Economics and security of global supply of coal

Globally, coal, with its gasification technologies, appeared in the early 19th century

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

G

lobally, coal, with its gasification technologies, appeared in the early 19th century. The discovery of petroleum and gas and 100 years of declining prices, however, has hindered the demand for coal-based synthetic fuel conversion.

In the 1970s, the only significant markets remaining were metallurgical and large boilers used mainly for electricity generation. Conversion inefficiencies contributed to the reduced global demand — made worse by the use of low-grade coal.

Nevertheless, due to the larger known resources and reserves of coal, compared to crude oil and gas globally, and the current trend of higher world oil and gas prices, coal will continue to hold promise.

The report endorsed by Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2007 — The Future of Coal: Options for Carbon-Constrained World — was convincing. Coal will again play a significant role in any future world energy scenario.

A continuous increase in global demand will trigger world coal prices. By 2050, MIT suggests that world coal prices are projected to increase by 47 percent in the US and by much more in China, i.e., 60 percent.

Although currently there is no consensus on the trend increase of the world coal price, Citibank projects prices of US$180/tons FOB by 2015.

The American Energy Information Administration’s latest data shows an increase of 5 percent a year.

The growing need for electricity in China and India will drive global demand, even when, due to carbon tax, coal demand in Europe will decline.

At this moment, China is installing two to three new coal-fired power plants per week with capacities of 500 to 600 MW per plant, and has plans to continue at that pace for at least the next decade.

US demand for coal will also increase significantly, but will mainly drive increased coal production in the United States.

Coal has the advantages of the least cost and a great abundance. MIT indicates that coal can provide usable energy at a lower cost, between $1 and $2 per MMBtu (1 million British thermal units), compared to $6 to $12 per MMBtu for oil and natural gas.

The abundant coal resources are distributed in regions of the world other than the Persian Gulf, the unstable region that contains the largest reserves of crude oil and gas.

The US, China and India have immense coal reserves. For them, as well as for importers of coal in Europe and East Asia, economics and security of supply are significant incentives for the continuing use

of coal.

As in the 1970s, most coal today is used to generate electricity, and as the global economy grows, so does their demand for electricity.

The need to use electricity to replace some of the energy lost due to the decline of oil and natural gas will put yet more upward pressure on the global demand for coal.

As the global demand continuously grows, so does the global supply. Statistics say that the global coal production will substantially increase over the next 10 to 15 years, mainly driven by Australia, China, former Soviet Union countries, such as Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and South Africa.

Known reserves of approximately 1 trillion or more metric tons exist in these countries.

However, this stable growth — and only up to a certain period after that — will likely be compatible with the world policy scenario, in which coal production is constrained by climate policy measures. MIT projects a window of 50 to 75 years, world coal production will then reach a plateau and will eventually decline thereafter.

It is true, for the same amount of energy released, coal produces more carbon than either oil or gas.

Mounting pressure to reduce coal use cannot be avoided then, as global warming begins to have serious global effects.

Unfortunately, due to its abundance and the world’s urgent need to replace some of the energy lost from the depletion of oil and gas reserves, the decline in coal use will not be as dramatic as with those fossil fuels.

Carbon-free technologies, chiefly nuclear and renewable energy for power generation, will also play an important role in our carbon-constrained world.

However, in the absence of a technological breakthrough, coal, in significant quantities, will remain indispensable.

“Fundamental research in coal liquefaction and gasification, IGCC, and CCS needs expansion, as they are among our most promising future technologies.”

In both a constant coal price scenario, but even more so under a scenario where the price of coal will increase, we have a significant opportunity to add value to our abundant coal resources, rather than only export the raw material.

Our reserves have currently reached 105 billion tons, with a predicted production level of 530 million tons in 2050. The depletion of our oil and gas resources provides an opportunity for liquefied coal and coal gasification.

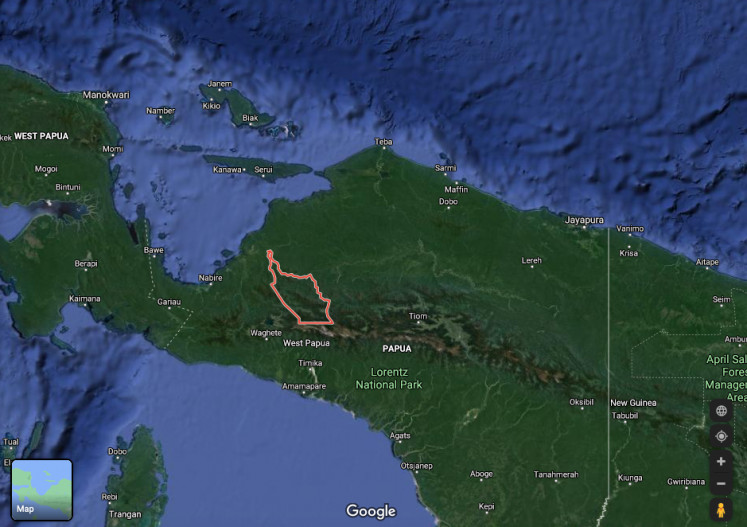

Based on three mining sites, in South Sumatra and Kalimantan, research on low-grade, brown coal liquefaction concluded that as much as 4.5 barrels of crude synthetic oil was found to be equivalent to 1 ton of coal.

A coal liquefaction plant with a capacity of 6,000 tons per day can contribute to national fuel production, adding up to 2 percent.

If 10 plants or more are constructed, this crude synthetic oil can provide approximately 20 percent of the total national fuel production — a significant contribution. The price of crude synthetic oil can be as low as $40 per barrel, which is much less than the current price of crude oil — competitive enough.

Although liquefaction is energy-intensive, in a low-priced-coal scenario, the energy can come from coal-fired electricity, and under a high-priced-coal scenario, the energy can come from our other abundant resources, i.e., geothermal.

MIT recommends options of coal combustion technologies combined with an integrated system for CO2 capture and sequestration, which is another measure we can follow.

This is challenging — based on experience elsewhere on the Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC) — it will, however, take 10 years or so to master these technologies.

Many hopeful words are being heard globally about the possibility of alleviating CO2 emissions by implementing Carbon Capture and Storage (CCS).

However, this technology is still in the experimental stage, and there is much skepticism surrounding the security and economics of storing such enormous quantity of CO2 in porous rock strata.

Our dependency on coal for decades ahead is indispensable. Worse, this is likely to involve a massive increase in low-grade coal production, as more than half of our reserves are low-grade — possessing a high water but low calorie content and higher ash disposal — producing more CO2 per ton of coal.

This is where an Annex I country needs to step in. Fundamental research in coal liquefaction and gasification, IGCC, and CCS needs expansion, as they are among our most promising future technologies.

What is needed is a Project Apollo for coal — sizeable and global coordinated efforts to acquire clean coal knowledge, without which we are doomed to stall.

The writer is director of energy, minerals and mining at Bappenas (National Development Planning Agency).