Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsAll the things we've lost in translation

Language is a fickle thing, and oftentimes words betray meaning.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

O

ne moment you’re sitting on a couch somewhere in Jakarta, listening to the soft hum of the air conditioner. The next, you’re in Saigon, making your way through a street in war-torn 1960s Vietnam. Or perhaps, watching the sun rise and fall through a small window from a prison somewhere in the French-colonized Algeria.

Stories have the ability to take us to places that we have never been, to see sights that we have never seen; an access to the foreign and strange and familiar, however brief and fleeting.

Ultimately, literature tells us about how people lived. It tells us about what people have cried about, what they have lost. How people wake up in the morning and make their coffee, and how the moon looks before they fall asleep. It tells us about how things fall apart, and how people fall in love. It may even remind us of emotions that we too have felt; whether it be something that we vaguely remember feeling at some time and some place, or something that comes to us with such an intensity that it washes over us and consumes us.

Read also: Books to read when you miss 'Harry Potter'

But language is a fickle thing, and oftentimes words betray meaning. It’s even more difficult when you’re reading works in translation, where it’s easy for meaning to get lost in the chaos altogether. I recall a time when I was younger, assigned to read an Indonesian translation of Hemingway's The Snows of Kilimanjaro. Having been raised abroad, I struggled with the language, and these words in Indonesian felt foreign to me.

In my difficulties to comprehend, I picked up the story in its original English, desperate for some understanding. This was where I had my first encounter with literature being lost in translation. The short story in its original English spoke of a waterbuck, a creature that did not make an appearance in the Indonesian translation. Confused, I traced through each line, carefully paying attention to each word, until finally, I had found something: bebek air, a water duck.

And yet, these kinds of mistakes are not truly what is lost in translation. While unfortunate, this was just a small, careless mistake. The heartbreaking realization of all the things we may have lost in translation came years later, through a reading of Albert Camus’ L’Étranger in its English translation. In an article for The New Yorker, Ryan Bloom dissects the infamous opening line by the eponymous narrator, “Aujourd’hui, maman est morte.” It’s a short sentence, simple almost. For years, many translators in many versions of the novel have used the same opening line: “Mother died today.” Simple, but incorrect. Bloom explains that within the novel’s first sentence, these seemingly minor translation decisions have the power to change the way that readers read and perceive everything that follows.

“There is little warmth, little bond or closeness or love in ‘Mother,’ which is a static, archetypal term, not the sort of thing we use for a living, breathing being with whom we have close relations. To do so would be like calling the family dog ‘Dog’ or a husband ‘Husband.’ The word forces us to see Meursault [the main character] as distant from the woman who bore him […] We condemn or set him free based not on the crime he commits but on our assessment of him as a person. Does he love his mother? Or is he cold toward her, uncaring, even?” Bloom writes in his article.

It wasn’t until 1988 that a translator changed a single word, altering the line to “Maman died today.” Keeping the French two-syllable word maman suggests a touch of softness and warmth that allows the translator to better avoid changing the intended characterization and influencing the reader, he explains.

Read also: ASEAN Literary Festival highlights freedom of expression, inclusiveness

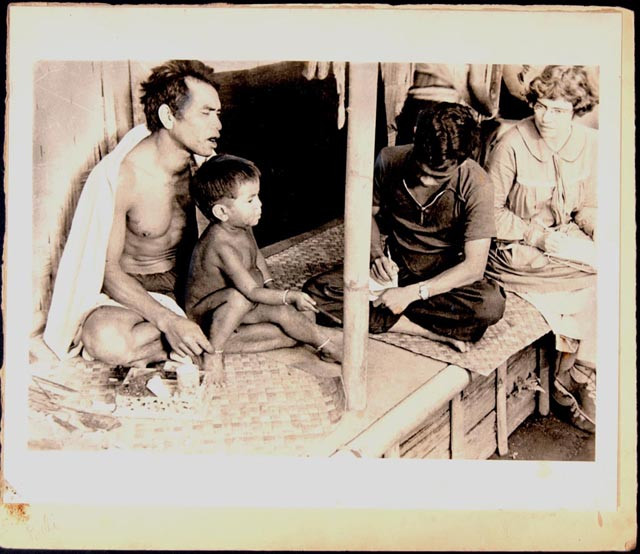

Many consider translation to be an easy task, that any bilingual writer will have the ability to bring a literary piece to life in another language. However, literary translation shouldn’t be done word for word, and translators are not merely invisible and passive mediums through which poetry and prose may pass from one language to the other. There’s an art to translation, the awareness and caution of literary devices and context; an active exploration of the author’s mind and the world around them, as well as their intentions. These are things that many Indonesian publishers do not seem to understand, or if they do, do not seem to care for.

Despite these reservations, I continue to read and explore Indonesian literature. I fell in love with Eka Kurniawan’s dark humor, his refreshingly blunt take on Indonesia’s past; a past that I would have never known or come to understand had his work, Beauty is a Wound, not been translated into English with such thought and concern. My heart ached with Sapardi Djoko Damono’s simplicity, and the way that his poem, “I Want”, had the ability to convey in written words these emotions that I had found so familiar.

Through these translated works, I found myself rediscovering a nation and a place that I have called home for so long, but have never quite understood. While there hasn’t been nearly enough, there are some beautifully translated Indonesian works that translators have crafted with thought and care. I’d like to think that they are now being slowly passed along from country to country, from hand to hand.

It pains me to know that I have fallen in love with words, without ever knowing what the writer had meant to say in their original tongue. But maybe that’s okay. Maybe this gap in knowledge and understanding is a price that we have to pay to be able to get a small taste of what life is like beyond what we already know. And perhaps, that is how things are meant to be, as long as in our translations, we keep trying our best to preserve meaning, so that these messages and wisdom can be passed down to the next generation of thinkers and poets and lovers, and the next.

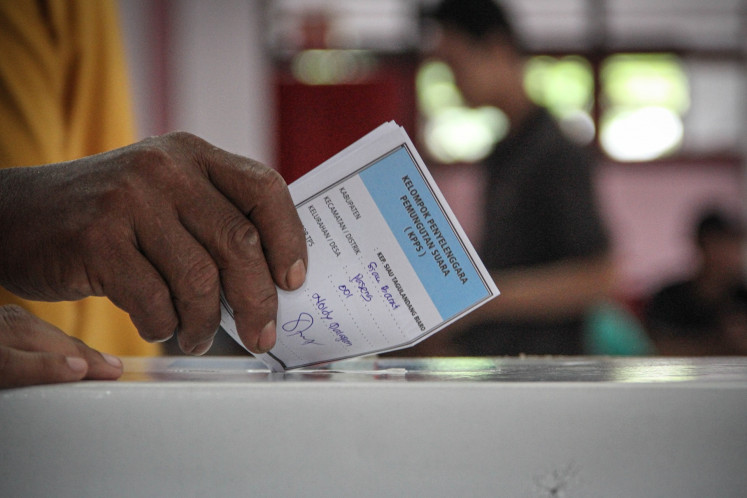

One day, I’ll be able to pick up a book in a bookstore somewhere in New York, or Shanghai, or Buenos Aires and read about how Indonesians lived. I’ll read about what Indonesians have cried about, what they have lost. How Indonesians wake up in the morning and make their coffee, and how the moon looks to them before they fall asleep. I will read about how things fell apart there, and how the people there have fallen in love. It may even remind me of emotions that I have felt; whether it be something that I vaguely remember feeling at some time and some place, or something that comes to me with such an intensity that it washes over me and consumes me.

And one day, someone from a foreign country somewhere will come to discover these things too; and I hope that they too will fall in love with Indonesia. (kes)

***

Currently studying in New York, Christhalia Wiloto enjoys watching the skyline flicker at night and getting lost in art galleries. A writer and artist, you can find more of her work on christhalia.wordpress.com, or see what she’s up to on Instagram, @christhaliaa.

---------------

Interested in writing for thejakartapost.com? We are looking for information and opinions from experts in a variety of fields or others with appropriate writing skills. The content must be original on the following topics: lifestyle ( beauty, fashion, food ), entertainment, science & technology, health, parenting, social media, and sports. Send your piece to community@jakpost.com. Click here for more information.