'Robert Johnson' of Indonesia's Orkes Melayu music finally comes out from the shadows

After months of woodshedding, the band gathered enough materials that they would use to join a recording session at Irama Records studio in Menteng, Central Jakarta, supervised and engineered directly by founder of the legendary label, Suyoso "Mas Yos" Karsono.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

n the early 1960s, two of the best talents in the Indonesian music scene, songwriter and band leader Adi Karso, known for his hits "Papaya Cha-Cha-Cha" and "Balonku" and Gambus musician Munif Bahasuan, the son of a rich businessman from Tanah Abang, Jakarta, teamed up to form Orkes Melayu (Malay Orchestra) Kelana Ria.

After months of woodshedding, the band gathered enough materials that they would use to join a recording session at Irama Records studio in Menteng, Central Jakarta, supervised and engineered directly by founder of the legendary label, Suyoso "Mas Yos" Karsono.

Between 1961 and 1964, Kelana Ria recorded 48 songs that were spread over four records, Kafilah, Yam El Shamah, Ya Mahmud and Ya Hamidah.

The four recordings changed the trajectory of Indonesian popular music.

Songs like "Termenung, " written and performed by Ellya Khadam became an instant hit and were staples on the playlist of state-run broadcaster RRI. Many deem "Termenung" as the first proper Orkes Melayu hit.

Another song, "Ratapan Anak Tiri," became so popular that a film producer decided to make a movie based on its lyrics. The film became a blockbuster in the early 1970s.

The album also turned Munif – who composed and sung a number of songs on the four records, including two with Arabic lyrics – into a superstar and his name will forever be associated with the mix of Arabic, Indian and Latin music that Kelana Ria popularized.

Munif went on to record more albums in those styles and achieved greater mainstream success in the 1970s.

Another key figure in Indonesian music born out of the four Kelana Ria recordings was Juhana Sattar, whose soulful and mesmerizing vocals in songs like "Pujaanku" (My Darling) and "Ditinggal Pergi" (Left Behind) catapulted her to an Etta James-level of popularity in Indonesia.

Aside from launching the careers of performers who would become the giants of Indonesian pop music, the four recordings also introduced to the country some of the most memorable and most popular songs, so popular that people in present-day Indonesia often mistake them for traditional folk songs, born decades ago in the milieu of the Malay culture.

Beyond borders

Play "Renungkanlah" (Think About It), the first composition that opens Side B of Yam El Shamah, a love song with heavenly melodies and lilting harmonies, to an audience in the Western part of Malaysia or people of Malay ethnicity in Singapore and they would immediately hum along the tune.

"Renungkanlah" has been covered by many countless other musicians in Indonesia and Malaysia and it has become a hit many times over. The song has become a go-to song in karaoke bars in the region, with fans oblivious to who actually wrote this song or who performed it the first time.

Or take the song "Ratapan Anak Tiri" (Lament of a Stepchild), a song that has traversed national boundaries and has become a universal sad song in the Malay world, turning into a shorthand for melancholia that permeates this archipelago of nations.

Another masterpiece from Yam El Shamah is the melancholia-laden "Kesunyian Jiwa" (Silence of the Soul), an operatic tune so majestic that it could open any black and white Kurosawa film from the late 1940s.

"Kesunyian Jiwa" opens with marching percussion and what could pass for a horn section foregrounding an opera finale before settling into a Latin-inspired composition backing one of the most soulful vocal performances from the 1960s.

The songs and the soulful vocal performance belong to Muhamad Mashabi, who despite the popularity of the songs he created is now largely forgotten, whose history was kept alive only in the neighborhood where he grew up, in Kebon Kacang, Central Jakarta.

There is no official record of when he was born and there is even more confusion as to when he passed away. Some initially believed he passed away when he was 27, joining the ranks of other music idols who also died young the likes of Kurt Cobain, Janis Joplin and Robert Johnson.

The Robert Johnson comparison seems apt given that there was so little that was known about the African-American blues musicians before he was found by music archivists who reintroduced him in the 1960s and started the whole rock and roll revolution.

Mashabi, like Johnson, left a dearth of photographic evidence from his time in the world. Until very recently the only visual aid to prove Mashabi's existence was a solitary black-and-white photograph kept by his siblings.

Mashabi's premature death has also inspired some tales, not too dissimilar to that of Johnson, that due to his immense talent and charisma, he fell victim to a kind of witchcraft performed by some people who were jealous of his success.

Melancholic soul

For the four siblings, who continued to live in Mashabi's family home, built in the 1930s on a small plot next to what used to be Arab cemetery in Kebon Kacang, the late singer, known in the family as Mamat, was an embodiment of the sadness and melancholia that became the motifs of his songs.

"The song 'Ratapan Anak Tiri' was written after his trip to Lampung when he saw a kid crying by the road and found out that he was abused by his stepmother. Anything he wrote in the lyrics was based on his conversation with the boy, " Mashabi's younger brother Abu Bakar told The Jakarta Post in a recent interview.

As for his most majestic song “Kesunyian Jiwa", the composition was the outpouring of Mashabi's feeling of being denied of happiness resulting from a failed romance.

"He was so deeply in love with this syarifah [girl from higher caste group] who was forbidden from marrying someone from a lower class upbringing," Abu Bakar said. Mashabi’s family was from an Arab ethnic group who could trace their origin to Hadramaut, the present-day Republic of Yemen.

In regard to Mashabi's death, Abu Bakar is convinced that it was the result of a plot to end Mashabi's performing career.

"This is the first time I divulged the subject [...] he showed no illness before his death," Abu Bakar said, adding that Mashabi was 37 when he passed away.

With only a short musical career and only nine recorded songs from almost 40 compositions, Mashabi fell by the wayside in the early 1970s, especially with the rise of pop and rock from bands like Koes Plus, Panbers and God Bless.

Yet his songs, inspired by Malay traditional songs but performed in the modern studio setting, lay the foundations for what would become the biggest musical genre in the country, dangdut, especially the kind that was popularized by the self-styled king of the genre, Rhoma Irama.

"Mashabi's distinctive vocal style and soul-searching lyrics helped give rise to dangdut, Indonesia's most popular music genre," University of Pittsburgh music professor Andrew N. Weintraub said. Weintraub wrote the liner notes for an upcoming compilation of Mashabi's music released by an independent Jakarta-based label.

Fellow musician Munif, in an interview for the BBC in 2016, said Mashabi was a true originator.

"I don't think there's a dangdut singer who can express feelings like him. He always sings from the heart," Munif said.

Some of Mashabi's music found a new audience in the 1980s with some of his original compositions being reissued in numerous cassette tape compilations.

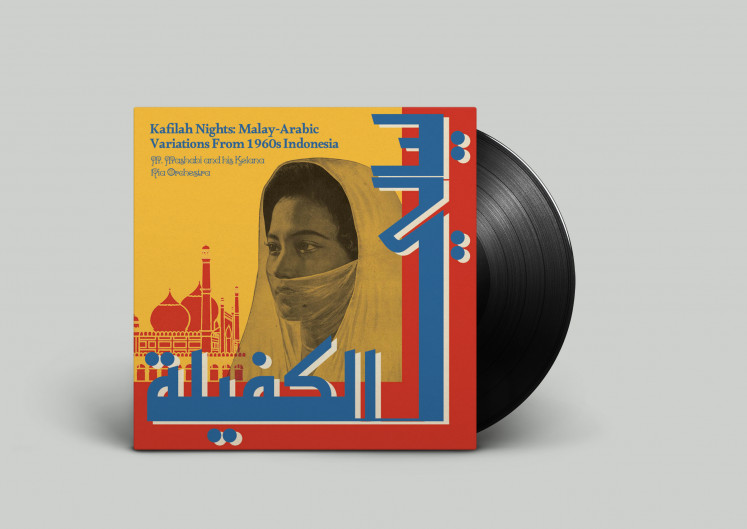

The latest compilation project, titled Kafilah Nights: Malay-Arabic Variations from 1960s Indonesia, which will also be released worldwide, will be a more ambitious initiative taken to reintroduce Mashabi to a younger and wider audience.

The vinyl compilation will be the latest move to pay tribute to Mashabi.

In 2021, the Jakarta administration named a stretch of road in Kebon Kacang, leading up to the Hotel Indonesia traffic circle Jl. M. Mashabi in honor of the singer.

Later in August, Indonesian state-owned post office Pos Indonesia will release a stamp bearing Mashabi's only photo.

"I know that he will finally get recognition. He wrote the best songs," Abu Bakar said.