Contesting ‘true Islam’ in contemporary Indonesia

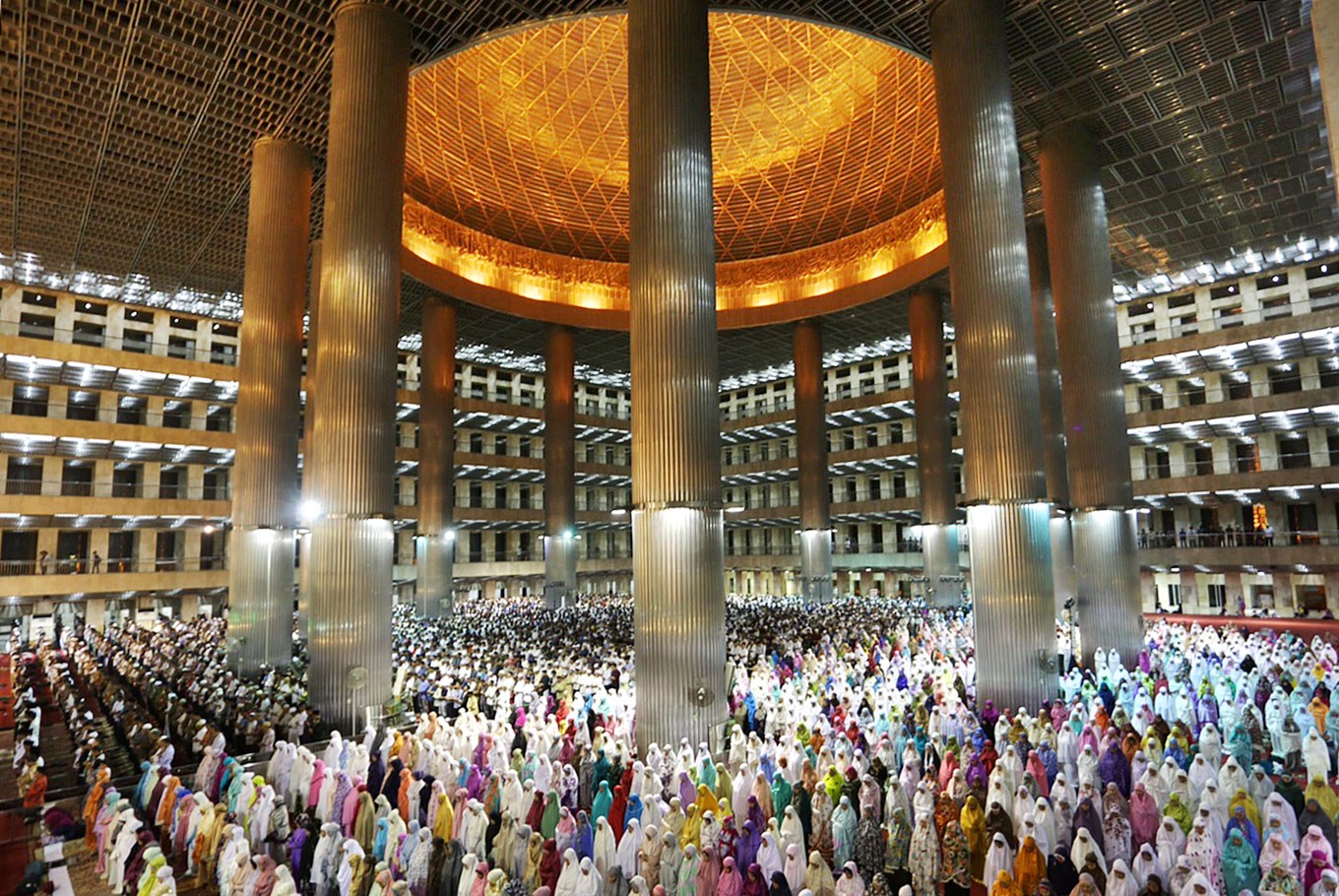

Further, some Indonesian Muslims are currently fighting for an imagined, single brotherhood of Muslims, which not only aims to be a sanctuary but is also seeking a new unifying figure.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

H

istorically, Islam and Indonesia have been two areas of contention since the nation declared independence 75 years ago. Long before that, the births of the two largest Islamic organizations in Indonesia, namely Muhammadiyah (1912) and Nahdlatul Ulama (1926), were inseparable from the national independence spirit that fought for freedom from the shackles of colonialism.

Notwithstanding the national ideals agreed in the Pancasila (five pillars) as the state ideology that unified the plurality spanning the archipelago from west to east, living together amidst diversity remains a challenge for religious life in Indonesia, especially after 1998.

Some scholars have said that post-authoritarian Indonesian Islam has colored Islam with conservatism (van Bruinessen, 2013). The increasing strength of religious identity politics is but one interpretation of the religion, which at least contains the call to command right teachings and forbid wrong teachings, as well as the promise of happiness in life after death.

This interpretation arises from many factors, such as how justice has not turned out to be as imagined. This has prompted harsh criticisms of liberal democracy, neoliberalism and globalization, as well as the nation-state. For some Muslims, the ideals that were built from these discourses have never been proven, so they have boldly offered Islamic law enforcement as a counter discourse.

Further, some Indonesian Muslims are currently fighting for an imagined, single brotherhood of Muslims, which not only aims to be a sanctuary but is also seeking a new unifying figure.

Therefore, Islamic populism has grown in strength because it is understood to be an effort to raise the voice of Muslims who have marginalized by the elite. The narrative that has developed is of Muslims who have experienced oppression, including a sense of being marginalized by other forces or groups. In this, we must also remember that the media exaggerate the news and polarize society.

What is certain is that the inferiority complex of some contemporary Indonesian Muslim communities points to a serious problem and is a challenge in itself. For instance, the attitudes towards different groups, and not just different religions but much more crucially, different beliefs within the Muslim community, indicate that there is a struggle over “true Islam” and its various interpretations, which of course cannot be prevented.

From a slightly different angle, past scholars have written about this situation, that the Islamic world is currently experiencing a predicament, a kind of crisis or instability. One of the indications of this is the "sense" of confrontation towards the West.

It is a "sense" because this confrontation does not really exist. What exist are perceptions as a result of historical experiences, such as the oft-repeated rhetoric of crusade and colonialism. Thus, these perceptions settle in the Muslim consciousness or subconscious, giving rise to symptoms that seem anti-Western (Madjid, 2005).

Reading the reality of contemporary Indonesian Islam, of course, cannot be separated from reading how Indonesia was founded as a country of various ethnic groups that were ethnoreligious-centric in nature, before it transformed into a nation-state.

Ethnoreligious centrism is understood as the Assabiyah concept introduced by Ibn Khaldun, or what Durkheim referred to as a traditional society with mechanical solidarity that is homogeneous, charismatic, communal and seemingly exclusive, so the transformation towards a nation-state requires the existence of citizen ethics in building a moderate, egalitarian, equal and fair public space.

Besides that, a multicultural and plural nation-state also requires moderation of religion, culture, ethnicity, gender and other aspects in social relationships and interactions.

There is a struggle over Indonesia as an unfinished project in being and becoming a nation-state, such as in how the interpretations of Pancasila have continued until recently, by understanding ethnoreligious communality as mono-existence.

Coexistence, in contrast, avoids inclusivity, as seen during the New Order era. Religious life was strict, did not interact and maintained a monoculture that relied on the rhetoric of the religious elite, upheld prejudices and possessed a potential to ignite conflict over certain issues.

What might be offered is a kind of pro-existence, namely an engaged inclusivity based on civil initiatives towards mutual support (Dzuhayatin, 2020), in which the values of ethnoreligious communality contest citizen ethics.

Thus, it appears that the phenomenon of urban populism is different from ethnoreligious communality in terms of their interests. Urban populism tends to be short-term, both economic and political, with fanaticism as its center, and tends to be exclusive and intolerant. There are shared interests and shared benefits. On the other hand, an ethnoreligious community refers to sustainability and charismatic elements as the basis for developing society.

However, in contemporary Indonesian society, urban religious populism needs to be addressed because it has the potential to threaten the national ideals.

Lastly, the dialectic of religion (Islam) and the nation-state (Indonesia and democracy) is still needed so that, to use a metaphor, hell does not occur on earth. On the other hand, we also need to remember that the idea of the nation-state also contains the potential for state violence through acts of exclusion and inclusion amidst diversity.

However, as a religion-friendly state where moderation has become habitus, Indonesia has long adopted the Islamic paradigm of the ummah wasat (middle path), which in the political arena has been translated as the adoption of the Pancasila state ideology (Azra, 2017). Thus, the contestation of "true Islam" should be seen as an open and dynamic Indonesian religious asset, especially over the last 20 years.

***

The writer is a doctoral student at the Institute of Anthropology, Heidelberg University, and member of Muhammadiyah special branch of Germany.