A tale of infamous waterfront houses of ill repute

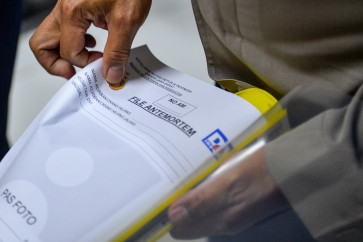

JP/Seto WardhanaIn the days of yore, so legend goes, people named a place after its function

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

JP/Seto Wardhana

In the days of yore, so legend goes, people named a place after its function. So they called this once lush green place where some Jakartans’ lonely ancestors came to find a concubine “Kalijodo”, or “Kali Jodo”, which literally means “river of partners.”

Economic activity in the area dates back to the 1600s when Batavia, which makes up the present day’s downtown Jakarta, was under the administration of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). During this time, thousands of Chinese people fled wars in their homeland and found refuge in the sparsely populated city.

In the 17th century, the ethnic Chinese made up the majority of Batavia’s population, according to a well-documented survey commissioned by Jan Pieterszoon Coen, then governor-general of the Dutch East Indies and founder of Batavia, the capital city of the Dutch colony.

Foklore has it that the Chinese arrived in Batavia without their wives. Well-known for their unwavering bond with their ancestral culture, the migrants made themselves at home by holding traditional water festivals in the vast, slowly flowing river of Angke, which with tongue firmly planted in cheek they then called Kalijodo.

Among the most popular celebrations was the series of Lunar New Year festivals featuring a wide range of cultural attractions such as the signature lion dance (barongsai) and gambang keromong musical sponsored by Chinese tycoons.

As recreational and economic activity was bustling, the river became a popular place where men went to look for female partners — mostly indigenous women — to take the place of the wives they had left behind in China.

Among regular patrons were blue collar workers of the nearby port of Sunda Kelapa.

In his 2001 best-selling novel Cau Bau Kan set in 1930s Batavia, Remy Sylado reconstructs some of the typical romantic rituals of the legendary river. In one scene involving protagonist Tinung, women on board decorated boats try to win the hearts of Chinese men by singing classic Chinese love songs.

Then, the river emptying into the Batavia bay was described as an idyllic, leisurely place. That may be in stark contrast to the present situation when the water stinks most of the year from industrial and domestic waste.

Cau bau, or women in search of men at Kalijodo, were not prostitutes despite the financial transactions involved because they earned the money for the entertainment they rendered rather than sexual favors. “Then there was no criterion to judge if an activity counted as prostitution,” says Remy.

Water revelry was the main attraction for the younger people then. In one attraction, the fun ride, two boats — one carrying four men and the other carrying four women — would sail side by side with the passengers stealing looks at each other. A male rider would throw a cake called Tiong cu pia at a woman he fancied and she would pelt him back with it if she liked him too.

The ritual came to an end in 1958 after then Jakarta mayor Sudiro banned Chinese culture shows in the capital. And, unfortunately, the racist policy was cemented by the staunchly anti-communist strongman Soeharto, who banned all kinds of Chinese symbols in the public sphere.

Despite the loss of the Chinese cultural activity, Kalijodo continued to develop into a virtually untouchable gangland where illegal prostitution and gambling thrived on state property, presumably under the patronage of corrupt individuals in the police, military and government.

For decades, Kalijodo had a reputation as a safe haven for gambling and a home to low-class prostitutes. Brothels were open 24 hours but cafes and karaoke parlors would open only at 8 p.m. and close at dawn. The 1999 closure of Kramat Tunggak, another major red-light district in North Jakarta, turned out to be quite a boon for Kalijodo.

Since the early 2000s, Kalijodo’s romantic image had virtually been lost to gangsterism and occasional turf wars. In 2001, a human trafficking scandal in which young women, some even under aged, were being sold as prostitutes put the gangland in the media’s spotlight.

According to Geger Kalijodo (Wars of Kalijodo), a book authored by former local police chief Sr. Comr. Krishna Murti, the lucrative illegal business was effectively controlled by well-organized ethnic-based gangs: Mandar, Bugis and Banten. Each claimed to have their own army of thugs numbering in the hundreds.

In 2003 and 2010, the government attempted to close it down but to no avail. In his book, Krishna also describes how the dreaded hoodlums of the Mandar gang defeated Islam Defenders Front (FPI) vigilantes who raided the complex in early 2000s.

In light of this, when forcibly evicting Kalijodo inhabitants, the city administration mobilized thousands of police, military and public order officers. However, they met no resistance.

Today, when Jakarta is busy turning the once sleazy place into a public space, there has been a push to reimagine the Chinese cultural festival that made Kalijodo a legend.

All the buildings, the flimsy and permanent alike, have been torn down and the whole strip rebuilt. The future monumental building there may be a two-storey mosque that will soon be built across the strip to change the spot’s sinful image to religious.

Perhaps history enthusiasts who have lost traces of ancient Jakarta romanticism would still be able to imagine Kalidodo’s past grandeur if the Jakarta administration also restyles the colorful (Chinese) cultural events.