Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsRI struggles to define, instil ‘character education’ in 2017

Controversial policies and corrupt practices at universities throughout 2017 have undermined President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s pledge to reform the country’s education system

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

C

ontroversial policies and corrupt practices at universities throughout 2017 have undermined President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s pledge to reform the country’s education system.

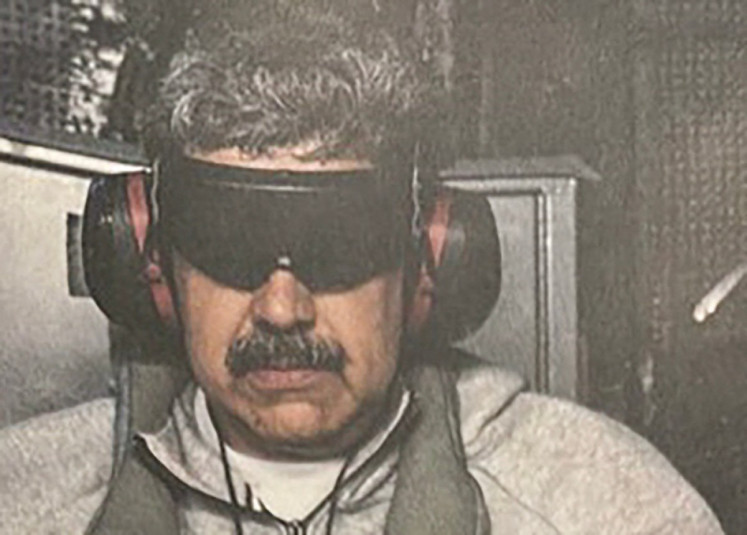

When Muhadjir Effendy, an academic from Islamic Muhammadiyah University in Malang, East Java, was installed as Indonesia’s new culture and education minister replacing now-Jakarta Governor Anies Baswedan in July 2016, he faced the arduous task of bringing Jokowi’s “mental revolution” credo to bear on the school curriculum.

Muhadjir was soon under fire for his full-day school policy, which was intended to instill character education yet opposed by many for obliging students to spend more of their weekdays at school. This year, the initiative again came up as his most onerous challenge.

Muhadjir triggered widespread anger from Islamic grassroot communities with his decision in June to extend the school day to eight hours — albeit in return for Saturdays off. Many, notably Indonesia’s largest Muslim group Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), feared the decision would undermine madrassas across the country, which usually start after school hours.

NU clerics publicly decried the new policy, while Muhammadiyah, Indonesia’s second-largest Muslim group after NU, in which Muhadjir is a member, strongly backed the decision as a means to rejuvenate Indonesia’s education.

The bickering ended when Jokowi issued in September a presidential regulation on character education overriding the previous regulation issued by Muhadjir — in a move reminiscent to what happened in 2016, when Jokowi overrode the minister’s decision to suspend national exams.

The presidential regulation stipulates that character education at schools may be carried out within either a six-day or a five-day school week, while the previous regulation mandated eight hours of school a day in a five-day scheme.

The new regulation accommodates the interests of madrassas by allowing them to decide the school day, along with school authorities.

But the new regulation soon became the object of criticism by education experts, who said it “lacks clarity and detail” on how to implement character values in daily academic activities.

Apart from the controversy over the character education policy, the Jokowi administration this year struggled to issue the Indonesian Smart Card (KIP) to students.

The government has targeted to distribute the KIP, through which children aged 7 to 18 years from poor families can enjoy a stipend amounting to between Rp 400,000 (US$28) and Rp 1 million per year, to 19,927,380 children.

As of November, however, the government has only distributed the cards, which also serve as ATM cards allowing recipients to withdraw cash from their accounts, to 13 million children at various school levels.

Problems have also hampered reforms in higher education, which Jokowi wants to become Indonesia’s backbone in order for the country to benefit from the expected demographic bonus.

The country was flabbergasted by a report over perennial practices of doctoral degree scams at the Jakarta State University (UNJ), one of Indonesia’s most reputable state universities, which led to the resignation of its rector.

UNJ is among four universities identified by the government where doctoral degree scams allegedly took place.

At UNJ, the government has found numerous indications leading to allegation of degree scam, such as plagiarism of dissertations, students concluding their studies faster than usual and a bizarre number of doctors produced in a period of eight months.

The findings come as the government strives to improve the quality of higher education in Indonesia, seeing that 2,279 of more than 4,000 universities in Indonesia have either a C-level accreditation or no accreditation at all.

Meanwhile, this year also saw various attempts by Research, Technology and Higher Education Minister Mohamad Nasir to forge close communication with universities across Indonesia to counter radicalism, which has been considered as a key factor in the division of factions in the country for several months this year following the blasphemy case implicating former Jakarta governor Basuki “Ahok” Tjahaja Purnama.