Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsASEAN must facilitate Myanmar’s return to democracy

The Tatmadaw should be encouraged to release Suu Kyi, politicians, activists, journalists, students and others who have been arbitrarily detained, and take practical and conciliatory steps forward.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

O

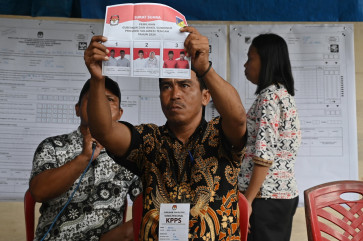

n Feb. 1, the world was stunned as the Myanmar military, known as the Tatmadaw, seized power on the day of the convening of the newly elected parliament after the nation voted decisively for the return of Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy in the November 2020 election.

In one swift coup d’etat, the Tatmadaw has dealt a devastating blow to Myanmar’s decade-long experiment with political, social and economic liberalization and returned Myanmar to the military rule that it has known for far longer.

As the commander in chief, senior general Min Aung Hlaing, leads a military government under a state of emergency and faces international condemnation, isolation and calls for punitive sanctions, how will ASEAN, of which Myanmar is a member, respond?

The limitations of ASEAN are well documented, with the principles of non-interference and consensus decision-making restricting its ability to act. But there are also elements of trust, understanding and goodwill within the regional grouping, which the rest of the international community lacks when it comes to Myanmar. ASEAN has the advantage of being willing and able to directly engage with its member states when others cannot.

There is great political diversity among the ASEAN member states, and Myanmar is not the only nation in the region to have experienced military coups. So it is perhaps unsurprising that the responses from member countries have varied.

Malaysia, Indonesia, and Singapore have expressed grave concern and called for a peaceful resolution. Others, such as Cambodia and Thailand, initially referred to the coup as a domestic matter to be resolved by Myanmar, although the prime minister of Thailand also highlighted the importance of ASEAN taking a collective stand.

A statement from Brunei as the Chair of ASEAN recalled the principles of the ASEAN Charter, including the adherence to the principles of democracy, the rule of law and good governance, and respect for and the protection of human rights.

ASEAN needs to speak with a collective voice and sense of unity to have any chance of positively influencing events in Myanmar as the repercussions and destabilizing effects of Tatmadaw rule will be felt across the whole region. Although we should be realistic about its leverage, ASEAN also needs to seriously consider that failing to act in this crisis will likely diminish its international standing.

If it wants to cultivate the image of a regional force that prioritizes peace, stability and prosperity, and is truly committed to the principles in the ASEAN Charter, now is the time to step up.

The days and weeks since the coup have prompted outrage within Myanmar, with tens of thousands of people taking to the streets daily, protesting across the country. With the military unlikely to give in, and in light of historic precedent, there is good reason to fear that this could end with a violent crackdown against protestors.

There will be particular alarm among the already persecuted ethnic minorities in Myanmar. These ethnic communities in Shan, Kachin, Kayin, Mon and Rakhine states have suffered atrocities for decades, leading to allegations of crimes against humanity, war crimes and even a case of genocide against Myanmar at the International Court of Justice for its persecution of the Rohingya. Despite the disappointing performance of Suu Kyi’s government in this regard, there is fear that life under military rule will be even worse for ethnic minorities.

While there is a sense that ASEAN cannot do much when a member state is determined to ride out the storm, given the lackluster response to Myanmar’s “clearance operations” against the Rohingya in 2017, there is a significant precedent to show that ASEAN can engage effectively with Myanmar in times of great difficulty.

When Cyclone Nargis struck Myanmar in 2008, the military government initially refused much needed international aid, and the natural disaster turned into a major humanitarian crisis, and a standoff between the military government and the international community ensued.

However, the regional grouping was able to negotiate with the military leaders, bringing about an unprecedented breakthrough, with ASEAN leading a tripartite humanitarian mechanism along with the Myanmar government and the United Nations. This demonstrates that ASEAN is capable of working productively with military leaders for the greater good of the whole population, and of acting as a mediator between them and the international community.

ASEAN must endeavor to use its unique position and relationship with Myanmar to project a positive influence on the military government. For a start, rather than waiting for the next scheduled meeting in the calendar, a special ministerial meeting as called for by the prime minister of Malaysia and the president of Indonesia should be convened to urgently decide upon a more proactive and unified response.

The Tatmadaw should be encouraged to release Suu Kyi, politicians, activists, journalists, students and others who have been arbitrarily detained, and take practical and conciliatory steps forward. To do so, the Tatmadaw must adhere to the wishes of the Myanmar people and respect their rights to speak out, protest peacefully, and be governed by the representatives they elected. It should also lift all internet, telecommunications and social media restrictions and ensure access to information.

While the international community grapples with how best to respond, it is likely that greater sanctions will be imposed, targeting individuals and entities, banning investment and trade, and suspending development aid and technical assistance. This will clearly not serve the interests of the Myanmar population, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic when international cooperation, aid and support are crucial.

Myanmar’s road to democracy has been long and arduous and it must not be allowed to stop here. A peaceful solution must be reached in the best interests of the country’s whole population, including all ethnic minorities.

ASEAN has a chance to be a part of that solution and should make the most of this opportunity to facilitate constructive dialogue, reconciliation and the return to democratic governance in line with the will of the Myanmar people.

***

The writer is the representative of Malaysia to the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights (AICHR)