Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsRevising history: A return to an incomplete narrative?

The rewriting of national history is a calculated move to bolster an increasingly authoritarian government, as it relies solely on scholars and historians with ties to those in power.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he government’s plan to rewrite its official national history was initially met with positive responses, particularly for its goal of better serving the younger generations. But the project to reshape the country’s mainstream historical narrative soon ignited widespread controversy for obfuscating histories of oppression and reinforcing authoritarian tendencies.

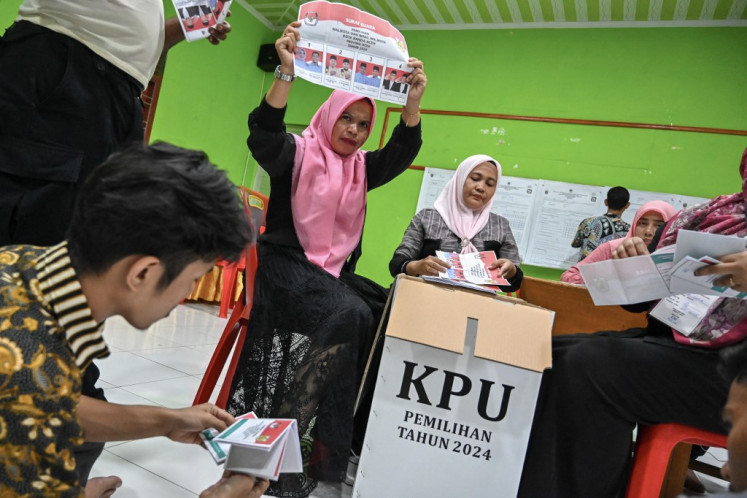

By incorporating the latest data and expanding coverage of historical events and figures, the initiative, launched by the Indonesian Historian Association (MSI) and backed by the Culture Ministry in May 2025, raised hopes for a more inclusive, accurate and relevant national history.

However, backlash soon followed, with criticism intensifying after Culture Minister Fadli Zon’s controversial statement dismissing the 1998 mass rapes as mere rumors.

Various groups argue that the rewriting of national history is a calculated move to bolster an increasingly authoritarian government, as it relies solely on scholars and historians with ties to those in power.

A nation’s relationship with its history is deeply tied to the way in which contemporary narratives are constructed or shaped. For national historiography to carry legitimacy, it must meaningfully include the voices of diverse groups, classes, communities and entities.

However, the project’s terms of reference fail to give due attention to space for women’s roles in the Indonesian independence movement.

Its treatment of historical narratives from regions beyond Java also remains insufficient, and so does its neglect of non-political and non-economic themes, such as the arts or sports.

In response to the controversy, few formal statements have been made from either the MSI or the historians involved in the project, apart from the minister and the project’s principal editor.

One notable exception came from a historian via his social media page, where he reflected on the dilemma of being both an intellectual and a public servant involved in the project.

He argued that speaking from within, rather than criticizing from the outside, demands greater courage and careful calculation, a stance he fears is likely to be overlooked.

As a history-and-culture researcher, his remarks reinforce the perception that many of the historians involved in the revision project are civil servants at state universities or individuals closely aligned with those in power.

History itself tells us that the writing of national history is deeply intertwined with the interests of ruling authorities and their affiliated groups.

From its inception, the genre of national history that emerged in 19th-century Europe and the United States was closely tied to efforts to legitimize territorial expansion and colonial rule.

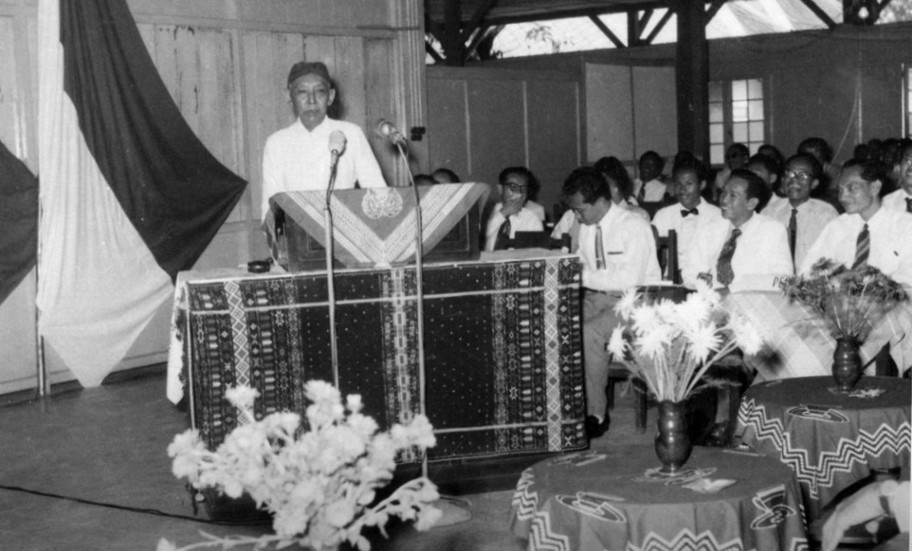

In the context of Indonesia’s current national history revision project, it is worth revisiting comparisons between how national histories were written under Ferdinand Marcos in the Philippines and Soeharto in Indonesia.

Historians in both countries should be recognized as active agents with their own interests and authority, not as passive participants or easily influenced figures.

During Soeharto’s regime, one historian even withdrew from the state-led national history writing project due to disagreements, particularly over methodological approaches.

The project’s director marginalized historian Sartono Kartodirdjo, who championed a multidimensional approach, in favor of a more linear, state-centric narrative. Sartono’s more holistic perspective made space for a broader range of historical actors, including farmers and other often-overlooked communities.

A similar precedent can be traced back to the early years of Indonesian independence, when the government initiated efforts to document the country’s national history in the 1950s. At the time, the National History Writing Committee, comprising prominent scholars, organized Indonesia’s first National History Seminar.

Yet the initiative failed to produce an official national history, partly due to the same kind of unresolved methodological debates that resurfaced during Suharto’s rule.

Marcus Tullius Cicero, the Roman philosopher-turned-statesman, once said, historia magistra vitae est: history is the teacher of life.

Given the failures and controversies surrounding Indonesia’s earlier attempt to produce an official national history, the current revision project demands critical re-evaluation, and, if necessary, a complete halt.

Merely involving more historians to boost representation is not an adequate solution either.

The core issue lies not in revising history, but in advancing Indonesian historiography. Rather than pushing ahead with an extensive national history rewrite, the government should prioritize fostering diverse local history initiatives, through programs such as the Cultural Endowment Fund or the Indonesiana Fund.

This approach would enable a more comprehensive and representative account of Indonesian history, one that integrates local perspectives while remaining connected to national and global narratives.

---

The writer is a post-doctoral researcher at the Royal Netherlands Institute of Southeast Asian and Caribbean Studies. The article is republished under a Creative Commons license.