Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe national hero title for Soeharto: A monument to impunity

The granting of the hero title to Soeharto represents a denial, if not an outright betrayal, of the Reform movement, which was initiated in 1998 to end his corrupt dictatorship.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

O

n the occasion of this year's Heroes' Day on Nov. 10, President Prabowo Subianto designated New Order founder Soeharto as a national hero. Supporters of this decision portray Soeharto as central to establishing the foundational strategies for national development, highlighting a period during which economic growth reached levels as high as 8 percent, an achievement unmatched by any post-Soeharto president.

Additionally, he is credited with maintaining stability, which facilitated ongoing development, extending to social and political dimensions as well.

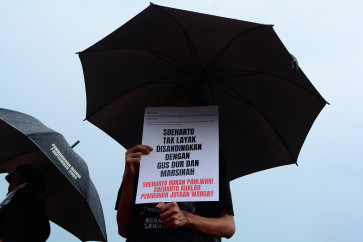

The Council for the Award of Decorations and Honors, chaired by Culture Minister Fadli Zon, known for his admiration of Soeharto, also proposed nine other figures as recipients of the national hero title this year, including former president Abdurrahman “Gus Dur” Wahid, labor activist Marsinah, and former foreign minister Mochtar Kusumaatmadja. Strangely, Gus Dur and Marsinah were known for their fight against Soeharto’s regime.

The selection of Soeharto as a national hero undoubtedly opens up a debate, as it distorts the public logic surrounding the birth of the 1998 Reform movement. The granting of this title not only represents a denial, if not an outright betrayal, of the Reform movement, but also serves as a perfect form of impunity for this authoritarian ruler for the widespread human rights abuses and the corruption, collusion and nepotism (KKN) that marked his 32 years in power.

History records that Soeharto's resignation on May 21, 1998, was precipitated by a debilitating financial crisis that began in mid-1997. This crisis unmasked the rampant, institutionalized KKN that permeated his regime, simultaneously exposing the fragility of the economic foundations constructed by the New Order. National wealth was concentrated in the hands of a few power brokers (oligarchs), while ordinary citizens faced hardship. Furthermore, development was heavily centralized in Java, neglecting other regions.

If the economic foundation established by Soeharto were indeed solid and free from KKN, there would have been no need for People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) Decree X/1998 on the principles of development and reform. Similarly, the spirit of Reform birthed MPR Decree XI/1998 on governance clean and free from corruption, collusion and nepotism (KKN). Article 4 of this decree mandated that the eradication of KKN had to be rigorously applied to everyone, regardless of their position, including the late president Soeharto.

Although the MPR removed the specific reference to the deceased Soeharto from Decree XI/1998 last September, the spirit and principles of KKN eradication remain foundational for subsequent legislative measures, such as Law No. 31/1999 on corruption and Law No. 30/2002 on the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK).