Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search results‘The Red Ribbon’: A refugee’s search for love and peace

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

Hazara-Afghani refugee has published a poetry collection to tell of his journey from a war-torn country to Indonesia, where he has finally embraced a love of humanity.

“I only pray to see my parents and my siblings once more; dreaming of a peaceful and free world where children like my little brother and sisters don't have to grow up under a chemical sky; a world where women like my mother would never have to cry,” wrote Abdul Samad Haidari in his poem titled “The Pride of a Hazara Child”.

Haidari is a Hazara-Afghani former journalist and poet who has lived as a stateless refugee in Indonesia since 2014.

The poetry, which describes his experience as a child laborer at the age of 10 at a construction site in Iran, is featured in The Red Ribbon, a poetry book he released on Feb. 23 at Goethe-Institut in Central Jakarta.

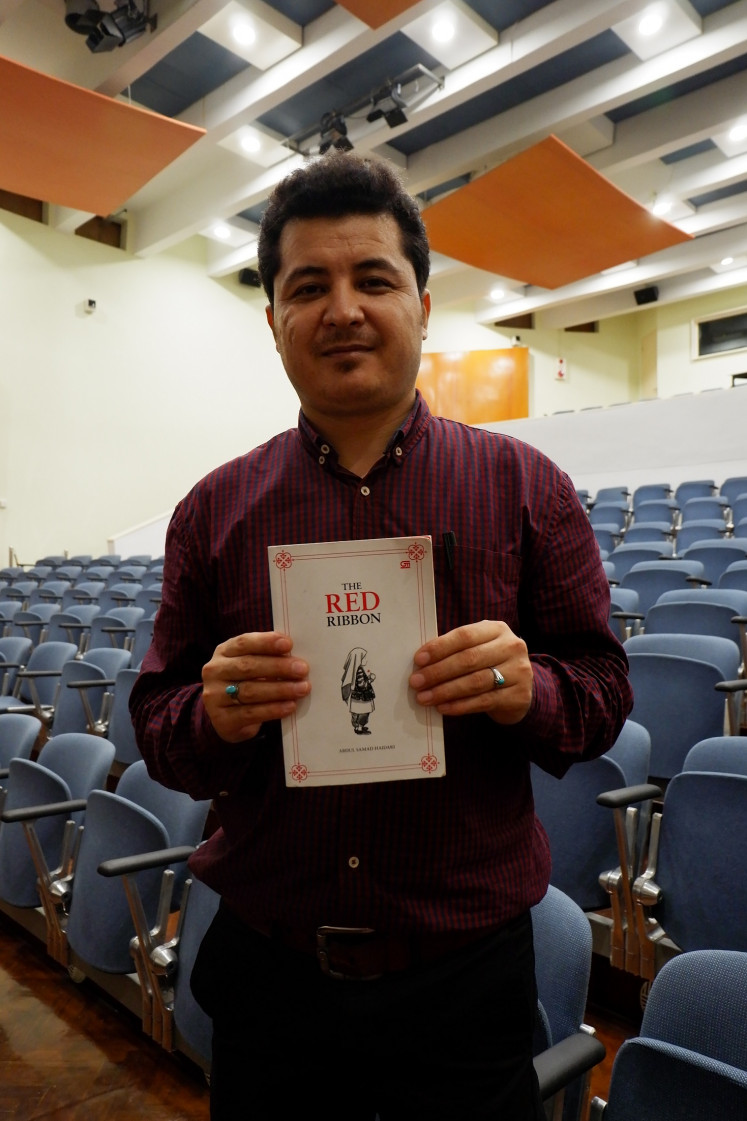

Abdul Samad Haidari. (JP/A. Kurniawan Ulung)The book, which took five years to make, explores his journey to seek peace from war-torn Afghanistan, where his ethnic group, the Hazara, still faces constant persecution.

“The name Red Ribbon is a tribute to my little sister, Hakima. I untied it from her gory hair as she was lying dead under the rubble of my bombed-out home. I took it as memorabilia of a stolen life,” Abdul said.

The Red Ribbon consists of 11 chapters that shed light on various topics, including the life of refugees at a camp in Kalideres in West Jakarta, the post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) that he experiences and the authoritarianism, terrorism and genocide that he witnessed in Afghanistan.

“I used to cut my palms and do other self-harm to divert the focus from the pain in the back of my head, especially when I was writing about traumatic events. I often cut myself to feel that I am really alive because I wanted to feel my existence,” he said.

Born in Dah Mardah-e Gulzar in Ghazni province 30 years ago, Abdul attributed his passion for writing to his father giving him pencils, notebooks and drawing books at an early age. His interest in studying literature continued to grow after he read two renowned poetry books, called Hafiz Shirazi and Panjb Kitab.

He said he had become a refugee at the age of seven after the Taliban attacked his house during a war. He fled to Iran but he was later detained by the Iranian authorities because he did not have any legal documents to travel. He was deported from Iran to Afghanistan three times.

On the second deportation, Abdul said, he was stopped in Kand-e-Pusht on his way to Kandahar in Afghanistan. He was taken off the bus along with three Hazara tribesmen.

The Taliban, he said, made him, along with his fellow tribesmen, stand in line. The Taliban shot the three but not him. Feeling pity, some Pashtun women saved his life. Abdul was put back on the bus.

They hid Abdul under a bus seat. He slept on the hot bus floor with some bags placed in front of him to make sure that the Taliban could not find him at other checkpoints on the way to Kandahar. Abdul passed all the valleys until he reached Kandahar and then went from Kandahar to Pakistan.

After the fall of the Taliban in 2007, Abdul returned to Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan and started his career as a journalist.

It turned out that Afghanistan remained unsafe. Abdul’s colleagues at The Daily Afghanistan Express were kidnapped after the newspaper published an opinion piece that the Afghan government considered blasphemous in 2014.

A year before that, his father and elder brother were kidnapped due to the newspaper’s stories and editorials about the Taliban’s war crimes, human rights violations and corruption inside the government.

After getting attacked, he sought asylum in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, but to no avail. He later found an agent who promised to take him to a safe destination. However, he was sold more than ten times.

“I did not choose the destination because I did not have the option to choose. The destination chose me. I had no control over my life until I ended up as a stateless refugee in Indonesia,” he said.

For Abdul, it was hard to believe that no NGOs were working on behalf of journalists and aid workers who had fled persecution and lived as stateless refugees with mental health issues.

He said dealing with PTSD was one of the biggest challenges he faced in writing about traumatic events in The Red Ribbon.

“I often fall over and cannot move or do anything. My body locks up, and the pain in the back of my head is very high all the time. Sometimes I feel like the sky is down and the earth is up,” he said.

Abdul thanked people in Indonesia for loving him and making him stronger, including his foster father, lecturer Ross Dunn, the spouse of New Zealand Ambassador to ASEAN Pam Dunn.

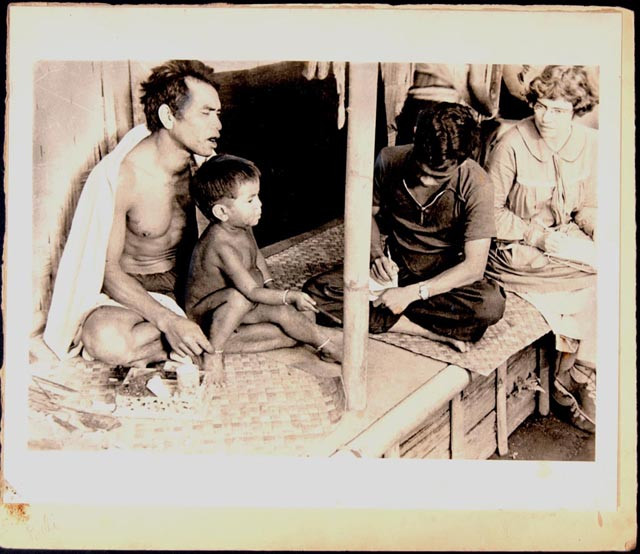

Abdul met Dunn through one of his students who visited the Bogor-based Jesuit Refugee Service Schools where Abdul had taught women refugees from five countries since 2015.

He said Dunn had lifted him up and had given him the courage to speak out and the vision to see life beyond the void.

“Ross Dunn is like the warm break of the early morning dawn, the glorious light of the new day whose light forms in me the resistance to defeat the dark-circled shadows,” he said.