Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsFootsteps in the sand of an emerging nation

As head of the Consultative Body for Indonesian Citizenship (Baperki), a leftist organization whose members were largely Chinese Indonesians, Tjhan was suspected of supporting the G30S.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

There were times when people like Siauw Giok Tjhan were voiceless.

Their voices only returned following the fall of the New Order military government in 1998 with the publication of several books by former political prisoners.

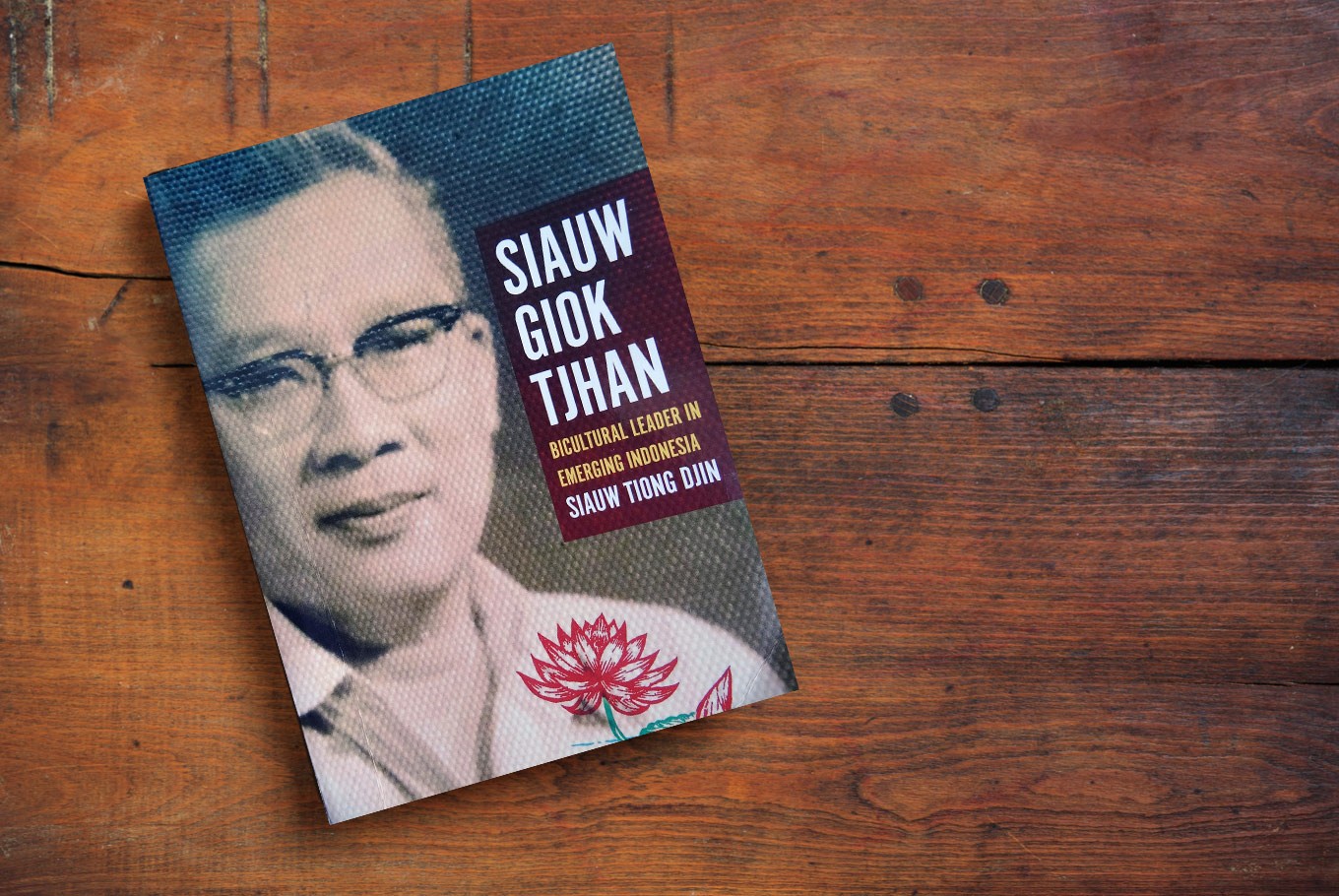

Siauw Tiong Djin’s Siauw Giok Tjhan: Bicultural Leader in Emerging Indonesiais one of them and it is refreshing to learn what he had to say.

Tjhan, who was Djin’s father, was jailed for 12 years without trial following the 1965 attempted coup, dubbed G30S (Sept. 30th Movement) by the military, which was blamed on the communists.

As head of the Consultative Body for Indonesian Citizenship (Baperki), a leftist organization whose members were largely Chinese Indonesians, Tjhan was suspected of supporting the G30S.

Tjhan claimed he knew nothing about it and the charges were never proven.

He believed that the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI), then the largest political party, was not involved. It was the initiative of individual party leaders, notably Aidit and Sjam, who attacked the army. They were alarmed by then president Sukarno’s illness amid rumors that a council of generals was preparing to oust him.

Tjhan said the involvement of the PKI leadership in the attempted coup was a “major and disastrous” mistake. There was no point for the party to do so, he said, because the political atmosphere, both domestic and international, was favourable to Sukarno and the PKI.

What followed was history.

Soeharto took power and the worst mass murder in the history of the country occurred when up to 3 million PKI members and sympathizers were killed in a couple of years. More than 100,000 were sent to prison, most of whom never faced a day in court.

The Chinese Indonesian community was attacked because the new government suspected the involvement of mainland China. Tjhan was blamed by a rival organization for the attacks and violence against G30S followers.

The Institute for the Promotion of National Unity (LPBK) alleged that Baperki’s policies and Tjhan’s communism were the onus. It held that Baperki members had been deceived by their leaders’ political direction that brought them into this disastrous situation.

Ironically, the LPKB was founded as a result of Tjhan’s attempt to protect rice mill owners who were mostly Chinese Indonesians.

In the early 1960s, a West Java governor, who was also in the military, issued a regulation which stipulated that half of all rice mills be shared with indigenous Indonesians.

When Baperki succeeded in thwarting the policy, the army responded by supporting an LPKB attack on Baperki.

Fifty-three years after the G30S, it is still shrouded mystery. Public discussions on the topic is often disrupted or banned.

Ariel Heryanto, a professor of Indonesian Study at Melbourne University, recently called the government’s narrative on the G30S the biggest hoax in Indonesia’s history.

In the absence of official acknowledgement or an apology, Djin, who was only 9 years old when his father was arrested, tasked himself to write his father’s political biography.

This 400-page book is the fruit of his work, derived from Djin’s 1999 PhD thesis from Monash University, Melbourne.

Tjhan’s life is a proof that one can be accepted, embraced and respected in Indonesia regardless of one’s ancestry, ideology or religion, when one is totally dedicated and work wholeheartedly for one’s country.

Djin divides the 15 chapters of the book into four parts starting with Tjhan’s childhood and formative years in the first two parts, and his views on various fields including economics, followed by his imprisonment, his release and his death in the Netherlands in 1981.

The book can easily pass as a study of Sukarno’s politics, not least because he was close to Sukarno but also because he was active during Sukarno’s years.

Many details in the book have either been forgotten or are has never been heard of before. For example, Indonesia had to pay the Dutch colonial government debt and reparation costs incurred during the revolution that led to independence, in line with the 1949 Round Table Conference agreement or that the first vice president, Mohammad Hatta, had been an active member of a league fighting imperialism when he was a student in the Netherlands. The league was closely associated with the Comintern whose members were mostly Marxists.

This anecdote gives rise to a question as to why communism, discarded all over the world, is still haunting

Indonesia?

Madiun Affair

The 1948 Madiun Affair was eerily similar to the G30S. The Sayap Kiri (Leftist Wing) leader Soemarsono was surprised to read stories in newspapers that he had initiated military action against government troops on Sept. 18 and that he had announced a PKI victory on the radio. Something he denied.

Tjhan believed that the affair was engineered by the Hatta government because he was eager to show the United States that his government was anticommunist.

Following the affair, the military ordered the killing of all political prisoners. Hand grenades were thrown into every prison cell. In Dampit and Magelang, all prisoners were executed by firing squads. Considered a leftist leader, Tjhan was also briefly jailed but was arrested by the Dutch a few days later.

Early on in his career, Tjhan had worked to convince the Chinese community to support the fight for Indonesia’s independence but not everyone agreed.

Those who objected said the Chinese, who lived in the republic’s territories, were often attacked by youth gangs while those who lived in the Dutch-controlled areas were safe.

Others thought they should align themselves with China as it could protect them when they were in danger. The issue of safety seemed to have divided the community into supporting the Dutch, China or Indonesia.

Tjhan did not shy away from pointing out that some Chinese felt they would downgrade their social status when they aligned themselves with Indonesians.

This division was partly responsible for anti-Chinese policies and attacks in independent Indonesia.

One of Tjhan’s notable achievements in the early 1960s was to maximize the number of Indonesian citizens of Chinese descent who became Indonesian citizens (p. 164, 165).

_______________________________________

Siauw Giok Tjhan: Biocultural Leader in Emerging Indonesia

Author: Siauw Tiong Djin

Published: 2018

Publisher: Monash University Publishing, Melbourne

Category: Political biography

Pages: 400