Constitutive elements of distrust toward non-government organizations

A recent survey reported that popularity of NGOs (non government organization) is declining in Indonesia (The Jakarta Post, April 26)

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

recent survey reported that popularity of NGOs (non government organization) is declining in Indonesia (The Jakarta Post, April 26).

According to Edelman Trust Barometer, public confidence toward NGOs decreased from 61 percent in 2011 to 53 percent (2012) and, finally, to 51 percent this year. Those numbers are below the average global level of 63 percent.

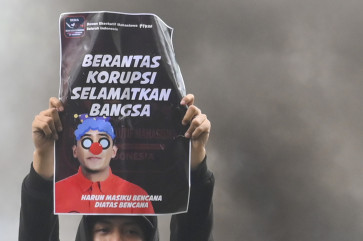

When asked about NGOs, Indonesians usually react: 'Oh, you are those who always protest on the street!' That popular image is not wrong at all. To mention a few of them, there is an image of NGOs as a group of people who carry out a 'holy' mission to advocate social developments. Despite such a positive image, there is also a picture that portrays negative impressions of NGOs as an organization that sometimes resort to violence.

By definition, NGO refers to a non-profit oriented organization which works independently from the government (Merriam Webster). It is commonly interchangeably used for other words such as civil society organization, voluntary organization or in Indonesian the popular term, Lembaga Swadaya Masyarakat (LSM).

Various definitions of NGOs represent different historical backgrounds (Lewis, 2009). For instance, 'non-profit organization' is a popular term in America because of the dominant role of a market that needs clear distinguishable labels between profit-oriented organization and non-profit organization.

What makes them interchangeable is the fact that they dwell in the civil society realm. Following Antonio Gramsci, this realm comprises private entities ranging from political organizations, churches to families. In contrast, political society is the sphere composed by state organs that have missions to maintain order.

Different images of NGOs signify a deeper problem since they are constituted by different realities of how the work of NGOs is assessed by the public. In this sense, the low trust should be examined through its constituting elements: the historical and political ties.

______________________

Unconsciously, NGOs have been expanding and sustaining the international organization's agenda.

Historically, NGO was officially admitted in 1945 when article 71 of the United Nations charter stated them as a part of the support of UN activities.

However, the term became more associated with aid business when in the 1980s the donor industry

exploded. To cope with development issues at that time, the donors felt that participation from the public was necessary to enhance aid deliveries.

To accentuate the actors that embody the principle of participation, donors revitalized the term NGO and dragged it closer to aid industry's agenda. Therefore, the word NGO is necessary identification to support aid disbursement, particularly in developing countries.

The close relation between NGOs and the aid industry forced the first to be more professional and more attentive to jargon such as 'transparency', 'accountability', 'strategic planning' and 'logical framework analysis'.

The consequences can be defective since domestic NGOs might be: first, potentially detached from their communities and second, only act as the implementer of donor's agenda.

The first consequence is much related to the capacity of NGOs that failed to produce significant transformation in the community they work with. Quoting a popular NGO phrase, many 'outputs' have been produced but few 'outcomes' are yielded.

Books, reports, proceedings are burgeoning but corruption remains endemic and the roots of community conflict remain unresolved.

To be fair, the problem might also lay on the measurement of the outputs and outcomes. People might expect change to occur at the societal level but in reality the program only targets the community level. Further, since the framework of the program is usually multi-years (e.g. three, five years), then the results only appear in the long-term.

It does not make any sense to anticipate bureaucracy apparatuses would transform in months or hoping that communal conflict would be settled in a year.

This should be a problem solved by NGO communities: how, on the one hand, big impacts (e.g. significant reduction of corruption) can be achieved while, on the other hand, the public are kept informed of the small changes (e.g. perception change on corruption).

The second consequence uncovers NGOs as the extension of foreign interest supported by international actors such as the World Bank, the IMF and development agencies like USAID and AUSAID.

Two following effects emerge here: first, bureaucratization of NGOs and, second, paving the way for donor's real interest. The first describes the nature of NGOs that reduce substantial changes into matters of procedures, to do lists and matrices (De Valk, 2010). Moreover, by immersing themselves in bureaucratic works, NGOs have rarely critically questioned what the motives of donors to disburse fund are? Or, why donors prefer one NGO rather than others?

The second goes deeper than only exacerbating bureaucratization of NGO works. As a consequence of a lack of reflection of the interests and agenda of donors, unconsciously, NGOs have been expanding and sustaining the international organization's agenda.

The problem lies within international organization's interests commonly objectified as conditionality. Contained within conditionality is, for instance, the motivation to push market liberalization (Hadiz, 2004) or consolidating US hegemonic roles (Robinson, 1996).

Without critical examination on these agenda, NGO can fall into the trap to sustain international agenda which might not be coherent with the communities' needs it is advocating.

To some extent, the inspection of NGO social ties can help us clarify some popular images circulating in public discourses.

It is important to keep in mind that behind proposals, matrices, trainings and empowerment activities, there are processes which should be taken into account to judge NGO's works.

The writer is alumnus of Institute of Social Studies (ISS), The Hague.