Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsVaccines save lives

The big announcement about the vaccine being haram has likely given vaccine skeptics enough reason not to take the government-sponsored jabs.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

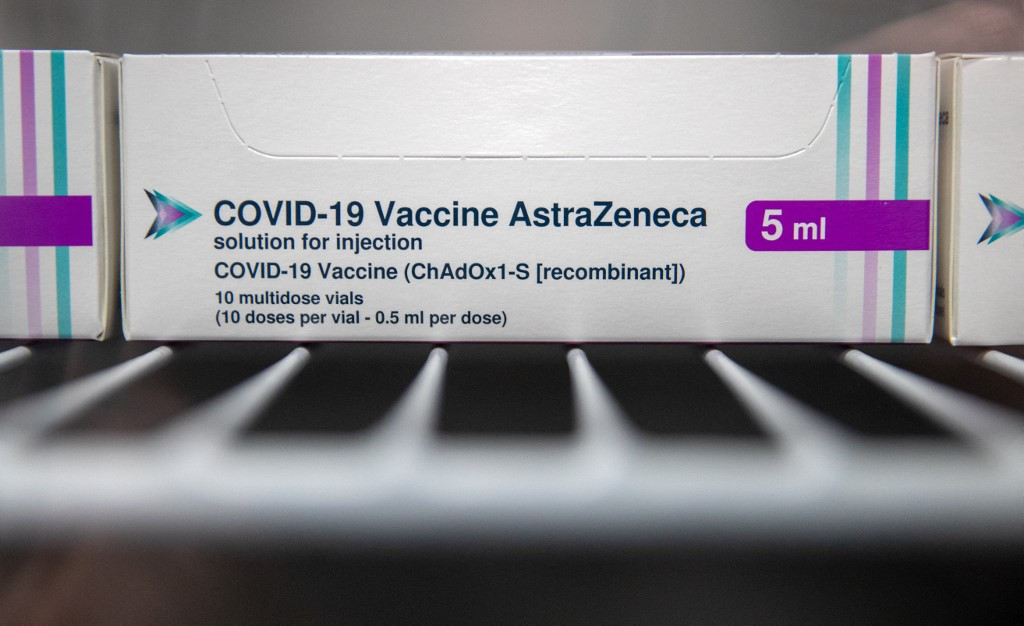

Boxes of vials of the Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine are seen on Jan. 9 in a refrigerator at Ashton Gate Stadium in Bristol, England, one of seven mass vaccination centers that are set to open next week as Britain continues its vaccination program against the pandemic. (Agence France Presse/Andrew Matthews)

Boxes of vials of the Oxford AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine are seen on Jan. 9 in a refrigerator at Ashton Gate Stadium in Bristol, England, one of seven mass vaccination centers that are set to open next week as Britain continues its vaccination program against the pandemic. (Agence France Presse/Andrew Matthews)

E

ven during the best of times, when no public health emergency is in progress, and in the best of places where health infrastructures are readily available, vaccinations are getting more difficult to administer.

Antivaxxers and conspiracy theorists are running rampant at town halls and on social media, sowing doubts about the miracle of this modern medicine. These antivaxxers have made unsubstantiated claims that vaccines could be linked to autism or outrageously moronic allegations that Bill Gates designed computer chips that could go with any vaccine and be used to spy on us.

Now we’re in a once-in-a-century pandemic, and with mass vaccination being the only way out of this public health crisis, it certainly does not help that the country’s highest Muslim clerical council, the Indonesia Ulema Council (MUI), has claimed that one of the vaccines used by the government violated Islamic law.

Late last week, the MUI announced that the AstraZeneca vaccine was haram because the manufacturing process uses “trypsin extracted from a pig’s pancreas”. According to Islamic law, Muslims are banned from even touching pork, let alone consume the animal product.

In response, AstraZeneca defended its product saying that “at all stages of the production process, this virus vector vaccine does not use nor come in contact with pork-derived products or other animal products”.

In the end, the MUI allowed Muslims in the country to take the vaccine, despite it not being kosher, given that the COVID-19 emergency needed the government to take quick action. Yet the big announcement about the vaccine being haram has likely given vaccine skeptics enough reason not to take the government-sponsored jabs.

We can certainly ask why a vaccination program, which should only rely on science for its planning and implementation, should take into consideration any input or fatwa from what should be a strictly religious institution?

The government certainly takes religion seriously when assigning the MUI to decide if our drugs and food are safe for consumption on religious grounds. But religious institutions like the MUI should only play an advisory role and should not have the final say on whether consumers should take certain drugs and not others.

So far, the MUI has given the go-ahead for China’s Sinovac vaccine, CoronaVac, and a half-hearted nod to AstraZeneca. The government is working to secure vaccines manufactured by companies like Pfizer and Moderna. These, too, will have to go through the MUI.

During a pandemic, when swift action is needed to stop the spread of the disease, adding another layer of bureaucracy is not the best idea.

When asked to comment about the MUI’s decision to declare the AstraZeneca vaccine haram, Food and Drugs Monitoring Agency (BPOM) chief Penny Lukito said: “This country doesn’t belong to one group. A decision has been made and we should stick to it.”

As the highest authority to decide the safety of our food and drugs, the BPOM certainly has every right to brush aside the MUI’s comment. After all, “render unto Caesar the things which are Caesar’s”.