Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIs freedom of religion conditional in RI?

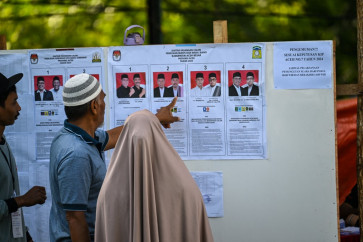

Kingdom of Eden members hold a picture of their leader, Lia Aminudin, outside the Central Jakarta District Court, where she was tried in 2006

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Kingdom of Eden members hold a picture of their leader, Lia Aminudin, outside the Central Jakarta District Court, where she was tried in 2006. (JP)

In the first few days after an Ahmadiyah mosque in Parakan Salak, Sukabumi, West Java, was burned down by a mob of hardliners at the end of last month, Siti Masitoh had to stop her 6-year-old son from running out from their modest house to the mosque for dusk prayers.

Locking the door, the wife of the leader of Parakan Salak's Jemaah Ahmadiyah, Asep Saifudin, told her son in tears that the Al-Furqon mosque was no longer there.

"It's like he forgets the mosque has been burned down," Masitoh said last Sunday.

When he does remember, he cries and asks his parents to rebuild the mosque, which is now in ruins. Its roof and dome collapsed in the fire.

On the evening of April 28, a group calling itself the Jamaah Al Mubalighin Communication Forum set fire to the mosque, which belongs to the Ahmadiyah sect.

The attack was carried out less than two weeks after a governmental Coordinating Body for Monitoring Mystical Beliefs in Society (Bakorpakem) recommended Jamaah Ahmadiyah to be outlawed.

The board, consisting of representatives of the Attorney General's Office, the National Intelligence Agency and the National Police stated that the group had "deviated from Islamic principles" for believing that Muhammad was not the last prophet of Islam, contradicting mainstream Islamic tenets.

Ahmadis believe Punjabi Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who founded the Ahmadiyah group in 1889, is a prophet and also the messiah.

Two days before the attack, ulema in the area demanded the Ahmadis close the mosque and repent publicly. If they did not, the ulema said they would not be responsible for what happened next.

Confused, Asep asked for more time to think and to wait for the central government's decision on Ahmadiyah. The fate of the group has yet to be determined by a joint ministerial decree -- jointly drafted by the religious affairs and home ministries, as well as the Attorney General's Office.

The mob however, could not wait.

The burning of the mosque in Sukabumi is the latest in a string of incidents of harassment and violent attacks against Ahmadis across the country. From the southern part of Indonesia (Bengkalis in Riau) to the eastern part (Bulukumba, South Sulawesi), the persecution of the Ahmadis has been widespread. It has been common for mobs to destroy the houses of Ahmadiyah members.

In Mataram, Lombok, East Nusa Tenggara, some 192 people are still living in a refugee center after being forced out from their village in Lingsar, West Lombok, two years ago. More than 300 houses there were destroyed.

As the most populous Muslim-majority country, Indonesia has been known for its religious tolerance. The state recognizes six official religions: Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism, Catholicism, Protestantism and Confucianism. A decade after reformasi, the pluralistic country, however, has been witnessing the growing political power and influence of religious zealots, threatening religious minorities' freedom to practice their beliefs.

According to Ahmadiyah spokesperson Syamsir Ali, the campaign against Ahmadiyah escalated in the reformasi era, after the fall of the authoritarian New Order regime. Ahmadiyah entered Indonesia in 1925, establishing itself legally in the country in 1953. The Indonesian Council of Ulema (MUI) issued a fatwa branding Ahmadiyah as "deviant" in 1980 and re-issued it in 2005. The iron rule of Soeharto, however, did not give way to any social unrest.

"In the New Order regime, I guess because Soeharto emphasized national stability, people could not act on the MUI's fatwa," Syamsir said.

Terror and intimidation by hardliners were not directed at Ahmadiyah alone. Violent attacks were also faced by other sects that were deemed "deviant" by the Indonesian Ulema Council. Mobs harassed and attacked members of the Kingdom of Eden sect in Jakarta founded by Lia Aminudin, who claimed to receive revelations from the Angel Gabriel.

In Bogor, mobs also intimidated members of Al-Qiyadah Al-Islamiyah, founded by Ahmad Mossadeq, who claimed to be a prophet and the messiah.

Under the 1945 Constitution, the state "guarantees all persons freedom of worship, each according to his own religion or belief".

Syamsir said that despite the Constitution's guarantee, the state's intervention in religious affairs had increased during the tenure of President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono.

"In Megawati's time, the head of radical group FPI, Habib Rizieq, was arrested; In Gus Dur's (Abdurrahman Wahid) time he received the Jamaah Ahmadiyah leader as a guest," Syamsir said.

In Yudhoyono's tenure, amidst pressure from radical groups, the state acted aggressively in banning sects deemed "deviant" and putting religious sect leaders behind bars.

Last year, after a recommendation from Bakorpakem, the state banned Al-Qiyadah Al-Islamiyah. Mossadeq has recently been sentenced to four years' prison for blasphemy,

The state also intervened in the case of the Kingdom of Eden sect. Lia was sentenced to two years' prison in 2006.

Police have acted quickly in capturing Lia and Mossadeq, however, law enforcement over the attackers was almost non-existent. None of the attackers of the group were taken into custody. In the 2006 attacks against Ahmadis that left hundreds of people homeless, only four people were brought to trial. They served two months in prison.

In the case of the mosque burning in Parakan Salak last month, Asep said the state apparatus -- sub-district head, the police precinct chief, and the military command -- acted as the ulema's mouthpiece, delivering the threat to the Ahmadis there.

The Sukabumi Police resort chief Adj. Comr. Ghuntor Gaffar confirmed this: "Yes, they delivered the ulema's demand to the people of Ahmadiyah," he said, adding that they were aware of the threat written in the ulema's demand.

"However, the police at that time sent personnel to secure the mosque," he said. Some six personnel were deployed to guard the mosque and 20 police guarded the streets leading to the mosque.

Some regional administrations, such as Sukabumi, Kuningan, and Cimahi in West Java, as well as administrations in East Nusa Tenggara, have banned the Islamic sect Ahmadiyah.

Moderate Muslims and human rights activists have been appalled by the state's intervention, deeming it against human rights and unconstitutional.

Bakorpakem spokesperson Wisnu Subroto, however, said critics had interpreted the Constitution wrongly.

"The state guarantees all persons freedom of worship, each according to his own religion or belief, which means, if one chose to have Islam as his religion, then one is free to worship according to Islamic teachings, the same goes if one chose Christianity," he said.

"It is not right to have chosen Islam as a religion but then freely interpret and modify it," he said.

Legal Aid Institute director Patra M Zen, a member of a National Alliance for Freedom of Religion and Belief, said the state should not intervene in the religious life of its citizens.

According to Patra, the heart of the problem was contradictory legislation.

He pointed to a 1965 presidential decree on the Prevention of the Misuse and/or Besmirching of Religion, which was issued by then president Soekarno during the "guided democracy" era, as the core problem, aside from the growing political power of religious extremists and the indecisiveness of the government.

The decree prohibits personal interpretations of existing religions in Indonesia (i.e Islam, Catholicism, Protestantism, Buddhism, Hinduism and Confucianism) that defy the tenets of those religions. Bakorpakem based its recommendation to outlaw "deviant" sects on this decree.

The issuance of the decree in 1965 also resulted in the addition of an article on blasphemy in the Criminal Code, which brought Lia and Mossadeq to prison.

"The problem in this piece of legislation is the state holds the authority to determine which belief is right or wrong by giving the mandate to the Religious Affairs Ministry and the Attorney General's Office," he said.

Patra said the alliance was currently preparing a draft for the judicial review of the decree.

"We're seeing a step back in religious tolerance and pluralism in SBY's time," he said referring to Yudhoyono's popular nickname.

"What we need to hear from the President is a firm statement that the state will create religious tolerance, uphold the rule of law, and facilitate religious dialogue between groups," he said.