The Paris agenda and its political obstacles

Representatives of 91 countries and 26 donor organizations declared the Paris Declaration when they met on March 2, 2005

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

R

epresentatives of 91 countries and 26 donor organizations declared the Paris Declaration when they met on March 2, 2005. The consensus was to generate the best strategies to enhance aid effectiveness in developing countries. It was designed to rectify previous mechanisms; for example, conditionality and adjustment programs, which were deemed unable to successfully develop a constructive relationship between aid recipients and donors.

The main idea behind the Paris declaration was to increase the sense of belonging among aid recipients by giving them more authority to set up program objectives according to their own domestic context. At the same time, donors and aid recipients had to align their voices and interests regarding arranged objectives. That relationship must embed the principle of mutual accountability so that each party can uphold transparency on the use and achievements of the program.

Fast forward eight years and the materialization of the agenda has been far from successful: Indonesia being no exception. An assessment on the progress of implementation of the Paris declaration for Indonesia describes that only five out of 13 indicators had met 2010 targets (OECD, 2011).

Many factors have slowed the implementation of the Paris agenda. On the one hand donors are responsible for not completely handing the authority to recipient governments. To be precise, some accuse the donors of reluctance to cede their authority as they still want to impose their agenda inside the aid partnership (Rosser and Simpson, 2009). On the other hand, recipient governments face a lack of capacity in managing large amount of aid (Smillie and Lecomte, 2003).

However, in those views, the obstacles of aid delivery are seen as a mere technical-administrative matter rather than an activity involving powerful relationships and competing interests. In the latter, aid is understood as “a project” that needs sufficient political ground for aid to produce the best outcomes. The absence of a required political base only creates “political obstacles” for an aid funded program to flourish. The obstacles of aid delivery in Indonesia should be seen in a similar fashion.

Political obstacles can be perceived in several ways. First, it can manifest as the difficulty to form democratic political coalitions. Democratic political coalition is important because only through it can aid have diverse control points by which accountability can be preserved. Certainly, bringing together the involvement of bureaucrats, House of Representatives members or NGO activists does not guarantee democratic aid management since it is without democratic creed. Unsuccessful aid missions in failed states are a good example of this argument.

Consequently, there must be an alliance of democratic interests among domestic actors that agree to support aid implementation in a transparent and accountable manner. Aid management must not be touched by the predatory interests that crave to hijack aid for the reinforcement of their political position.

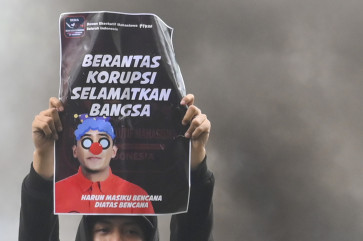

Referring to recent cases, the fact that ministries led by political party members have been entangled in corruption scandals makes the problem even more pressing for Indonesia. It is hazardous if aid is coordinated by those interested in capturing public funds. Even more dangerous if such predatory interests are not moving as a singular unit or small group but as a coalition of interests interested in looting public money.

Second, political obstacles can take shape as the lack of legitimacy from non-state actors. It is widely understood that in a democratic system, legitimacy is decisive if a policy, especially if it is related to aid. It is very much related to the way the programs are constructed. In this regard, we are familiar with two approaches in policy making: “top-down” and “bottom-up”.

Nowadays, the top-down approach is obsolete. Its implementation in aid management can be framed as “elitist” in the sense that it rarely involves grass root groups from the very beginning. Instead, the design only accommodates knowledge from the bureaucrats and consultants who perceive aid recipient as “the target” without a role in the design of the program. This can reduce trust from community toward aid bureaucracy, often leading in turn to a lack of support and legitimacy in program implementation.

Nevertheless, the bottom-up approach is not completely problem-free. Although mechanisms such as the “deliberation of development planning” (musyawarah perencanaan pembangunan — musrenbang) have been introduced to induce participation from below, its usage is misused as a tool to fortify local elite power (Rodan, 2013). Moreover, public participation might be ridden by predatory interests seeking to take over aid disbursement for their own benefit.

Selecting certain groups to participate is not the solution. The alternative is to build mechanisms by which potential ideas can be scrutinized and criticized before being incorporated into the program. The basis for building those mechanisms should be the principles of transparency and accountability.

To conclude, one year before the elections, stakeholders of aid management organizations should be aware that they need to form a long-term commitment to institutionalizing support for aid delivery. Bureaucracy, political parties and NGOs should form a coalition. However, each must devote the same commitment to transparency and accountability to its role.

The writer is an alumnus of the Institute of Social Studies (ISS), the Netherlands.