Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsJumilah: Against illiteracy

JP/Panca NugrahaOnce an illiterate woman, Jumilah has now become a pioneer ineducation, working to eradicate illiteracy in West Lombok’s Batulayarvillage

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

JP/Panca Nugraha

Once an illiterate woman, Jumilah has now become a pioneer in education, working to eradicate illiteracy in West Lombok’s Batulayar village.

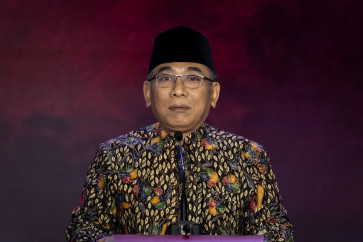

She sent a handwritten letter to the governor of West Nusa Tenggara province, HM Zainul Majdi, asking him and a group of provincial government officials from West Nusa Tenggara and West Lombok to visit the school she set up in the remote area of Duduk in October this year.

“I apologize if the words used in my letter were unrefined and unpleasant, but I really wanted the governor to see the situation for himself, and not just rely on information from other people,” said Jumilah, when the governor and his officials finally came to visit her alternative informal school, a modest six-meter-squared building with a roof but no walls.

Who would have thought that since 2004 dozens of school dropouts would have returned to this school to build their knowledge, and that Batulayar villagers who were once illiterate would have learned to read and write?

Thirty-year-old Jumilah was brought up in a family of farmers, married off at 14, having barely completed primary school. But she never stopped wanting to learn to read and write. When her eldest daughter, Diana Suryani, started elementary school, Jumilah found herself learning along with her child.

“I could read and write after my daughter Diana entered the second grade in 2004,” she told The Jakarta Post. According to her, many children weren’t as lucky as Diana at that time because their parents were reluctant to send them to school, claiming it was too far away and a waste of time.

Once she learned to read and write, Jumilah became eager to pass her knowledge on to her neighbors and the community members around her house who were still illiterate. So she began teaching her neighbors the letters of the alphabet.

A number of tourists who took an interest in Jumilah’s activities donated books and stationery. Some of them were also keen to help as seasonal tutors.

In the middle of 2004, with the help of an ACCESS aid program and a number of local non-government organizations (NGOs), Jumilah established the Kahuripan Institute, a community-learning group that became her pioneering school.

When she first opened her school, 100 students attended classes, consisting of 50 illiterate adults and 50 young dropouts living in the Duduk remote area and neighboring communities in Batu Bolong.

“We call this an alternative school because we are not just teaching students to read and write, but we’re also showing kids how to interact with nature,” said Samidin, 27, one of the tutors in Jumilah’s School, when talking to the Post.

The Kahuripan Institute has how established four other educational posts in the remote areas of Penanggak, Batu Bolong, Duduk and Batulayar.

Classes take place inside the school as well as in the field, with students going to the beach and the forest.

“In the past, many people from our communities used to cut down trees in the forest, But now that we have educated them about the importance of the forest and conserving the environment, they no longer do that,” she said.

Jumilah’s school expected little support from the government. According to Jumilah, until 2009 the government had never assisted the school. The only aid came from the ACCESS NTB program, the Tunas Alam (natural shoots) Indonesia Foundation and a number of tourists.

Jumilah’s progress encouraged ACCESS NTB to help her when she was invited to Makassar, South Sulawesi, in August 2009, to share her experiences with a local learning group. Her school thus became a pilot project.

Governor Majdi would have probably never set foot in the remote area if it weren’t for Jumilah.

“I love to visit rural areas where there are real achievements and something that can be replicated in other villages. All that has been done by Jumilah,” he said.

Governor Majdi said he was proud Jumilah and the Kahuripan Institute had helped build a self-supporting education program in the village.

“They implemented their own initiative without hoping for any government assistance. Not only did they build roads and bridges, but also educational institution,” he said.

After Governor Majdi’s brief visit, the provincial government granted the school an educational fund of Rp 5 million (US$500), as its policy is to encourage education and health initiatives.

Since early 2009, the provincial government of NTB has handed out educational aid to at least 164,955 poor students of elementary, junior, and senior high school level, covering eight regencies and two cities.

Every poor student receives assistance to meet his or her education costs, ranging from Rp 30,000 ($3) a month for elementary-level students to Rp 65,000 a month for students at high school level.

The total provided through the 2009 NTB state budget amounts to more than Rp 240 billion ($24 million).

The NTB provincial local government, which is fighting to give poor students access to free education and reduce the illiteracy rate, announced a 12-year compulsory education program in the province of Nusa Tenggara for the 2009-2013 period.

The provincial government has also poured more than Rp 30 billion ($3 million) into the state budget toward educating around 285,000 illiterate people in the NTB population aged above 15.

Although these huge funds should ensure that children can go to school, it does not guarantee they will, if their parents are not aware of the need for education.

“For Jumilah, the most important thing was showing the community the importance of education. The children are now all attending school,” said Abdulrahman, the executive field officer at the Tunas Alam Indonesia Foundation.

Yet Jumilah, whose reputation has now extended to areas she has never visited, is still a simple village woman, with simple dreams.

“I just want illiteracy to be eradicated, and children to attend school,” she said.