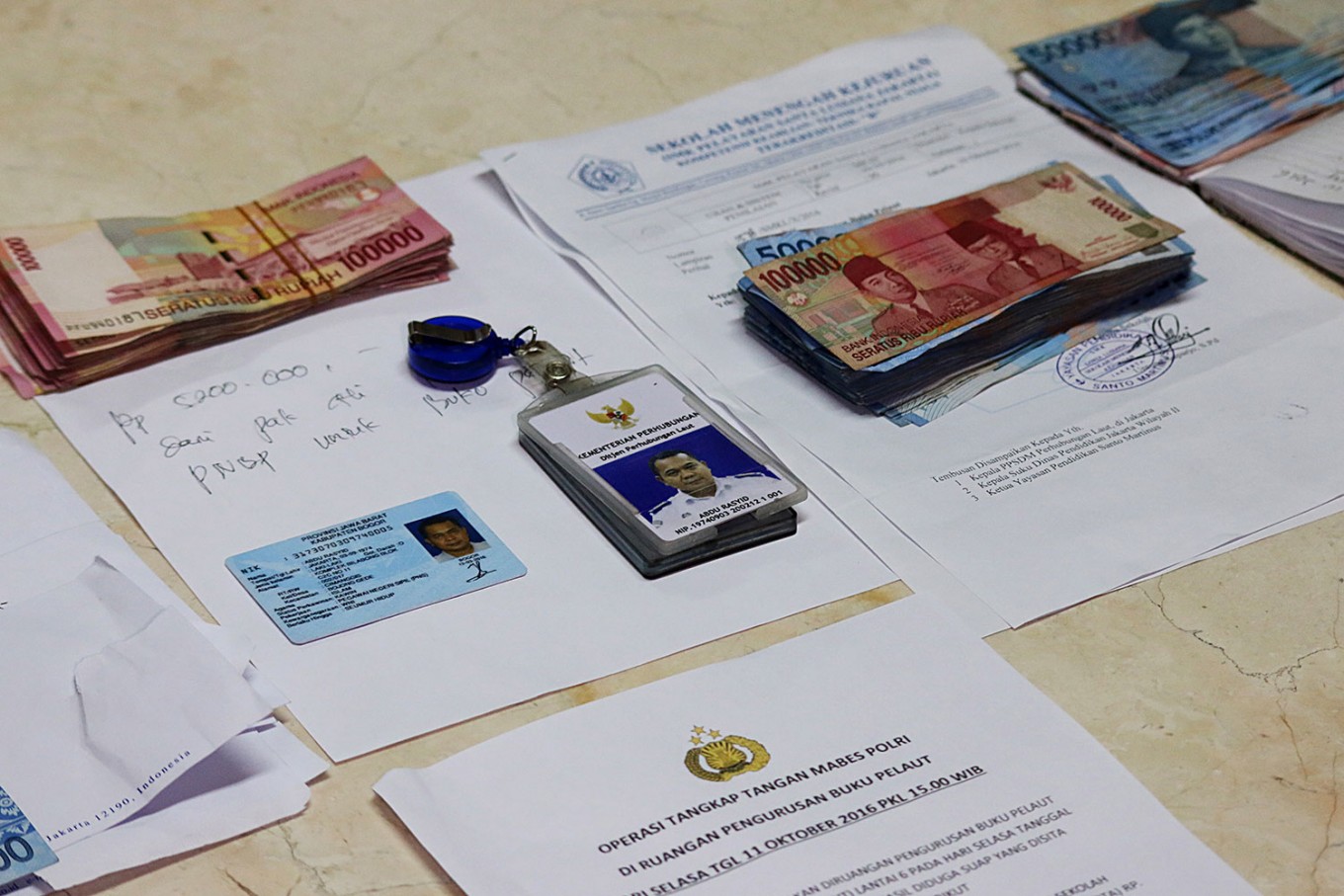

Without eradicating transactional politics, the task force mandated to combat illegal levies will only emulate the failure of the anti-illegal levy operation four decades ago. (Antara Photo/Rivan Awal Lingga)

Without eradicating transactional politics, the task force mandated to combat illegal levies will only emulate the failure of the anti-illegal levy operation four decades ago. (Antara Photo/Rivan Awal Lingga)

P

resident Joko “Jokowi” Widodo has signed Presidential Regulation No. 87/2016, which stipulates the formation of a special task force to eradicatepungli (illegal levies), reflecting his seriousness in combating illegal levies as part of his law enforcement reform agenda.

Law enforcement against the decades-old practice might step “slowly into the light” in response to public frustration over corrupt and inefficient bureaucracy in Indonesia.

The phenomenon of illegal levies must be seen not only as the non-compliant behavior of bureaucrats but also as a crime that severely impacts people’s welfare. The World Economic Forum (WEF) identifies corrupt and inefficient bureaucracy as the biggest problem for business development in Indonesia.

The WEF report also says market size is the only indicator that supports the country’s business competitiveness.

In business calculations, corrupt and inefficient bureaucracy does not matter as long as demand for products remains huge. Any cost for illegal levies can be calculated as a part of the cost of production. Suffice it to say, Indonesian consumers have to pay more due to a corrupt and inefficient bureaucracy.

Indonesians might have not been surprised when Jakarta Police arrested recently Transportation Ministry employees on allegations of asking for illegal levies.

People here have been permissive to illegal levies since they have experienced the practice themselves when accessing public services.

The government coined pungli in 1977 (see Wijayanto, 2010). At that time president Soeharto issued a presidential instruction that mandated the Administrative and Bureaucratic Reform Ministry to coordinate an operation to fight the practice. It is clear that the first official response to illegal levies was developed within the organizational framework.

Organizational theories tell us that illegal levies are an example of non-compliance behaviors of organizational members (Malloy, 2003). The lack of non-compliance detection is the root problem of compliance in an organization, such as bureaucracy.

Therefore, establishing a body that deals with detection of non-compliance behaviors is essential. Inspectorates have been playing the most important role to ensure that organizational rules are obeyed by everyone in the bureaucracy.

Today, most government bodies are equipped with an inspectorate to improve bureaucrats’ compliance.

The organizational approach against illegal levies has been implemented for almost four decades. However, the recent arrest of Transportation Ministry employees shows the organizational approach to fight the practice has failed.

Many bureaucrats simply disobey the rule at will despite the presence of the inspectorates. In other words the inspectorates fail to ensure the compliance behavior in government organizations.

Transactional services rampantly occur within or beyond the inspectorates’ detection. In the words of Krawiec ( 2003 ), establishment of the inspectorate organization serves as “cosmetic compliance”, which means a new organization is formed to respond non-compliance behavior of members but it turns out to bring no changes.

The unsuccessful organizational approach should therefore justify the use of a different approach. Some scholars have suggested that non-compliance, in particular pungli, must be understood not only as an organizational matter but also as part of institutional relationship, including political and civil society movements.

Parker ( 2006 ) introduced the concept of “compliance trap”, which refers to the lack of political support for compliance enforcement. Using this perspective we can find the existence of regulatory compliance enforcement agencies such as the National Police, Attorney General’s Office and Law and Human Rights Ministry seem difficult to produce the compliance behavior if political actors have the reverse interests in the regulatory objectives.

This argument might be appropriate to explain the current situation in Indonesia, in particular the failure to fight illegal levies.

The institutional perspective argues that illegal levies reflect the relationship between bureaucrats and politicians. John Locke imagination on the trias politica or division of power between the executive, legislative and judiciary branches is not relevant for the Indonesian context.

In this country, political actors are part of bureaucracy either within or outside the structure. The involvement of political actors in bureaucracy tends to influence professionalism and meritocracy in government decision-making processes. To make things worse, political activities follow the transactional model as evident in vote-buying practices.

Transactional politics is an enabling factor for transactional bureaucracy.

This kind of relationship explains that combating illegal levies is impossible if it only happens within organizational bureaucracy boundary.

The fight against illegal levies needs collective movements of all stakeholders. The anti-illegal levy task force will be effective only for street-level bureaucrats.

The efficacy of the task force to combat systematic illegal levies that receive strong backing from politicians remains a question mark.

Mainstreaming the movement to fight transactional politics is not an easy task and requires patience because it is a process. The educated community should collaborate with the civil society to develop a mental model for voters.

The “mental model” refers to the ability to understand the impact of individual behavior in the causalities relationship between systems such as politics and economics (Carroll and Markus, 1998).

Within the mental model, society is educated to be aware of the impacts of certain political behaviors on their daily life.

For example, the relationship between transactional politics and transactional bureaucracy tends to increase people’s expenditures both directly and indirectly.

Without eradicating transactional politics, the task force mandated to combat illegal levies will only emulate the failure of the anti-illegal levy operation four decades ago.

***

The writer, a PhD student at the University of Melbourne, lectures on social development and welfare at the School of Social and Political Sciences, Gadjah Mada University, Yogyakarta.

---------------

We are looking for information, opinions, and in-depth analysis from experts or scholars in a variety of fields. We choose articles based on facts or opinions about general news, as well as quality analysis and commentary about Indonesia or international events. Send your piece to community@jakpost.com. For more information click here.